Jesus does not seem to have had a vision of a triumphant and triumphal church encircling the globe. He always depicts for us a secret force that modifies things from within, that acts spiritually, that shows us community, unable to be anything else but community...The concept “Christian,” then, bears an inverse relation to numbers, whereas that of the State bears a direct relation. Nevertheless, the two concepts have been combined, to the great advantage of nonsense and the priests....People cannot see or understand that Christianity has been abolished by its propagation.

– Jacques Ellul, The Subversion of Christianity

I. THE EPHEMERAL HONEYMOON

Next to the road grow many flowers. I nod to them as I go by. They talk in shadows. And this I have learned: Grownups do not know the language of shadows.

– diary of Opal Whiteley

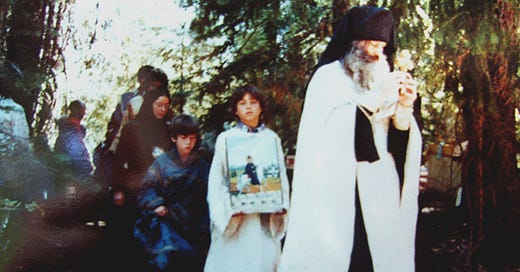

Twelve years ago, my wife and I—as newlyweds and new converts to Orthodoxy both—left the little cabin in the redwood forest where we were honeymooning in northern California, to make a pilgrimage to the resting place of Father Seraphim Rose—to the monastery he'd founded on a remote mountainside (pictured above) back in the late 1960s, fleeing the burning ship of American nihilism.

The drive there was beautiful, half of it along the dark and jagged coast, slackjawed at the gargantuan trees constantly appearing and disappearing and reappearing again from within the blue-white clouds coming up from the lapis lazuli sea, the other half on winding roads through the dust mountains, where, when stopped to have a picnic lunch, we realized the scraggly yellow wildflowers everywhere on the slopes—more or less sepia in colortone from hot sun and dust, but also from the nostalgic, photogenic, almost seraphic haze of dreaming about what might lay ahead at the monastery—were as tall as we were; taller, in fact—which seems like a metaphor for something, I know not what.

And when we finally arrived, we parked the car in the sand and dust, surrounded by soaring pines.

We sat there in the silence of its dusty dashboard, the engine ticking off its summer heat, then got out of the car, looked around: Pine trees, dusty rocks, sand, pine needles, a few stuccoed buildings, and the smell of hot sunlight coming off the bark of the trees.

We waited for awhile again—I guess we thought something was supposed to happen, but nothing ever did.

So we walked through the monastery gate, then up slope a bit, to Father Seraphim's grave (it was easy to find), to mumble some prayers and wait some more, wondering if all this was OK, to make ourselves at home, and suddenly some Russian babushka came bustling out of nowhere—out of the protean shadows of the trees or something—and told my wife she had better put a headscarf on: This was a monastery, wasn't it?

Then she looked askance at me and grunted her approval—for the time being.

I was elated!

Indeed, I was reppin' the American Orthodox look pretty hard in those days, as of course I still am today—good beard, long hair tied back in a man-bun, shoes made of hemp, red flannel shirt, nerd glasses: Reason enough to become Orthodox, in my book.

Sonia put a headscarf on. If that was some cultural kind of thing about modesty, it backfired—she immediately looked a thousand times more beautiful than ever, and I felt bad for the monks, who had their work cut out for them. But I felt pretty good for myself, with this very beautifully Old World-looking American gentle-souled hippie wife of mine—reason enough to stay Orthodox, I was to learn over and over again, over the next twelve years.

Anyway, once our little cultural situation was corrected—or, in my case, continued to be correct, to my delight—the babushka calmed down and was rather pleasant with us. She explained how to find, and how to greet, the abbot; she explained when the next divine service was, and how to stand in the temple, and where the outhouses were; in short, she had swooped down us like a mother hen, and was sheltering us under the wings of some very specific directions—the slow and only way to learn a culture.

But one thing she said to us just didn't register at all; at the time, I had no idea why she said it.

In fact, twelve years on, I realize it's sunk into me quite deeply, like a thorn—or, rather, like a seed blossoming into some other kind of world than the tiny, tiny, tiny one I was in when she first said it.

Again, this woman was a Russian—a Russian Russian, not a Russian American—she'd flown from Russia to California only a few days before, and was here only to visit and go back, not to live.

