“This is the way we dream of Eden. We cannot help feeling that it still exists, but just beyond our reach—beyond the wall of dark fire kept roaring by the cherubim of the brain.”

— Evan Eisenberg, The Ecology of Eden

I. BACK TO THE LAND

If you know my writing a little bit, you know I have an attraction to Hebraic thought. This goes beyond calling Yeshua by the name his mother gave him or referring to him as the “Messiah” rather than “Christ”—though I think these two word choices in themselves will have their cosmic ramifications. And it goes beyond working on versions of the psalms from the Hebrew, too, ignoring the Septuagint and its abstract, avoidably vacuous liturgical derivatives in English, though the discovery of a vivid, alive, earthy, embodied vocabulary through which to re-articulate ancient truths has been exciting, and also very helpful, to me and I suspect others—I hope so, anyway.

It goes beyond these things, but I don't know how far beyond—pretty far, I think. The terrorist massacres of the deathcult Hamas on October 7 reawakened for me a love for Israel—as an idea, a story, a dream, a people, a specific place on Earth, with each dimension rooted in the others. It's been strange and somewhat alienating to observe how the set of feelings evoked within myself has been more or less the exact opposite of the tens or hundreds of thousands of worldwide masses in the streets yelling Hamas slogans through their megaphones about an ethnic cleansing of Jews “from the river to the sea”—I don't relate to that at all. And I find it bewildering that so many people do.

And I also don't relate to the “We're beyond all this, the real Israel has nothing to do with an actual place on Earth” attitude so prevalent among my fellow Eastern Orthodox, either. As just one example, here's a typical ROCOR priest a few years ago:

I must tell you what the Orthodox Christian understanding of the Promises is: it’s not about earthly lands, favored nations with special land rights, earthly kingdoms, and earthly Jerusalems; it’s about Christ, His Church and a heavenly Jerusalem.

I understand what this priest is saying, and it's of course exactly what he's supposed to say, but it doesn't resonate in me at all. And I don't think it resonates with what's happening now in this historical moment, except in an inside-out way, as an illustration of the kind of slim-bodied ascetical nihilism which helped generate the very problems it proposes an escape from.

In the predawn pain and confusion of the old order passing away before anyone can really see what the next order will look like, many of us orphans of the death of Christianity are looking for a way to recover a sense of place, a sense roots in the Earth, a sense of renewed fellowship and indigeneity in the post-apocalyptic wasteland of the Machine. So for us, if we have any feelings left for the biblical story at all, the last thing we need to deny is that the Promised Land has anything to do with the actual land that was promised. And perhaps the first thing we need to affirm is that the biblical vision is about the realization of a particular way of life on Earth, not somewhere else.

In this essay, and perhaps the next three or four, I want to explore what Israel could mean within the field of meaning that's been opening up on my sojourn through this wilderness of writing. That's as much as I can do, really; I hope you'll find the effort useful for you as you walk your own path.

(Note: I call the city here “Yerushalayim” not “Jerusalem,” for same reason I call the Messiah “Yeshua,” and not “Jesus.” It's nothing against our Anglo hard J; when I go jogging, I'm glad that the word in English is as onomatopoeic as it is for what my flat feet are actually doing to the sidewalk. Rather, it's that “Yerushalayim”—which, according to one etymology, means “Rain of Peace”—sounds beautiful, and is beautiful. Also, calling the city by the name used by the Hebrew speakers who lived there long ago, and live there now, is itself a way of being open to what they have to say about it).

II. THE LOCATION OF THE COSMIC LITURGY

This morning I went out barefoot in the grass: peach sunrise, periwinkle sky.

The dawn breeze gusted through the alder trees and oaks and willows, and chickadees were singing and scratching in the leaves. I was so happy!

And then I noticed the crescent moon floating above the apple tree, looking as spherical as it ever has to me—like a huge, bright-edged water droplet of silver you could just drink through a straw—and the morning star, Venus, was only a fingertip away!

How lovely, how vast all this is!

