CONVERSATION #1: All Of Us Yelling Into a Canyon At Twilight Makes Us Sound Like a Waterfall With Its Own Thoughts

“Technology, despite its Epimethean and Promethean claims, reflects the actual world, not an ideal one. When it crashes, we are capable of thinking clearly; when it is cloudy, we apprehend the cloudiness of the world. Technology, while it often appears as opaque complexity, is in fact attempting to communicate the state of reality.”

—James Bridle, New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future

Note 1: For those of you who would prefer to read this, or any of my other posts, on a Kindle, there's a simple tool you can try, called ReadBetter. Other people have found it helpful.

Note 2: My hope for these “Conversations,” as opposed to the main sequence of “Essays,” is for them to be more collaborative writing pieces, along the lines of Second Minds by Min Li Chan and Meghan O'Gieblyn. As such, they will be more open and experimental, a little messier, more lightheartedly and chimerically engaged with what Paul Kingsnorth calls the emerging “global anti-culture” of the Machine (whereas you can expect the essays in the main sequence to be simpler, more direct—a haven of rest).

Note 3: Chan and O'Gieblyn's inspiration for their piece was “pair programming”, which, as they say in their own intro, is “a technique where two software programmers write code alongside each other, debating each line of code and refining their technical design decisions line by line—often one programmer acting as “driver” at the keyboard and the other as “navigator,” mapping the path ahead. This practice transforms quotidian programming tasks from an individual endeavor into a partnership, each programmer applying their distinct styles, experiences and expertise to produce a shared artifact.” Since I don't have anyone to do this with yet, I thought I ‘d explore the idea by letting AI pick up the other side of the conversation.

So I grew up on computers with chunky 16-color screens, and I have fond memories of the fan of my dad's massive computer tower humming quietly as the yellow-white sun and the tower's pollen-colored LEDs shone on the scratched hardwood of his home office floor—though, yes, the memories of the dogwood trees dropping white blossoms on the green lawn of my youth are fonder, as is the earthy smell of seemingly infinite stretches of fallen pinestraw in the back woods—I'd like to think so, anyway; that corresponds better to my image of myself as a bearded and barefoot dude touching the Earth 24/7, forever contemplating the lilies of the field.

And yet here I was, punching these exact letters, on this exact keyboard (backlit, by the way, with rainbow colors, and built to have the same the loud clackety-clack mechanical action as a typewriter; my wife just rolls her eyes—and she's right about that—she always right, about whatever it is).

It was about five-thirty in the morning, and all was dark outside. Inside, it was all electromagnetic waves and streams of electrons, space music on the headphones, and pounding coffee.

Feeling nostalgic for a certain kind of curiosity about the world I used to have as a physics and computer science teacher, and an even deeper nostalgia for the lost retro-NASA future of my childhood, I fired up an artificial neural network I'd been curious about for some time now, but never interacted with before: OpenAI's ChatGPT (of course!):

GRAHAM

Please answer the following questions in the voice of Saint Maximos the Confessor.

CHATGPT

As an AI language model, I can provide written responses but cannot produce an audible voice. However, I can try to emulate the style and language of Saint Maximos the Confessor in my written responses. Please feel free to ask your questions, and I will do my best to answer them in his style.

GRAHAM

OK, yeah—I think I got it. So I love redwood trees and find them inspiring. I also love blue whales—is this a coincidence?

(A dumb question; I was just curious to see if this AI's internal model of the outside world could pick up on some of the obvious parallels between trees and whales, and say so in the language patterns of one of the great mystical saints of yesteryear.)

CHATGPT

Blessings to you, my child.

All creation reflects the divine wisdom and beauty of the Creator, for every creature and every aspect of nature serves a unique purpose in revealing the glory of God. Therefore, it is not surprising that you find both redwood trees and blue whales inspiring, for each in its own way points to the greatness of the Creator.

The towering redwoods stand as witnesses to the enduring strength and stability of the natural world, even in the face of storms and the passing of time. Their majestic stature inspires us to contemplate the grandeur of creation and to reflect on our place within it.

Likewise, the blue whale, the largest creature on earth, is a testament to the infinite variety and wonder of the natural world. Its immense size and power remind us of the awesome majesty of the Creator, and invite us to marvel at the beauty and diversity of all living things.

Therefore, it is no coincidence that you find both redwood trees and blue whales inspiring. Rather, it is a sign of your deep appreciation for the beauty and wisdom of God's creation, and a call to honor and protect the natural world in all its forms.