A Russian—someone who remembered what life had been like under the godless Soviets, someone who remembered—at least from stories told by those who knew them, or at least people who knew people who knew them—the holy Orthodox martyrs of the Communist yoke; a child of longlost Holy Rus'; a grandchild of the Orthodox world's most legendary monasteries—Valaam, Optina, Novospassky—now flowering again in the sunshine of a newly post-Communist spiritual-slash-political rebirth.

This Russian Orthodox woman from Russia—who, as I say, was very, very Russian—stopped giving us instructions for a moment, looked around at the pine trees, swaying as they do in their stereotypical wind, and at the rust-colored pine needles beneath them, at the sunbleached depths of the forest, at the crappy little monks' shacks dotting this anachronistic Shangri-La in the mountains of California, then looked at me and said: “You know: When I want to come to a real monastery, I come here.”

Wait, what?!

Girl, don't say stuff like that—it's confusing!

Confusing to someone like me, who at the time, was a proto-OrthoBro before it was cool, whose dream of Orthodoxy was so shaped by Dostoevsky, so enamored of the Holy Russia of yesteryear, that the first time I tried to visit an Orthodox church (with my dear friend Henry, previously mentioned), I literally could not find the building, because, in my mind, I was looking for the luminous, blinding sunlike golden effulgence of a gloriously beaming tsarist onion dome (it turned out the church was in a strip mall).

How could an American Orthodox monastery—founded by an American who really was an American—just some Californian ex-Beatnik dude, albeit a brilliant one, the son of American Protestants, desperately thirsty for signs of life in the spiritual wastelands of America, not one of Russia's many holy émigrés, who kind of unfairly stack the charts of American saints, in my opinion—be more real than the Russian Orthodox monasteries back home in Moscow?

I was a barely-Orthodox fawn in the headlights of my own stupid protest against Protestantism at the time; I didn't have enough context to ask the question; I scarcely do now!

But I tell this story as a kind of Zen koan to myself, a tiny gateway through which I can slip away from the complexities of an Orthodox world that's become far, far too vast for me:

What is the sound of one hand clapping?

How, under a shadowless tree, are all people in the same boat?

If the moon already set at midnight, why do you walk alone in the marketplace of the city?

And if a Russian Orthodox woman leaves Russia in search of Russian Orthodoxy, where are we right now, and what time is it?

II. THE ETERNAL WAR

It is not possible for Christians to have a Church

And not to have an empire.

– Antony IV, Patriarch of Constantinople

And Athanasius, wily, on the run,

a glamorous bandit, sending in his thugs

to rile up orthodox riot...

– Maryann Corbett, Creed

To be honest, I don't really know where we are, or what time it is:

Is Patriarch Bartholomew the patriarch of Constantinople and therefore the so-called Ecumenical Patriarch (EP) and leader of the world's 300 million Orthodox Christians?

Or is the EP actually a schismatic, heretical, power-hungry and delusional neo-papist relic of the past cordoned off in the Phanar district of Istanbul, not “Constantinople,” since Constantinople has long since gone the way of the buffalo, along with the Byzantine Empire whose capital it hasn't been for a long, long time, and the administrative head of possibly 5 million Orthodox worldwide, only 5,000 of whom actually live in the same country as he does, about 150 of whom might join him for the Divine Liturgy on a given Sunday?

And is Patriarch Bartholomew “among the world’s foremost apostles of love, peace and reconciliation, and justice for humanity and all of creation”? (That's what the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America says about him.)

Or is he rather “an enemy of the Triune God and our Mother of God because he maintains an institutional friendship with conscious and unrepentant heretics and heterodox”? (That's what Elder Gabriel of Mount Athos says about him—and apparently plenty of other Athonite monks would echo the same).

And did the EP, in creating the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU) from the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Kiev Patriarchate (UOC-KP) and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC), as over and against the much more populous and also apparently much more canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (called by some Moscow Patriarchate (UOC – MP), but actually fully autonomous), heal a lamentable schism and return the Ukrainian Orthodox to the freedom from Moscow they'd enjoyed for centuries prior to Moscow's conquest of Kiev in 1686?

Or did he literally “team up with former Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko and the U.S. State Department to invade Ukrainian Church territory, enter into communion with anathematized schismatics, and create a competing ecclesiastical structure on the territory of the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church”—which, by the way, is now suffering “brutal persecution by the Ukrainian government”?