Across the brown reeds of the marsh, a lonely dog was barking, his voice reverberating across the huge amount of new space that seemed to stretch from inside my cavernous skull of calcium, all the way up to Venus and the moon—I don't know, man, what can I say about all this? (probably nothing); it was totally rockin'.

The beloved third century heretic, Origen, responding to a pagan critic who in the second century mocked the followers of Yeshua for not having temples, altars, or holy icons, said: “The whole universe is God's temple.” (Against Celsus, VII)

And I love that, man, and I feel that. And I feel that more and more.

I find myself more and more, when I'm standing in church for the Divine Liturgy, looking out the window, thinking about what's beyond the window, somewhere: Green grass, yellow sun. Broken stones, wild oats, morning glories, sage. Thistle flowers, clover. Cypress trees, sepia mountains, redwood forests.

A couple of Sundays ago, out of the corner of my eye through the window, I kept thinking it was snowing, but it was the tangerine-yellow leaves of a ginkgo tree, backlit by the sun and falling in bright, summerlike flakes across the blue air.

I often daydream, imagining how happier I might have been singing liturgies in the Hebrew Temple, most of which was totally open to the breeze and sunlight. The Temple in Yerushalayim, unlike the later Hagia Sophia or its derivatives, wasn't its own self-enclosed reality, with a dome symbolizing, but also visually obstructing, the sky. It wasn't just the roofed structure at its focal point (the Holy Place enclosing the Holy of Holies) but also the whole holy complex itself—almost a small city, including the vast, white-stoned plazas surrounding the structure of the Holy Place.

And it was in these plazas, or courtyards, under sun and clouds, that people would gather for song and prayer—and the birds, also:

How lovely are your dwelling-paces,

O Yah of the Myriads!

My breath yearns, even faints, for the courts of Yah!

My heart and my flesh sing for joy to the Living One!

Even the sparrow has found a house,

And the swallow a nest for herself, where she may lay her young

Near your altars, O Yah of the Myriad Living Things...

(Ps. 84:2-4)

And it was from these white stones in the open air—with a physical line of sight to the forms of nature they were singing about (sapphire sky, cedar forests, silver moon)—that the Hebrews would invite the rest of Earth into the liturgy of this Temple of theirs that now included the whole universe:

Hallelu Yah!

Praise Yah from the skies!

Praise him in the heights!

Praise him, sun and moon!

Praise him, all you stars of light!

Mountains and all hills,

Fruitful trees and all cedars,

Living things and all beasts...

(Ps. 148:1-3, 9-10)

The mountains and hills, especially so—for the Hebrews, they are the fountainhead of life on Earth, and the place where all life is called to return.

III. FROM THEM GREAT RIVERS FLOW

In his majestic Ecology of Eden, Evan Eisenberg distinguishes two fundamental mythic orientations in the ancient Near East: “For one, the heart of the world is wilderness,” he says, “For the other, the world revolves around a city, the work of human hands.”

The Canaanites were of the first school, brought to perfection in the Hebrew scriptures: The center of the world is Eden, the “towering cedars in the garden of God” (Ez. 31:8), a forested mountain down from which the rivers of life flow in all directions (cf. Gen. 2:10-14).

The Mesopotamians were of the second school, of which the Babylonians Enuma Elish is the highest expression: The center is a ziggurat, a pixelated mountain, surrounded by a circuit board of hand-dug canals, which arose from the shimmering sun-mirages of the plains through godlike human feats of technological mastery.

Each fundamental orientation is of course rooted in the fundamental experience of each people in its own land. The Babylonian conquest of nature gave, in its own day, the impression of being total, and because of this, life outside the city had become totally unimaginable. As Eisenberg says:

Instead of recipients, they came to think of themselves as the source of life and plenty. They controlled the waters, tapped the great rivers like kegs of beer. It was easy to forget that the water came from somewhere. They had agriculture down to a science. It was easy to forget that it had arisen among the savages of the hills. The storehouses spat out grain; the markets were littered with dates and slippery with oil. Surely the city was the source of all life.

And today Mesopotamia (Iraq) is a manmade desert, its ancient ziggurats and canals long since vanished into to sand. The myth of the Babylonians was the wrong story, a failed map; it led them astray, destroyed their world, ripped away their roots, scattered them in the winds of time.

