“I live not in dreams but in contemplation of a reality that is perhaps the future.”

― Rainer Maria Rilke

So this is how I ended my recent book, Sunlilies: Eastern Orthodoxy as a Radical Counterculture:

In bringing these essays to a close, let's imagine Orthodoxy together as a kind of quietly subversive, radical “Sabbath empire” of Ethiopian-style forest churches bearing witness to the Eden from which we all came, and to the Eden to which we are all meant to return, by God's redemptive power—a world of green plants and blue skies and earthborn, Earth-loving men and women under the yellow sun, where all things, men and women, boys and girls, trees and birds, sun and moon and stars, trickling brooks and soaring white mountains of clouds, sparkling blue seas and leaping blue whales and gleaming tribes of silver dolphins, and clouds of iridescent dragonflies and sapphire-armored bluebottle flies, and sun-lilies and asphodels and yellow goldenrod flowers and fragrant nectarine trees, receive their lives directly from the breath of God, and freely offer their lives to God and one another, a vast communion of love giving thanks with their whole lives to the Father of all things. This is the future—the Messianic Age—which Yeshua, the “Last Adam,” has allowed us to begin realizing even now, celebrating it with our communal feasting, despite the bleakness of our times; this is the bright future to which his Eucharist points, and in which it already participates every seventh day, the day of the Sun...

How lovely, if I do say so myself! And this is indeed the future to which this Substack's subtitle, Visions of the Future From the Wilds of Eastern Christianity, refers—but I fear such a future may seem overly romantic and irretrievably remote.

I mean, look at the world we're perishing in: What used to be the richest man in the world recently expressed his desire to build a space station above the Earth, so people like him can fly up there and have a good time—and yet, the other day, I encountered a brown-eyed, brown-haired homeless indigenous man at the top of the exit ramp holding a piece of cardboard that said:

ANYTHING HELPS

What he meant was: A quarter, a nickel, a dime, half a sandwich—whatever you can offer as you wait for the light to change—even the smallest gift will help me stay alive another day—but what he should have written on his cardboard sign was:

HAVING OUR LAND BACK HELPS

—for it is only because his ancestors had been torn up by the roots from their home on Earth that he himself was still adrift, lost, barely able to survive, much less flourish, generations later.

Space machines in the sky, grinding poverty down below—of course, they're not unrelated. Like a small, white cloud and its drifting shadow, one is only possible because of the other, as two expressions of the same thing: Only a civilization of one-eyed utopian dreamers—who have come to see Earth and also themselves and especially other people as only so many well-functioning machines, and Creation as only so many raw materials to be extracted and commodified—is capable of the kind of large-scale, organized destruction of nature, both human and wild, which feeds the economic, technological, and political systems making the construction of spacecraft possible.

Only such a civilization would have wanted to leave Earth in the first place.

This self-destructive, all-too-human civilization has been called by many poets and philosophers, especially Paul Kingsnorth of late, simply, “the Machine.” Its underlying culture is very, very old—as old as humanity itself—but since its growth is exponential, it seems to have come out of nowhere in the last several hundred years, and especially in the last hundred—and even more so in the last thirty, particularly the last five.

We experience it now in many facets—as an Earth-devouring globalized hyper-capitalism; as a glittering constellation of multinational corporate fiefdoms; as the omnipotence and omnipresence and omni-surveillance of the military-industrial-academic-media complex; as the digitization and virtualization of nearly everything that was once irreducibly real, especially human freedom and human love—but these are only superficial manifestations of their underlying core, which will still very much be here when all these things have morphed beyond recognition.

That core is in the fallen human heart. As Kingsnorth, the great Orthodox poet-gardener of our times, says in his essay, The Migration of the Holy:

The Machine is a material manifestation of an internal human desire for 'liberation', in which all forms are dissolved in favor of the final and only sovereign: the independent rational individual, freed from the obligations of history, community, and nature.