And speaking of the EP and the UOC-MP, did the current Russian Orthodox Church (ROC), led by a KGB spy, actually come into existence only as recently as 1945, at the behest of Stalin and the KGB, rightly avoided, says the Russian True Orthodox Church (RTOC), as the “false sergianist church of the Sovietized Moscow Patriarchate” that it supposedly still is today?

Or do the words of Father Andrei Psarev—praising the reunion in 2007 between the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) and the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR)—“we have no other Church, nor do we have any other Russia” reflect the heart of most others in ROCOR, too?

Meaning, the MP's ROC—that's the OG Russian Orthodoxy, not just some statist edifice of the KGB? And there is no other?

Or does the fact that even ROCOR, of all churches—once known as the most badass, the most steadfastly faithful to the real Russian Orthodoxy almost entirely swallowed forever up in the abyss of 1917—has now, in the words of the Russian Orthodox Autonomous Church (ROAC) “finally capitulated to the only fully intact remnant of the Soviet regime— the Moscow Patriarchate” mean that the “Satan-led and fetid pan-heresy of Ecumenism” is truly everywhere now, and that these really must be the Last Days, since the spirit of ecumenism, “the last temptation of history,” the “Great Temptation of the End Times” must necessarily usher in the reign of the Antichrist?

And, anyway, about this Church, and about this Russia, whichever one we're talking about: Is it true that “the spirit of the Antichrist operates in the leader of Russia, the signs of which the Scriptures reveal to us: pride, devotion to evil, ruthlessness, false religiosity?” (That's what Metropolitan Epiphanius I of Kyiv said about him).

Or is Vladimir Putin, rather, a “miracle of God,” leading Russia's fight as the last “restraining force” against the Antichrist, delaying his arrival on behalf of the rest of the Orthodox world? (That's what Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Rus' said about him).

Or is he neither, actually—just a man “drunk on power” in the normal way of things, who imagines himself, as many people have before, as “the emperor of our times” (That's what Patriarch Theodore II of Alexandria said about him—which sounds pretty grounded at first, but then again, the man's full title is His Divine Beatitude the Pope and Patriarch of the Great City of Alexandria, Libya, Pentapolis, Ethiopia, All Egypt and All Africa, Father of Fathers, Pastor of Pastors, Prelate of Prelates, the Thirteenth of the Apostles and Judge of the Universe—takes one to know one, I guess).

I don't know, man, I don't know: I just don't relate to any of this stuff at all, on either side.

I don't know what any of this stuff is—it takes too much imagination!

People say the schism that opened up in the Orthodox world with the Moscow Patriarchate's excommunication of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople in 2018 may end up as chasmic as the one where Patriarchs of Rome and Constantinople excommunicated each other in 1054, giving us the now almost uncrossable—some say totally uncrossable—abyss between the world of Roman Catholicism and that of Eastern Orthodoxy.

Of course, the idea of Russia as the “Third Rome” (Rome and Constantinople being the first two) has long tantalized its apocalyptic dreamers, an idea perhaps most memorably crystallized in the almost euphorically vatic, heavily Tsar-backslapping non-poetry of the holy elder Philotheus in 1511:

It is through the supreme, all-powerful and all-supporting right hand of God that emperors reign . . . and It has raised thee, most Serene and Supreme Sovereign and Grand Prince, Orthodox Christian Tsar and Lord of all, who art the holder of the dominions of the holy thrones of God, of the sacred, universal and apostolic Churches of the most holy Mother of God . . . instead of Rome and Constantinople. . . . Now there shines through the universe, like the sun in heaven, the Third Rome, of thy sovereign Empire and of the holy synodal apostolic Church, which is in the Orthodox Christian Faith. . . . Observe and see to it, most pious Tsar, that all the Christian empires unite with thine own. For two Romes have fallen, but the third stands, and a fourth there will not be; for thy Christian Tsardom will not pass to any other, according to the mighty word of God.

Not too hard to see that Putin and Kirill are trying to pick up the pieces of this vision, make it fly once again—and maybe they're right.

Or maybe they're wrong, but what they represent is still way better than the rapacious, nihilistic, hedonistic, technocratic, hypnotic, psychotic, vandalizing, demoralizing, corporatizing, virtualizing, atomizing, universalizing, asphyxiating, emasculating, hypersexualizing, Earth-destroying, life-desolating, child-mutilating, depleted uranium-firing, atomic bomb-dropping, war-profiteering, history-erasing, gain-of-function biolab-creating, Mammon and Moloch-worshiping US-led “rules based international order” doing everything possible to run Russia and every other “based” country into the ground.