The Canaanite orientation away from the city, and towards the forested mountains, as the center of life, was more realistic, more deeply rooted in Creation:

The World Mountain is mythic shorthand for an ecological fact. There are certain places on Earth that play a central role in the flow of energy and the cycling of water and nutrients...They provide fresh infusions of pollinating birds and insects, which grant continuing life to many of the plants (both wild and cultivated) we take for granted...They are spigots for the circulation of wildness through places made hard and almost impermeable by long human use...

“All such places,” Eisenberg says, “are more or less wild; many are forested; many are mountainous, and from them great rivers flow.” Eden is the mythically vibrant, crystallized Hebraic image of such places as a unified phenomenon, but it's not thereby located in some Platonic wonderland beyond the stars: Two of the four watercourses listed in Genesis as flowing in the four directions from Eden are the Tigris and the Euphrates, not mythical rivers; Genesis wants us to know that Eden is rooted in the transcendent High One, and exists here on Earth, not elsewhere, as is always the case with the Hebrews: “The Earth is full of your lovingkindness, Adonai—teach me your decrees” (Ps. 119: 64)

Eisenberg continues:

The mountains of Lebanon, Syria, and Armenia are the source of water for much of the Near East. From their slopes flow the headwaters of the Jordan, the Orontes, the Tigris, and the Euphrates. The pattern is copied on smaller scales as well, in the brooks, wadis, and underground aquifers that slide from the Judean hills to the coast.

Forested mountains as an everflowing source of life from God was something the Canaanite farmers could experience at the scale of their own terraced gardens in the Judean hills. It wasn't just the mountains' life-giving redirection of rainwater, and their relative inaccessibility to human destruction (unlike the Mesopotamian plains), but also the interaction of their geometries with the rhythms of the sun: “On hillsides,” Eisenberg relays, “a wide range of climates can be collapsed accordionlike within the space of a few acres,” offering a cornucopia of wild plants for farmers to choose for resilient cultivation. Also, the first domesticated animals in Canaan weren't fed grain (the humans themselves needed all they could grow), but like their wild ancestors “followed the grass, the brush, and the seasons” and what enabled farmers to keep such animals was that they “lived in the hills, where the seasons crept up and down the slopes instead of (or as well as) gliding hundreds of miles north and south.”

All this is true of the ancient Canaanites in general, not just the Israelites of Canaan in particular. The Hebrew bible gives clues about who the Israelites really were, in their own self-understanding, which made them distinct from other Canaanites, though they lived in the same place and in much the same way.

The story of their Hebrew ancestor, Abraham, being called by God out of the gleaming metropolis of Ur to migrate “to the land I will show you,” hints of a people who had once been of the urbanized Mesopotamian ilk, but had a heard a voice calling them to return to the gardenable wilderness. The memory of an exodus from the Egyptian empire hints at much the same thing. Eisenberg's favorite theory—mine also, because it rings the same anarchist bell that

rings in his lovely essay, The Jellyfish Tribe—is that “The Israelites were land-starved or tax-gouged peasants who threw off the rule of the lowland warlords and staked out their own territory in the hills, acting out the passion for justice and equality that would later find its voice in scripture.”However this came to be, the mountains of Canaan were life to the Israelites; they were the axis of the world, they were the garden of God. Thus, after the destruction of Yerushalayim by the Babylonians, when God wants to comfort the exiles, he speaks of their future life together, God and man, back home in those mountains:

I will shepherd them upon the mountains of Israel, by the streams...their grazing place will be on the high mountains of Israel...I will tend My flock and make them lie down. I will seek the lost, bring back the stray, bind up the broken and strengthen the sick...I will make a covenant of shalom with them. I will remove the evil beasts from the land, so they may dwell safely in the wilderness and sleep in the forest...I will cause the rain to come down in its seasons. There will be showers of blessing. The tree of the field will yield its fruit. The ground will yield its produce. They will be secure in their land...