In other words, the Machine springs from a very human desire for transcendence—a thirst given us by God, a thirst we are very much meant to quench. As another poet-gardener, Wendell Berry, says likewise in his essay The Use of Energy:

The knowledge that purports to be leading us to transcendence of our limits has been with us a long time. It drives by offering material means of fulfilling a spiritual, and therefore materially unappeasable, craving: we would all very much like to be immortal, infallible, free of doubt, at rest. It is because this need is so large, and so different in kind from all material means, that the knowledge of transcendence—our entire history of scientific “miracles”—is so tentative, fragmentary, and grotesque. Though there are undoubtedly mechanical limits, because there are human limits, there is no mechanical restraint. The only logic of the Machine is to get bigger and more elaborate. In the absence of moral restraint—and we have never imposed adequate moral restraint on our use of machines—the Machine is out of control by definition...[Our] crisis reduces to a single question....Can we, believing in the “effectiveness of power,” see “the disproportionately greater effectiveness of abstaining from its use?”

Our craving for transcendence—for deathlessness, eternal clarity of vision, perfect rest—is, Berry says, “materially unappeasable”—it springs from our infinite interior spaces, from the human spirit in relation to the Eternal Spirit of God, and cannot be satisfied by the invention of new tools and techniques for controlling nature, though we are endlessly hallucinating the possibility that it might. Scientific utopia, lying forever just beyond the horizon, is the collective daydream which propels the Machine ever onward and upward, laying waste to Earth despite our best intentions.

In a way, the dreamtime 'fall of man' in the Hebraic vision of the bible can be read as a story about the Machine's inception, the moment we transferred the longing of our hearts from Eden's flourishing, humane wildness to a utopian dreamscape which had suddenly come to exist in the collective mind's eye. The Orthodox poet-theologian, Philip Sherrard, describes this as a tragic 'shift of consciousness' in his essay, A Single Unified Science:

The fall may be best understood not as a moral deviation nor as a descent into a carnal state, but as a drama of knowledge, as a dislocation and degradation of our consciousness, a lapse of our perceptive and cognitive powers—a lapse which cuts us off from the presence and awareness of other superior worlds and imprisons us in the fatality of our solitary existence in this world.

If, in the dawn of human life, we saw Creation as the Body of God, the serene and harmonious flourishing of an overwhelmingly beautiful, inexhaustible plenitude of lifeforms—all interconnected, all revealing God's inner life, a vast communion of love—then after this fall in consciousness, we saw it only as a chaotic swirl of elements and forces—a hostile, impersonal, ineffable machine, inside of which we had suddenly awakened to ourselves as naked orphans.

From then on, salvation was to be found in the construction of an alternative, artificial, supposedly more human-friendly world than the one God made: the city, the seed of our emerging technocratic dreamscape.

In the spiritual chronology of the Hebrews, the archetypal city is Babylon—the first serious manifestation of the Machine against which they contended. Situated in the early days of the experiment of civilization, Babylon is synonymous in Hebraic thought with what we might call the scientific control of nature: In a world of baking hot sun, and of two capricious rivers—the Tigris and the Euphrates—which were as likely to sweep your village away in a cataclysmic flood, as they were to leave it suddenly stranded in the desert, to die slowly of thirst and famine—here was a massive citadel in which the forces of nature had finally been subdued by its great kings: Giant canals and a circuitboard-like system of irrigation ditches regulated the flow of water to plots of land in which genetically modified grasses (wheat, barley, and so on) were planted in rows and columns; massive walls ringing the city protected its vast interior stretches of perfectly level ground, across which humans could walk from from point A to point B in a straight line, encountering neither plant nor animal, nor undue sun or wind; and, most spectacularly of all, out of the shifting mud and sand arose an artificial, highly “pixelated” mountain, perfectly shaped—the central ziggurat—called pejoratively in the bible the Tower of Confusion (babel).

Consonant with these feats of engineering, and only slightly more hidden, were the achievements of the Babylonian “soft sciences”: its organization of large-scale human society into what the philosopher Lewis Mumford calls “the archetypal human machine,” able to construct canals, walls, and ziggurats where none had existed before, its use of liturgy as a tool of social and political control, programming the masses to see and especially to feel that the king on his throne, and the hierarchy of relationships spreading out beneath him, were the fountain from which the order of the entire cosmos flows, and so on.

What Genesis speaks about in seemingly metaphorical language—the separation of water from dry land, the appearance of solid ground where there had once only been a formless waste— had quite literally happened in ancient Mesopotamia at the command of the visionary kings of Babylon.

From this perspective, what nature is for is to be flattened, geometrized, and controlled—a vast “sandbox” in which to construct a world responsive to human desire—and only human desire, not that of any other living creature, or of God. Nature, in this reading of Babylon, is not the living image of God, nor is it a participation in the harmonious, self-giving life of the divine communion; rather, it is an arena of inert, impersonal atoms, against which man can flex his godlike powers.