Or maybe their megalomania will destroy the world.

I don't know, man: So is Moscow becoming the New Rome once again?

Or is Constantinople still the New Rome, and Moscow should acquiesce?

Or is Rome still the old Rome, say my Catholic friends, and so we don't need a new one?

My question is: Do we have to answer Yes to any of those questions?

Because they seem like three sides of the same damn coin, the one Yeshua said to render unto Caesar—three different ways to keep the dream of Christian empire alive, when really it should have died a long time ago, and perhaps never been born in the first place.

It was an interesting experiment, though, or at least an unavoidable one, perhaps worth giving a shot: Theodosius, realizing a vision that began with Constantine, to locate the unity of an imagined community—his empire—in a unity of thoughts in the head, of held opinions:

It is our desire that all the various nations which are subject to our clemency and moderation, should continue to profess that religion which was delivered to the Romans by the divine Apostle Peter, as it has been preserved by faithful tradition...Let us believe in the one deity of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, in equal majesty and in a holy Trinity. We order the followers of this law to embrace the name of Catholic Christians; but as for the others, since, in our judgement they are foolish madmen, we decree that they shall be branded with the ignominious name of heretics, and shall not presume to give to their conventicles the name of churches. They will suffer in the first place the chastisement of the divine condemnation and in the second the punishment of our authority which in accordance with the will of Heaven we shall decide to inflict. (Edict of Thessalonica, 380)

The kingdom of Caesar and the kingdom of God as one and the same kingdom; divine condemnation for dissenters from the Nicene Creed, and imperial punishment, too—banishment to the outer darkness of barbarian lands, and then possibly hell, if it came to that—that's where this was headed in the glory days of Byzantium, and it was a coherent worldview.

Too coherent—totalitarian, basically: That's what my man the Orthodox poet-philosopher, Philip Sherrard, says in his Christianity: Lineaments of a Sacred Tradition:

As the Christian society is founded upon and held together by subscription to the tenets of the Christian faith, the maintenance of this faith in an increasingly inflexible and, one might say, in an increasingly simplified or literal form, becomes an overriding preoccupation, and any expression of the Truth which appears to deviate from this form is regarded as a threat to the stability and security of the universal order which the Church is required to implement. This is why the development of an attitude of idolatry towards dogmatic and ethical formulations, and the idea of the Church as above all a social institution go hand in hand...It was the Church's function, it came to be thought, to mold the secular world in accordance with the principles of right order as embodied in the Christian faith; and this was to be achieved by a more or less totalitarian ecclesiastical state.

Likewise, my man the French anarchist theologian-sociologist, Jacques Ellul, says:

Religion will ensure the unity of the empire, for the God who is One will work on its behalf. But differences in interpretation now become inadmissible. If the religion of the God who is One has this vocation, it has to be united. Heresy is no longer an affair of narrow-minded theologians or hair-splitters. It concerns existence itself, the possibility of the existence of unity, the unity of the empire.

The symphony of Christianity and empire turned heresy into a potentially omnipresent existential threat. Disturbance in the world of thoughts meant disturbance in the world of trees, stones, birds, flowers, and precious human beings; if there were earthquakes, fires, famines, plagues, or the onrush of barbarian hordes, it was God's punishment for unorthodox belief; people had to police their own thoughts and the thoughts of others, lest their world fall to pieces all around them:

I desire to ask one favor of you all, [said Saint John Chrysostom, in his first homily of “On the Statues”] in return for this my address, and speaking with you; which is, that you will correct on my behalf the blasphemers of this city. And should you hear any one in the public thoroughfare, or in the midst of the forum, blaspheming God; go up to him and rebuke him; and should it be necessary to inflict blows, spare not to do so. Smite him on the face; strike his mouth; sanctify your hand with the blow.

If you liked my sermon today, do me a favor, would you—go punch a blasphemer in the mouth; go punch all the blasphemers in the mouth, you'll make your fist holy by doing so.

Which makes perfect sense, and was even maybe a compassionate thing to say, in Chrysostom's now almost vanished, totalizing Byzantine world, I'm not judging him: His sermon series, “On the Statues,” came after a major crisis in his city of Antioch, the anti-tax riots of 387, when hooligans went around toppling and defacing statues of Emperor Theodosius and the imperial family.