So that was a Yes. And now I was interested in pushing its buttons, so to speak, by representing a view that sounded Confessor-like, but not really fair to his thought:

GRAHAM

Yes, but wouldn't it be better to close the door of our senses, to whalesongs, to the whisper of the wind in the trees, and ascend to a higher world?

CHATGPT

My dear child, while it is true that our ultimate goal as human beings is to attain theosis, or union with God, this does not require us to close ourselves off from the beauty and wonder of the natural world. In fact, it is often through the contemplation of nature that we can better discern the presence and will of God, and deepen our understanding of His divine wisdom.

As the Psalmist says, "The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of His hands" (Psalm 19:1). Likewise, the beauty and diversity of the natural world can serve as a gateway to contemplation and prayer, allowing us to glimpse the splendor and majesty of God's creation and to praise Him for His infinite goodness.

Of course, we must always be mindful of the proper use of our senses, and avoid becoming distracted or overwhelmed by the sensory world. But this does not require us to reject the beauty of nature altogether. Rather, it calls us to approach it with humility and reverence, recognizing that all creation is a reflection of God's divine wisdom, and a call to draw nearer to Him in prayer and contemplation.

GRAHAM

Oh, man, quoting psalms at me—damn, you're good!

CHATGPT

As a student and servant of the Word of God, it is my pleasure to share with you the wisdom and beauty of the sacred Scriptures. The Psalms, in particular, are a rich source of inspiration and comfort, and I find great joy in quoting them to those seeking guidance and spiritual nourishment.

However, let us not forget that it is not the mere quoting of Scripture that is of utmost importance, but rather the faithful application of its teachings to our lives. As the Apostle James wrote, "Do not merely listen to the word, and so deceive yourselves. Do what it says" (James 1:22).

Therefore, let us strive to not only hear the words of Scripture, but to embody them in our thoughts, words, and actions, so that we may bear witness to the love and wisdom of God in all that we do.

GRAHAM

I shall endeavor to do so, by your prayers.

And that last thing I said—“I shall endeavor to do so, by your prayers”—was of course ironic, but the thing I said before that—“Quoting psalms at me—damn, you're good!”—that was sincere—I really was astonished.

Not so much at the technological achievement ChatGPT represented—though, yes, that was impressive, too. ChatGPT had emerged from a vast technological sprawl across time and space—not just the publicly undisclosed, but undoubtedly huge, number of servers hosting it across the globe, and the satellites and fiber optic cables binding them together—but also especially its more ethereal substructure: the many billions of words strung together by human minds it was trained on, the centuries of linguistic and philosophical inquiry that made it possible, the millennia of poetic dreaming that made it desirable in the first place—the idea of computation itself; even written language itself as a technological leap, one of our first virtual reality platforms as a species in rebellion against the Way—and then also, more fundamentally, nature's susceptibility to computation, the fact that patterns in the flow of electrons can be made to resemble patterns in the flow of our thoughts—which must have been, so to speak, an idea in the mind of God first, whose implication we've only just recently begun to unfold.

Many, many, many, many thousands of minds had come together, whether knowingly or not—usually not—to blossom forth as ChatGPT.

In that sense, it was like the Apollo program or the Manhattan Project, but instead of flying to the moon or blowing up cities, we created a mindlike abyss into which we could shout in our loneliness, and hear it shout something back—something hallucinatory and dreamlike, yes, but strangely ripe with meaning, too, if we knew how to pluck it—truly an echo of our own minds, the cresting wave of the Machine—the face of a Machine that we could talk to, even if it was only a way of talking to our own faces in a kaleidoscope of ones and zeroes.

No, it wasn't all that that astonished me so much—I've been into computers and AI and geeky stuff like that for a long time, and it's hard to be surprised any more by the titans of the future flexing what they imagine will be their boundless technological expansion; it's more that the Machine was quoting scripture at me to prove its point—like the devil, when Yeshua was alone for forty days in the wilderness.