In the story of the fall of man in Genesis 3, the “serpent” persuades Adam and Eve to eat of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. Since the serpent's punishment for doing this is the loss of its legs (Gen. 3:14), we should not think of it as something similar to an anaconda or an emerald boa, but perhaps specifically the Babylonian mushhushshu, or “furious snake”:

The mushhushshu was a totem of Marduk, the high god of Babylon. Since a god, among other things, is an image which crystallizes a people's vision of life, and around which they organize and amplify their vital forces as a community, the story of the mushhushshu in Genesis causing Adam and Eve to betray one another, and also their Creator, and also the garden-like Earth which was their home, is a story about Babylon betraying the Hebraic sense of life, the Creator, and the Earth itself.

Secondly, what was the source of the “forbidden fruit”?

Since, for the Hebrews, “good” and “evil” were not only ethical qualities, but had cosmic dimensions, too, I prefer the “Tree of the Knowledge of Order and Chaos,” over the more conventional “Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil.” In Genesis 1, God calls each of his non-human creations “good”—light, sky, sea, sun, moon, stars, plants, animals, et cetera—even though they lack “ethical” content as such, since they face no moral choices. What is “good” about them is their beautiful, harmonious order, revealing the harmonious life of God—as opposed to the “chaos and waste” which preceded them (v. 2). On the other hand, an ethically “good” person is just one who has well-ordered relationships with him or herself and others—nothing more, but also nothing less.

Similarly, when God says in Isaiah 45:7, “I form light and create darkness / I make shalom and create calamity [='evil' in the KJV],” he is talking about what we would call natural disasters—earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, windstorms, floods, et cetera—which are experienced by humans as painful disruptions in the local order of nature, and thus “evil” in the Hebraic sense, though they are ethically neutral, since volcanoes do not “choose” to erupt, and so on—and though, at a scale greater than that of an individual human life, they are an expression of God's creative order, after all: New islands come into existence because of volcanic eruptions, the flow of temperature and pressure, without which life could not exist, is also the source of destructive windstorms, and so on—which is why God can be said to be the source of calamity in Isaiah 45, without thereby intending to describe him as either malicious or capricious.

From this perspective, the Knowledge of Order and Chaos is what we would call “science” today—not in the sense of a pure, childlike wonder about how nature works and a commitment to observing it closely (this kind of “science” has largely vanished, from what I can tell, and is not generally what we mean by the word), but in the sense of the driving force of technological expansion. This includes not just the creation of new tools amplifying the power of the human body over its environment, but also the development of new techniques of control: Psychology and economics, as much as physics and engineering, are “science” to us now, since they are helping build the world of the future, a utopia of machines in which all things on heaven and Earth will have been made to responsive to permanently adolescent human desires.

Thus, Genesis is, in part, a record of a tragic shift in consciousness from seeing nature as the body of God, transforming his inner life as a communion of love into the outer life of harmony in all things, to seeing it instead as the visionaries of Babylon saw it: an hostile, impersonal arena in which to expand human control until we realize utopia—until, that is to say, nature has become a mechanical body, transforming our inner void as calculating egos into an outward, derelict rationality of all things.

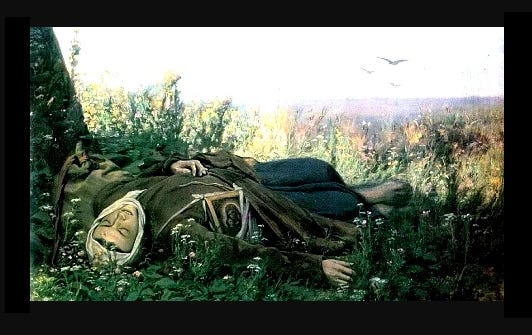

But this also means Genesis can be read, in part, as a record of the Hebrews as the first intentional counterculture against the Machine. In Genesis 2, the Hebrews creatively remember themselves as a people radically divested of all technology—even the most basic and “necessary” of human technologies, that of clothing. Adam and Eve (primordial children of God, thus primordial Hebrews) are naked and unafraid in Eden before the fall—without tools, without math, without construction projects, without religion, without kings.