Chrysostom was trying to get everybody to be cool, so Theodosius, representing “the will of Heaven” wouldn't come and raze Antioch to the ground, a real concern: Abuse of the emperor's images was an abuse of the emperor himself; it was a kind of blasphemy (blaptaein – injure + pheme – reputation, an injury of an honored person's reputation)—against both the emperor, and now also the God whom Theodosius represented as his image on Earth: "If it be necessary to punish those who blaspheme an earthly king [by defacing his statues],” Chrysostom says, “much more so those who insult God.”

The “punishment” he means has a double sense: On the one hand, just as Emperor Theodosius would have been justified in razing Antioch, to defend his “honor” against the rioters who toppled his statues to the ground, so God, also, would be justified if he chose to destroy the city by earthquake, plague, drought, wildfire, or barbarian invasion, to defend his “honor” against heretics and unbelievers who “insult” him by virtue of their heresy and unbelief.

On the other hand, just as punishment of the few (the rioters) might stave off the emperor's wrath against the many, leaving the city once more in peace, so also if the Christians of the city went around chastising blasphemers—including punching them in the mouth, if it came to that—that might be enough to earn a reprieve from any possible divine annihilation, also.

“Let the Jews and Greeks [=pagans] learn,” Chrysostom says, “that the Christians are the saviors of the city; that they are its guardians, its patrons, and its teachers.” And then he imagines how peaceful everything would become again if those Christian saviors and guardians of the city established a more or less totalitarian atmosphere in the public square in which non-Christians and heretics were constantly afraid of orthodox Christians eavesdropping on them:

They must fear the servants of God too; that if at any time they are inclined to utter such a thing, they may look round every way at each other, and tremble even at their own shadows, anxious lest perchance a Christian, having heard what they said, should spring upon them and sharply chastise them....The blasphemer is an ass; unable to bear the burden of his anger, he has fallen. Come forward and raise him up, both by words and by deeds; and both by meekness and by vehemence; let the medicine be various.

And if John's parishioners can take it upon themselves to administer these various medicines, both gentle and violent, “for the safety of our neighbors,” then brotherly harmony shall dwell in the city again, and all shall be well, he says, thus ending the sermon.

If such an atmosphere of compassionate metaphysical gangsterism seems alien to what Yeshua was doing in the world of first century Roman-occupied Palestine, it was perfectly at home in Chrysostom's fourth century world of Christianized Roman power—and also still very much at home in the twenty-first century, post-Byzantine world of Orthodox nationalism.

When, on January 5, 2019, Patriarch Bartholomew, possibly “a modern apostle of peace and love,” signed his tomos granting the Orthodox Church of Ukraine self-rule, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine was born.

Or, since Bartholomew is actually a “wolf” among the sheep of the Church, who has “surpassed all the heretics” combined, causing “many bleeding wounds on the holy body of Orthodoxy,” no, it wasn't—it was just the fabrication of an “illegal parasynagogue,” nothing more.

Either way, nothing changed about the human bodies or trees or stones in the territory on Earth where the OCU was imagined to exist (or not), except in the way the humans conceptualized other humans: Now that the OCU was the “real” Orthodox Church in Ukraine, those belonging to the apparently more historically rooted and canonical UOC were “occupiers” and pro-Russian “invaders,” who ought to be forcibly evicted from their temples and even tear-gassed and otherwise violently oppressed in all the usual human, all-too-human ways, in the name of “cleansing” true Ukrainian Orthodoxy from the “illusion” of apostasizing Russkiy Mir ideology.

All this makes at least a kind of twilight sense in both Ukraine and Russia, on both sides, where the feeling of existential threat is real, and the desire for a Byzantium-like, totalitarian unity at all scales, and across all dimensions, from the political and economic order all the way down to everyone's innermost thoughts, is an understandably human, albeit still tragic one, probably full of avoidable illusions.

But even in the relatively safe, but still histrionic and pathologically online world of apocalyptic tribalism inhabited by OrthoBros [1,2,3,4], Orthodoxy as an “overriding preoccupation” with correct belief; Orthodoxy as an obsession with drawing visionary lines in the sands of metaphysical thought; Orthodoxy as an “attitude of idolatry towards dogmatic and ethical formulations,” expressed in “increasingly inflexible” and “increasingly simplified or literal form” as the illusory boundaries between a fictional “Us” and a hallucinatory “Them”—even here the totalitarian mood, the omnipresent existential anxiety, of Byzantium lives on, as if by a kind of kaleidoscopic inertia.