(Ez. 34:11-27)

So great is the High One's love, not just for the people of Israel but also for the mountains they belong to, that he speaks to the mountains themselves, as if to living persons:

You, mountains Israel, you will shoot forth your branches and yield your fruit for My people Israel, for their return is near. For behold, I am for you. I will turn to you. You will be tilled and sown. I will settle a large population upon you—the whole house of Israel, all of it. The cities will be inhabited. The desolate places will be built up...They will say, 'This land that was a wasteland has become like the garden of Eden.'

(Ez. 36:8-10, 35)

And if the elevation of the city of Yerushalayim itself, as the heart of this mountainous terrain, is often amplified in the scriptures to something more like the stratospheric heights of the mountains of Syria or Lebanon—

Great is Adonai, and greatly to be praised

in the city of our God—His holy mountain.

A beautiful height—the joy of the whole Earth—

is Mount Zion, on the northern side of the city

(Ps. 48:2-3)

—this is only a way of expressing their vision of Yerushalayim as a city whose origin, inner meaning, and destiny is the mountain of God itself—the garden of Eden.

IV. THE RIVER OF LIFE

The image of Yerushalayim as a city coming from, and becoming again, Eden, is painted in many places in scripture, perhaps none more beautifully than in Ezekiel (Yechezqe'l, meaning “Yah is strength”).

During the long years of his exile in Babylon, Yechezqe'l stood on the banks of the river and murmured to the Holy One in his heart. And several times he was snatched away into the iridescence of prophetic ecstasy, and saw things, touched things, heard things, tasted things way beyond the power of human language to describe.

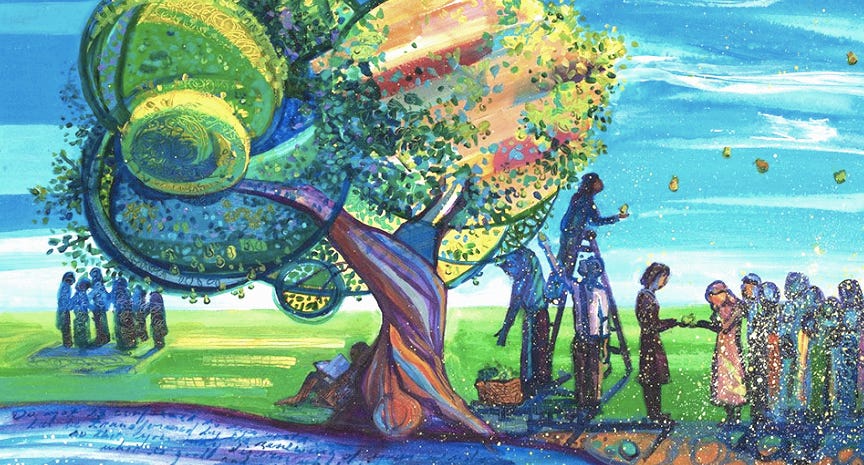

And so when he did describe them in human language—beautifully so—they came out as the wild primary colors of a young child's earnest, but crappy, crayon drawings of Earth as the Burning Bush—the whole Earth, as it were, floating in the oceanic rainbow-fire of the love of God.

“In visions God brought me to the land of Israel,” Yechezqe'l says, “and set me down upon a very high mountain. On it, toward the south, was something like the construction of a city” (Ez. 40:2). A kind of angelic android—a man “whose appearance was like bronze,” perhaps a walking memory of the Bronze Age collapse—leads him around the dreamlike mountain-city, using a plucked reed to measure the many perfections of its geometry.

It turns out the city is Yerushalayim herself, as seen within the iridescent clarity of prophetic vision. And the whole city is a Temple now, its limewashed walls and cedar gates covered with carved images of cherubim and palm trees, recalling Eden, and none will live in her now but priests (a priest being one who offers all Creation to God, and God to all Creation).

Everything is radiant with the sunlike presence of God in Yerushalayim, now dawning in the gateway of the East (43:2). The voice of this new Sun is “like the sound of many waters” and Yechezqe'l also sees cool water flowing from near the altar, through the threshold of eastern gateway, streaming away to the east. With the man of bronze, he follows it, and measures its depth as he goes—only as high as his ankles at first, then up to his knees after a thousand cubits. After another thousand, it was up to his waist. Another thousand, and it's too deep to walk in; it's only for swimming now.