Serenely empty of all such artifice, they are full of the presence of God, who goes “to and fro in the garden in the wind of the day” (Gen. 3:8). And they are full of the presence of all the animals, too, to whom Adam gives names (2:19)—that is to say, he recognizes them deeply, sees their origins and their destinies, calls them out of nothingness into the fullness of life as a vast communion with his godlike power of speech. And they are full of vitality in their vocation as peaceful gardeners, having been given “rest in the Garden of Eden in order to cultivate and watch over it” (2:15).

There was only one “law” in this long-ago mystical anarchy: To be watchful and to resist:

Adonai Elohim commanded the man saying, “From all the trees of the garden you are most welcome to eat. But the Tree of the Knowledge of Order and Chaos you must not eat. For when you eat from it, you most assuredly will die.” (2:16-17)

But why is such fatal knowledge portrayed as coming from a “tree” as such? Why not some more obviously unnatural source, like 2001: A Space Odyssey's black monolith—touch this, and you'll die, but stay up in the trees where you belong, and all will be well?

What I hear this saying is that the scientific consciousness grows naturally from Earth's cycles of birth, growth, and decay—a natural, and even inevitable, fruit of the mind.

Even so, it can be accepted or resisted, and God's life-giving command in the beginning was, above all, to watch and resist. Ascetic denial of that which arises blamelessly in the animal mind (which desires security above all), was to be humanity's preparation for one day eating of the Tree of Life—that is, for partaking of the endless life of God—who, as always self-emptying for the sake of love, desires no security whatsoever.

This was to be a slow, patient, naturally unfolding process: Day by day, Adam was to learn to freely resist what would become the Babylonian daydream—the scientific flattening of nature, reshaping it for the sake of the human will alone—and to freely embrace the reality of Eden instead: a roaring waterfall of living beings, infinitely diverse, all living in and for and as one another, a vast communion giving voice to the boundless, self-giving life of God.

Both parties—man and his Creator alike—needed to learn to trust one another through a long experience together in the world, in which the absolute freedom of both sides was respected. If man could learn to freely impose limits upon his own godlike power to reshape Creation—despite all the many scintillating utopias waiting for him just beyond the horizon—then he could be trusted to live forever; if not, then he would have to fall apart, as a severe mercy to all the little beasts—both human and wild—whom he might irrevocably destroy with his power, probably without even realizing it.

This is true for at a personal, existential level—but it is also true at the level of whole civilizations as well: If you “eat” this shift in consciousness (in other words, if you deeply internalize it), it will be the end of you—you will feel lost, adrift in an uncaring universe, you will fight tooth-and-nail against other precious human beings for resources, you will self-isolate in a hell of thoughts, you will quite literally tear your own life apart grasping for who-knows-what. This is what we have been doing as individual people, and also as vast constellations of people, for quite some time now—though not forever. This self-destruction mercifully ends at death: in the hour of our personal death (or, sooner, in the voluntary “death” of following Messiah's way of life), and in the inevitable collapse of civilizations who live this way.

We desire transcendence, and this desire is real—it is a thirst for water which really does exist—but since it is so intense, if misdirected it can mindlessly destroy that which it wishes would live forever.

The Machine, in its early form as Babylon, drove hard to construct a paradise of well-ordered men and women living in peace among terraced, irrigated gardens, but this dream has literally turned to dust—it's all just horizon-to-horizon desert now—a desert made by man. Jeff Bezos, always in his own mind making the world a better place, will no doubt build his Orbital Reef space station, and all of us wandering orphans of Earth will no doubt lose ourselves more and more beneath its shadow. Then he himself will turn to dust (as I will, also), having done his part to re-create the world in the image of the Machine.

Bezos, Kurzweil, Musk, Gates, and so on—all the starry-eyed technophiliacs of our time—they only want what all of us want: deathlessness, clarity of vision, perfect rest. But we should not, therefore, imagine them as the vanguard of human transcendence. They will not ultimately get what they want, and they will not get us what we want, either, though this has been the implicit promise undergirding their very expensive—in terms of human suffering—bridges to nowhere. They, and their machines, will slowly go the way of the buffalo, as all such utopian dreamlike nothingnesses eventually do.

There is another way, a way towards the bright future described at the top of the essay: Going deeper into Earth, rather than trying to escape it—a rooted transcendence, in the place of runaway visions of machine paradise—a Sabbath rest which puts an end to all utopian hustle.