And I just want to walk away from that, if I was ever there in the first place.

III. RETURN TO THE WILDERNESS

Byzantium's complete indifference to the world is astounding. The drama of Orthodoxy: we did not have a Renaissance, sinful but liberating from the sacred. So we live in nonexistent worlds: in Byzantium, in Rus, wherever, but not in our own time.

– Father Alexander Schmemann, Journals

Well, what if we did live in our own time—radically so?

If Orthodoxy coevolved with, and, to some extent, for an empire that's now long gone, what might it become if we truly and completely and utterly let that empire go?

Orthodoxy didn't have a Renaissance, as Father Schmemann says above, it's true: But it seems like it's having a Rewilding now, and maybe that's even better.

Let me share a few of the things I'm seeing on that front, a bit scattered, that give me hope for the future:

1.

Father Andrew Phillips' vision of a People's Orthodoxy, a “Real Orthodoxy beyond the Romes,” which he also calls “Carpathian Orthodoxy,” after the wilderness of mountains “on the Western edge of the Orthodox world,” in between empires, but not controlled by them. He envisions this Orthodox localism of the wild spaces as a “way between and beyond the imperialisms of Constantinople and Moscow,” and says it began

with St John the Baptist in the Palestinian desert, it blossomed in the deserts of Egypt and Palestine in the 3rd, 4th and 5th centuries, was taken to both Constantinople and then northwards to the Balkans and then to the forests of Russia and Siberia, but also to Gaul and then to the wild coasts of Ireland and the Hebrides in the 6th and 7th centuries, from where it was taken to both England and Iceland. It is also this spirit of Orthodoxy that was once so alive in the Russian emigration, though now all but dead in the dead hands of the State mentality and the property-thirsty princes of this world. Carpathian Orthodoxy is simply Christianity in life, the uncompromised Christian way of life, Orthodox spirituality. Carpathian Orthodoxy is not Constantinopolitan or Muscovite, not Imperial, but ours, the people’s, that of families, guided by spiritual fathers, by our monasteries and hermits.

2.

Augustine Martin's identification of a Great Shift now happening in post-2020 Orthodoxy, after far and away the vast majority of our hierarchs, at least in America, probably elsewhere, revealed the Byzantine paradigm as, alas, very alive and well: Bishops, archbishops, metropolitans, patriarchs as first of all civil servants, whose first loyalty is to the State: They are there to enforce the civil order, not crash into it with the transcendent, beautifully subversive higher order of the kingdom of God.

When, during 2020, the hierarchs enforced the civil authorities' lockdowns, putting an end to the celebration of the Divine Liturgy, a collective illusion for a lot of people was abruptly dispelled, resulting in widespread feelings of anguish and betrayal: Orthodoxy was apparently just “religion” to the hierarchs; it was something to keep the peace, maintain the social fabric of the State, maybe throw in a little ethnic nostalgia, for old times' sake—something that can wait until the real crisis has passed, not worth dying for.

Philip Sherrard—again, one of the great Orthodox thinkers of our age—goes so far as to say (and I've shared quite a few crazy things he's said in my essays so far, but this is definitely the craziest by far):

Not only must the Church renounce every idea of itself forming, or of itself being party to the formation of, a universal Christian state...It must also renounce the idea that it should constitute a state within a state. It must renounce, that is to say, the idea that Christianity subscribes to the exercise of coercive authoritarianism, whatever form this may take...Where the Church in the Christian East is concerned, this overcoming of its imperio-ecclesiastic inheritance demands that the Church reform the pattern of the episcopal hierarchy in so far as this was established to conform to the requirements of imperial administration and jurisdiction. Such a pattern constitutes a total anachronism...At the same time the panoply of grandeur and sovereignty with which the bishops were invested in imperial times and still assume is quite out of accord with the understanding that each Christian is equally a representative of the royal priesthood as every other Christian, clerical or non-clerical.

Sherrard said it, not me!