“These waters go out toward the eastern region,” the Bronze Man says to Yechezqe'l. “They go down to the Arabah and enter the sea”—the turquoise-colored Dead Sea, of course, rimmed by crystalline beaches of white salt, inhabited only by the hardscrabble likes of cyanobacteria and algal blooms. And then the river of life flowing from the Temple arrives:

The waters of the sea will flow and become fresh [lit. 'healed.'] It will be that every living creature that swarms will live wherever the rivers go. There will be a very great multitude of fish, because this water goes there and makes the salt water fresh. So everything will be healed and live wherever the river goes

—a new Creation—“Birds in the air, and fish in the ocean / All swimming through the paths of the seas...” (Ps. 8:8)—very much singing the same song as the prophet Isaiah (Yeshayahu, “Yah is salvation”):

The wilderness and dry land will be glad!

The desert will rejoice and blossom like a lily!

It will blossom profusely,

will rejoice with joy and singing...

For water will burst forth in the desert

and streams in the wilderness.

The parched land will become a pool,

the thirsty ground springs of water.

In the haunt of jackals, where they rest,

grass will become reeds and rushes...

The ransomed of Adonai will return

and come to Zion with singing...

(Is. 35:1-2, 6-8)

And also:

The poor and needy ask for water,

but there is none,

Their tongues are parched with thirst.

I, Adonai, will answer them,

I, the God of Israel, will not forsake them.

I will open rivers on the bare hills

and springs in the midst of the valleys.

I will make the wilderness a pool of water

and the dry land into fountains of water.

I will plant in the wilderness

the cedar and the acacia tree, the myrtle and the olive tree.

I will set in the desert the cypress tree

and the pine together with the box tree—

so they may see and know,

consider and understand together,

that the hand of Adonai has done this,

the Holy One of Israel has created it...

(Is. 41:17-21)

The life of the Holy One will flow as a river from Yerushalayim, transforming the Judean desert into a blossoming garden again, so that the hungry and thirsty of the world will know that it was Yah himself, the Creator, who walked in Eden “in the cool of the day,” who made it happen—so they can embrace him as the Father of All, with new hearts like the hearts of children, rejoicing with the children of Israel and the rest of Creation, also, sitting down peacefully, each within the flickering green shadows of his or her own fractal recap of the garden Eden, greeting the sunrise of the Messianic age:

But at the end of days

the mountain of Adonai’s House will be established as chief of the mountains,

and will be raised above the hills.

Peoples will flow up to it.

Then many nations will go and say:

“Come, let us go up to the mountain of Adonai,

to the House of the God of Jacob!

Then He will direct us in His ways,

and we will walk in His paths.”

For Torah will go forth from Zion,

and the word of Adonai from Jerusalem...

They will beat their swords into plowshares,

and their spears into pruning shears.

Nation will not lift up sword against nation,

nor will they learn war again.

But each man will sit under his vine

and under his fig tree,

with no one causing terror...

(Mic. 4:1-4)

—a dream which, yes, is as childish as it gets. And only someone with the jumbo-sized crayons of the Hebrew prophets could draw it in all its utterly slapdash utopian hues.

V. THROUGH THE RAIN OF THE HEAVENS WILL SHE DRINK WATER

“Every autumn, over 500 million birds cross Israel's airspace,” this article says. “Israel sits on the junction of three continents,” says an Israeli scientist in the article. “Politically, it's a disaster, but for bird migration, it's heaven”—you can see whole rivers of life flowing through the sky.

“Canaan as a whole,” says Eisenberg, “situated at the junction of three continents, has always been a maelstrom of gene flow. Even today its genetic diversity is dazzling, with flora and fauna of Europe, Africa, and Asia mingling in sometimes unsettling ways. A few thousand years ago, when the region was less bruised by human use, the mix was more dazzling still.”