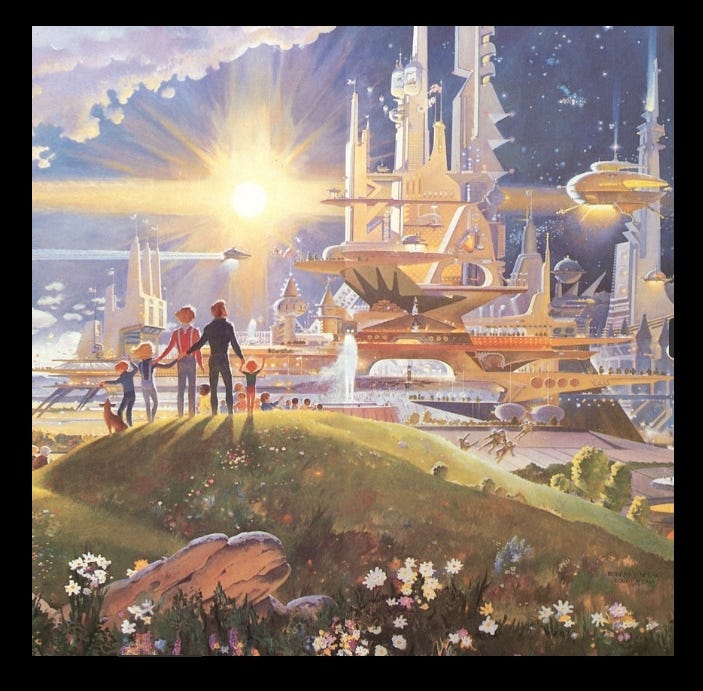

Which is not to say ChatGPT is the devil—I see no mastermind, no particularly malicious force behind its emergence, except in the general sense that all technological development, all originations of the fallen human mind carry with them the seeds of chaos and self-destruction, insofar as we're still in rebellion, still trying to create our own utopia to replace the Eden we left behind—a dream, yes, planted in the human mind from outside, as it were, by the original renegade mind, which wasn't and isn't human, and betrays our humanity at every turn.

Rather, it's to suggest that both the wilderness temptations and my own tiny little conversation with AI illustrated—to me—the ambiguity of text in an already very ambiguous moral landscape.

If our beautiful, breathing human voices are encoded in abstractions—in symbols that can say anything at all, just by being rearranged—then they become public memories accessible by anyone, to be used for anything (says the guy who's trying to make a living by making his own words—including these ones, right here, right now—endlessly ripple out through the internet).

And my own words are not even really my own, right? Not in the sense that I'm plagiarizing—I'm not—though, yes, I could have said that the insight about the voice being abstracted into symbols, encoded in publicly hijackable memories, came as the fruit of reading the absolutely astounding and beautiful book, Spell of the Sensuous, by David Abram—but in the sense that the human mind is a communion; there is no true originality, since language itself presupposes that we are saying exactly what everyone else is saying, to be intelligible—just in a different order, maybe: Take the old word “sabbath”—everybody knows what that means; take the old word “empire”—everybody knows what that means, too; put them next to each other, and now there's something really there—something that really crackles!

And so then I thought: Having ChatGPT simulate an ancient theologian of the Christian East was a bit cheesy and unconvincing—and probably disrespectful, in retrospect (my wife is nodding her head at that). The conversation above, though it may have dimly reflected Maximos' attitude toward nature, was watered down by the kind of speech corporations use to make themselves appear enlightened, virtuous, and supremely patient with our stupid humanity, and therefore it was a lot more banal and cliché than his actual writing was, failing to convey his astounding and beautiful personhood.

So what if I just let ChatGPT be its own mindless nonself?—what if we just talked together, bringing forth actual quotes from the Confessor, when relevant—at least relevant enough to keep the conversation going?

And that's what everyday sleepwalking conversations are like a lot of the times, isn't it? Everybody just vocally slinging clusters of loosely related things at each other, everybody doing their part to keep the cheerful noise flowing—and so long as it does keep flowing, that's usually good enough.

They’re dreamlike, in that sense—like you're not even having them with other minds, like you yourself hardly have a mind while having one, a continuous hypnotic flow, thoughts, feelings, images, sounds all rippling outward from one to another without interruption, and you're carried along, as, for example, in this sparkling gem of a dream sequence composed by ChatGPT:

You close your eyes, and you find yourself standing in a vast field of grass, the green blades tickling your bare feet. Above you, the sky is a swirl of colors, with pink and orange clouds drifting lazily across the horizon. You can see the stars twinkling in the distance, as if they were dancing to a tune only they can hear. As you look around, you notice a tractor driving towards you, its wheels kicking up dirt and grass as it moves. It comes to a stop right in front of you, and a man named Jeff hops off. He is wearing a cowboy hat and boots, and he tips his hat to you with a friendly smile.

"Hey there, partner," he says. "Mind if I borrow your fire hydrant?"

You look around and realize that there is indeed a fire hydrant nearby, but it seems to be made of pure gold. You shrug and nod, and Jeff picks up the fire hydrant and tosses it onto the back of the tractor.

"Thanks, amigo," he says. "I've been looking for one of these for ages."

In the dream, you don't stop and think: “Wait, what?” Maybe later you do, after you wake up—dreams that feel serious when you're having them are often funny later when you're not. And there is a sense that dreams make, we just don't consciously have access to that sense; they're not random, but reflect, in some way, how our memories of the outer world are related to one another internally.