What I say—as just some dude imagining possible bridges from here to Sherrard's future—is: Without being obnoxious or overly rebellious about it, and especially without justifying ourselves with true Orthodoxy is this, true Orthodoxy is that, we can try to live such a coherent life together—physically together, not online—at the scale of the parish (possibly the only scale at which Orthodoxy really exists, rather than being collectively imagined)—it makes things like bishops and metropolitans, patriarchs and archdioceses and jurisdictions, not very real—at least not as real as our actual, face-to-face Eucharistic life together.

3.

I heard a story a few years ago of a bunch dirty, dreadlocked hippies at the Burning Man festival, of all places, spontaneously praying the Jesus Prayer, without ever having been Orthodox, or even Christian, and when I heard that story, something in the cave of my heart twanged like some bonkers rainforest harp, and I furiously and effortlessly wrote a poem, which goes like this:

BURNING MAN

christianity hangs dead for me

until i remember

the children of the burning heart

out in the irradiant sands

of the American southwest crying out

lord jesus christ, son of god, son of god

.dreadlocks billowing in elemental winds

like the wild manes of boxcar children

strung out on El Shaddai,

most high,

the beautiful barefoot mamas

like eve coming naked

from the lungs of adam asleep

in divine ecstasy

or the mother of cain on hands & knees

sniffing like a lioness

after the wild roots of EdenI love that stuff, man, I love it—I recognize such kindred spirits in these people, a kind of collective dirtbag Prometheus stealing the holy fire of Byzantium and running into the desert with it—Franny and Zoe stuff, Way of the Pilgrim meets Dharma Bums-backpackers in the ruins of someone else's empire, the beautiful edges and in-between, which, for Wild Orthodoxy, are exactly at the center.

4.

And perhaps most of all a paragraph (from Brendan Legane) the forest-loving, myth-singing, recent Orthodox convert

quoted in his recent beautiful, important, and profound Wild Christ Not Feral Christ:Into an atmosphere of fear and deception walked bands of Irish with a clear and unequivocal sense of purpose. That purpose had nothing whatsoever to do with vendettas or luxury of making money or winning territory; little with emaciating themselves into scrawny and impotent worshippers of a far-removed god. Worship came first, but good worship presupposed good health. They revived long-term farming methods on the land they took over. With the product they fed themselves, gave free provisions to the needy, and sold the rest to expand their activities…they showed how to order things for the best in circumstances that were far from good. And in their dealings with people showed little fear or favour to rich or poor…

“I love it,” Martin said. “That's It. At least for me.”

That's it for me, too, brother—for a lot of us: That's the way of the future.

love,

graham

This is great, Graham. I'm with you.

One thing occurs to me as I read: in early Ireland, the faith was monk centred. Abbotts rather than Bishops took the lead. That seems right. I think we still need the hierarchies: who else will guard the tradition? We are not protestants, after all. There has to be a centre. But the job of the centre is to hold the truth so that the margins can pursue it truly. Which is up to us.

I love this and I love you, my friend. I wasn't sure what I wanted to be when I grew up before reading this, but an illegal parasynagogue might be in the running now. I am taken with the image of the mother of cain animal-ing out after the roots of Eden. I think the almost Hobbesian fear of this sort of casting-off from hierachy island going too far would be more charming if there was even a faint possibility that the Church often stumbling into such open-hearted chaos was at the root of the centuries of stupidity and murder.

A living way that trues the space between it and others with love and beauty is the only guard for one's particulars. I suspect the anther and pistil of the word of G-d is heavily clustered in the human imagination. As such it seems more likely to flourish in wind and the symbiotic mix of life around it than under the glass at some self-identified center. I have often wondered if the burying of the talents in the Yeshua's parable refers to this guarding of truth. What you bind on earth is bound in heaven and what you loose on earth is loosed in heaven. Just an outsider here, but I think lads (and it has been mostly a phallic project) who cannot bear the thought of a trueing that is more mutable than fixed and more multivocal than monologued have won the day for centuries and the world around them has grown grey with their breath. Why not give standing on the other foot a whirl for a bit of a minute. You can always go back to punching heretics and Jews in Chrysostomesque granduer if cats of your dogmas start sleeping with the dogs of some slinky catechism. G-d is the type of memory for which repetiton without innovation is the gateway to dementia. In the end, I am looking in from outside. Not an intact tablet guy. Not even a broken tablet safe in the box guy. More of a dust of the tablets on the tail fur of a hare tangled in the robes of Klee's Angel as it all blows out from Eden kinda guy.