And what draws so many plants and animals through the corridor of the Holy Land is what also drew the dazzling swarms of many-colored humans:

One was its site at the middle of the world, the crux of trade routes between Europe, Asia, and Africa; the other was its bristling mountains

—the mountains as a beautiful refuge from chaos, as homes to a thousand microclimates and rain-catchers and channelers of rain, as fountainheads of wilderness transcending man's self-destruction, and circulators of the atmosphere, and of energy and nutrient flows—this is why “for five thousand years Canaan was a prize of contending empires.”

And still is, of course!—death, anguish, clamor in the Holy Land, “nothing new under the sun.”

Which makes it, according to God's savage logic, the perfect place on Earth to reveal—as “a light to the world” —what his way of life is really like—the kingdom of God, as holy, i.e. totally separate and distinct from the life-devouring machine of the kingdoms of men.

And although the phrase “kingdom of God” doesn't appear in the bible until Yeshua appears in the gospels announcing its arrival, the idea of God as Israel's one true King is there from Genesis onward: It's perhaps the fundamental note in the three-note chord plucked again and again on the harp of the Hebrew prophets: No king but God, no God but Yah, no home but the hillsides of Eden.

The many beauties and disasters of the Davidic monarchy aside, the idea of the kingdom of God is not the same as theocracy—the bible says outright that to surrender to any human on his throne is to reject God as one's only king (1 Sam. 8:7). Rather, the kingdom of God is something more along the lines of a mystical anarchy, whose peaceful order appears spontaneous, because it emerges from everyone listening to the voice of God within the depths of his or her own heart:

I will put My Torah within them.

Yes, I will write it on their heart.

I will be their God

and they will be My people.

No longer will each teach his neighbor

or each his brother, saying: ‘Know Adonai,’

for they will all know Me,

from the least of them [the powerless] to the greatest [the most powerful]

(Jer. 31:32-33)

The mountains of the Holy Land were, and still can be, the training grounds for such a transcendent politics. As Rabbi David Seidenberg says, drawing on Seidenberg's Ecology of Eden to interpret Deut. 11:12, “The land where you are crossing over to is a land of mountains and valleys—through the rain of the heavens will she drink water”:

A land that must drink from the heavens...is a land subject to drought. And yet the Torah teaches this is the ideal land...because 'the eyes of YHVH your God are continually upon her.' This mystical-sounding relationship describes a simple ecological reality, imagined from a divine perspective: the lack of human control over irrigation means that God is continually assessing whether the people merit rain....Unlike Egypt [or Babylon, in both of which water is under technological control], the feedback loop in Canaan is short and swift...It is that very fact—that everyone's tenure is tenuous—that makes Canaan/Israel a holy land.

At the same time, as a land bridge between three continents over which empires have been jogging back and forth like the reverse Johnny Appleseeds of apocalyptic destruction for the last five thousand years, if one puts one's trust in the M16, one's hope in the M16 will inevitably be dashed sooner or later by someone else's M16 (and probably sooner rather than later). Conversely, if there ever is true peace in Israel—lasting peace, not yet another Pyrrhic victory making the great wheel of chaos go 'round, only so it comes hurtling back again—everyone will have to acknowledge that peace as something which could only flow from the love of Israel's God himself, not constructed in the usual manner from the carcasses of the slain.

That the land itself is less subject than most to the technological control of nature, but also more subject than most to the control of imperial powers, means that the land itself can cultivate the kind of childlike trust necessary for the realization of God's kingdom on Earth: In a land watered by the heavens, look closely at the lilies of the field, et cetera. And it is this dual aspect of trust, as an embodied, very human energy acting in ecological and political directions alike, is what I understand “rain” and “peace” could mean in Yerushalayim's name, “Rain of Peace.”

VI. BACK TO THE HORIZON

Well, I don't live there. People who do live there are free to naysay anything I've said—I always want to learn.

I offer this only as a way to take seriously this land I don't live in, but whose stories I'm trying to live by—and perhaps also as the beginning of a way to see Israel as a kind of gravitational force for the actual physical landscape I wish to become rooted in, using her stories.