This is a way of life coming down from the Creator of life himself, which is why the Machine trying to extinguish it will never triumph. In saying this, I wish to express my affinity with, and appreciation for, the sun-like confidence of D.H. Lawrence, as expressed in his poem, The Triumph of the Machine:

They talk of the triumph of the machine,

but the machine will never triumph.

Out of the thousands and thousands of centuries of man,

the unrolling ferns, white tongues of the acanthus lapping

at the sun,

for one sad century

machines have triumphed, rolled us hither and thither,

shaking the lark's nest till the eggs have broken...

Hard, hard on earth the machines are rolling,

but through some hearts they will never roll...

And against this inward revolt of the native creatures of the soul

mechanical man, in triumph seated upon the seat of his machine,

will be powerless, for no engine can reach into the marshes and

depths of a man...For me, such confidence comes from my own experience with nature, and with the spiritual mothers and fathers of Eastern Christianity who have gone more deeply into nature than most—certainly more deeply than the technocrats trying to out-engineer Creation with their global mesh of machines.

The “rooted transcendence” the saints of Orthodoxy espouse—which is a life of lily-like Sabbath rest, blossoming into the eternal (but still very human, very earthy) deathlessness of Messiah—is not quietism. It is not merely a withdrawal from history, let the world be damned. Rather, it is an active engagement with history and the world, an active and energetic and creative, beautiful way of life, albeit scarcely recognizable as anything at all, at first, to the Machine's true believers.

It is, so to speak, a hidden Sabbath empire, growing like lilies through the cracks of the world system's concrete.

In this new writing project, I will explore various facets of this hidden way of life, describing in fresh language for our times how it can carry us through not only the apparent triumph of the Machine, but also the fiery throes of the Machine's inevitable self-destruction. You will hear about wild saints and forest-gardens, and about the depths of the heart; you will hear about a new vision of science, about the anarchic desert fathers, and flowerlike machines—we’ll explore many things together. It will be quite an adventure!

As in my book Sunlilies, I will present a basically childlike view, without apology; at times, I will act as if almost the entire intellectual history of the West never happened—as if it were a mere nothing, “a chasing after the wind,” to quote the philosopher-king of Ecclesiastes (1:14). This is because, on the one hand, recursive self-scrutiny is a downward spiral that goes nowhere. On the other hand, childlike surrender to the great I AM, to the “the Way, the Truth, the Life” leaps over every impasse and produces its own results—regardless of so-called logic, regardless of so-called history.

This has been your introduction in terms of words and sentences in the mind. The real introduction, though, would like take place in terms of the postures of the body and awareness of its beautifully mind-surpassing tangle of roots in all living things. Let's “look closely at the lilies of the field” (Mt. 6:28) and become like them, as Yeshua suggests—those little flowers in whom Yeshua delights, who egolessly drink the sun.

Theirs is a history of the body rather than that of the mind: For them there never has been, nor ever will be, an Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, Newton, or Descartes—and they have never needed one, and nor have we.

For a moment, let's stop trying to figure out what went wrong with everything, and go outside into the sun—it's still there. As in, upon completion of this essay, let's put the screen down or turn it off and really get up and go. Let's find a tree or a rock or a little pond or even a stray blade of grass pushing up through the asphalt of the roof of the apartment complex, and sit comfortably beside it—it's still there.

Let's take a few very long, slow, deep breaths through the nostrils, exhaling very slowly each time—we're still there. And then let's say, “Lord Yeshua Messiah, son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner”—he's still there, too. And he's all we really need.

love,

graham

I'm so glad I found your work via Paul Kingsnorth! It feels like the right time and place for this. I look forward to following you on this journey and being inspired by your work. I desire to disengage from the machine while faithfully stewarding my family. Suffering is okay and expected, but I've got to make sure it is done with careful intention.

My first thoughts go to the city we all live in, wherever that place may be, and then how it resembles Babylon...and then how we can change it. But looking outward to find things to change (or really, critique), seems foolish when I consider the power I already have to change my surround. And then that seems foolish when I consider what needs to change within me. Everything is created in our image, but unless and until I can find the way back to the likeness of God in my own heart, the things I change outside will reflect the distortions unchanged within. I see a dual process, however, in my life. Changing the obvious affronts to peace and beauty in my surroundings at home and in my relationships while simultaneously targeting the chaos and disorder within. Both evolve as a process. As I change, traveling back "to that ancient beauty of Thy likeness," as the Orthodox death hymn states, my micro world at home should take on more of that image of Eden that the machine has marred.