I am naive, but not so naive as to think that just because the modern State of Israel has the word “Israel” in it means it's an organic continuation of the dream of Israel as remembered by the Hebrew bible. Maybe it is; maybe it isn't. People who believe in the dream of Israel can say, especially those who live there. I've said nothing in this essay about states either way—which are collective acts of imagination, and less real than people, trees, and mountains—other than that a lot of them, for thousands of years, have been vying for control of the land of Israel, and still continue to do so.

But I wouldn't say, as a recent Orthodox writer did, in his article “4 Reasons to Support Palestinians, but not Zionists or Hamas” that

The Orthodox Catholic Church is Israel from a Christian Theological perspective. For Christians, the modern State of Israel has no connection to the Kingdom of Israel whatsoever.

There obviously is a connection—the land itself, and the prismatic dreams of the prophets of the land itself blooming again like a thousand Edens.

Secondly, I'll say this boldly, and with a love in my heart that goes beyond the bland song and dance of ecumenical pussyfooting: I believe that Yeshua is the Messiah, and that the kingdom of God has already begun to dawn in him, in an unexpected way—and that non-recognition of this reality will mean wandering from one blind alleyway to another. But I wouldn't etherealize the kingdom of God into have nothing to do with real trees blooming in real deserts in the real Israel on the real Earth that he himself created—I think that's crazy.

And I'm beginning to wonder if the long history of etherealization I find myself rebelling against actually has its roots in the transfer of Christian attention from Yerushalayim—watered from the heavens, beset by empires—to Rome, a city virtually synonymous with the technological control of nature and the glories of imperial conquest.

love,

graham

End note » If this piqued your interest, I strongly encourage you to read Rabbi David Mevorach Seidenberg’s essay, The Third Promise: Can Judaism’s indigenous core help us rise above the damaging politics of our time?

Thanks for this, Graham. It’s complex, provocative and shimmering with an old beauty. I went to the Holy Land once, and standing on the Temple Mount, an indescribable feeling rushed into me, causing me to think something like, “Ohhh, I see, this place actually is holy.” It’s not a metaphor in any way. My short visit there was one experience like that after another, in both directions. Coming down from that very literal hill of sacred experience, a rabbi interrupted our group to talk about bombs while a group of American Christians in pink shirts reading “Powerlifters for Jesus” cheered him on.

But I have to say, in my own prayer journey, even as I return to the Christ path, that place has not been central. After reading your essay, part of me sees this is just because I have never drank in these complicated, holy stories in the ways you and others have. I want to do that now. But there’s this line toward the end of your writing I keep wondering about: “I offer this only as a way to take seriously this land I don’t live in, but whose stories I’m trying to live by...” It strikes me that the tension in my own prayer journey is the opposite of this. I am trying to take seriously this land where I live (I know you are, too), meaning that I wonder about how it is also holy in particular ways – not metaphorical ways. I believe the land longs to be related with in these ways, or God longs to be related with in these ways through the land. And yet I can never live by this land’s stories because I don’t know them. The peoples who know the deep, sacred contours of this North American continent are not my ancestors, and the ancient stories that relay the actual, sacred Presence as it manifests in the land here are told completely outside the Christian or Hebraic cosmology. What to do about that, I don’t know. But your article has provoked a lot of interior wondering about it – and tension – so thank you.

Graham, as usual, thanks for the thoughtful and passionate content.

One concept that's helped me navigate all this stuff personally is that Jesus actually becomes the bridge between the "Jew" (the visceral, the embodied, the concrete, the tangible) and the "Greek" (the ethereal, the philosophical, the abstract, the conceptual): that in following Christ, we can connect Heaven with Earth. He has healed this tension and prepared this reconnection, this rebinding (religion, re-attachment of ligaments) by undergoing the fullest intensity of animosity from both worlds, being suspended between heaven and earth, rejected by his Father and his Bride simultaneously.

I think that, since the enlightenment, the modern western world has lost touch with or failed to fully appreciate the importance of the truth of the Jewish life (the law and the prophets) and instead has a tendency to over-emphasize the Greek truth. I believe that a reintegration of the earthy and carnal principles of Judaism, without discarding the light and vision of the Greek principles, will truly be re-orienting for our culture and society: "I have not come to abolish the Law and the prophets, but to fulfill them".