“I have heard the forest murmur of thee mysteriously, and the winds sing thy praise as they stir the waters. I have heard choirs of stars preach thy glory as they keep their tracks in the depths of infinite space...”

– Orthodox Christian Prayers, ‘Glory to God’ akathist

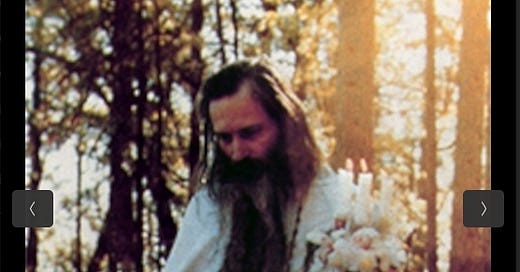

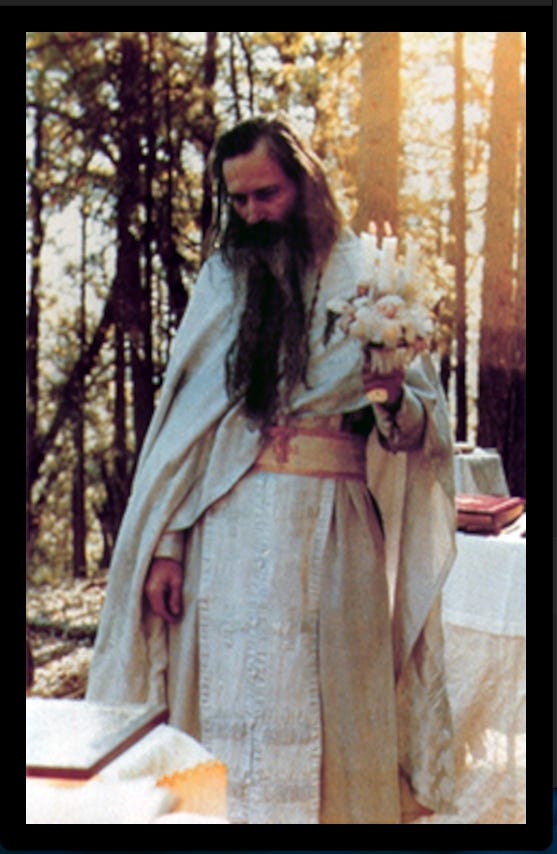

I've been making an Orthodox temple in the forest where I hope one day to live.

It has neither walls nor roof; rather, its walls are blue air and living aspen trees and birch, its roof is just the sun and sky. The whole thing is a grassy slope running upwards towards the East, towards the sunrise.

At the end of the slope is an altar table on top of a sanctuary platform made from logs, boulders, and packed earth covered in moss. There are flat, gray stones for our priest to stand on as he sings in front of the altar, whose four posts are ironwood logs with the bark still on them, sunken in the dirt. Its surface is rough-cut cherry boards full of insect holes and other gaps and imperfections. Outside the earthen platform are icons of Yeshua and his mother mounted on posts of birch.

This is all there is in terms of an iconostasis, and all there needs to be. The icons are partially sheltered, but still the wind and rain and especially the sun touch them, and they become faded. To make up for this, our friend swamps them in bouquets of wildflowers whenever there's a liturgy.

Can you do that? Hold the Divine Liturgy in a temple which has more or less sprouted in some whatever-forest like a patch of wildflowers, rather than designed, financed, and constructed in the usual manner?

There is a story from the Vyatka labor camp—part of the Soviet gulag, in the remote wilderness of the taiga—of the childlike holy elder, Father Pavel Gruzdev, serving a liturgy with other prisoners, though they had no temple, no vestments, no chalice, no bread, no wine—no nothing, except for their own precious human bodies and the impenetrable forest. “As in the first Christian centuries, when worship was often performed in the open air,” the story goes, “Orthodox Christians went out into the forest and began to worship in a forest glade.” For the wine, they made juice from wild blueberries, strawberries, lingonberries, and blackberries. For a censer they had a tin can; the priests' vestments were prisoners' rags; the bishop's throne nothing more than a tree stump: “High pines, grass in the glade, cherubic throne, blue sky, wooden bowl with the juice of forest berries—everyone wept, not from grief, but from the joy of prayer.”

Children don't mind using a tin can for a censer—no need for a cup of gold hanging from golden chains—not so much because they don't see the tin can for the gold cup in their mind's eye; rather, to a young child, all things—whether birds or rocks, whether clouds and flowers, or trash falling out of the industrial world—already have the luminous, exalted quality of the Divine that ornate gold plating must convey to grown-ups only dimly.

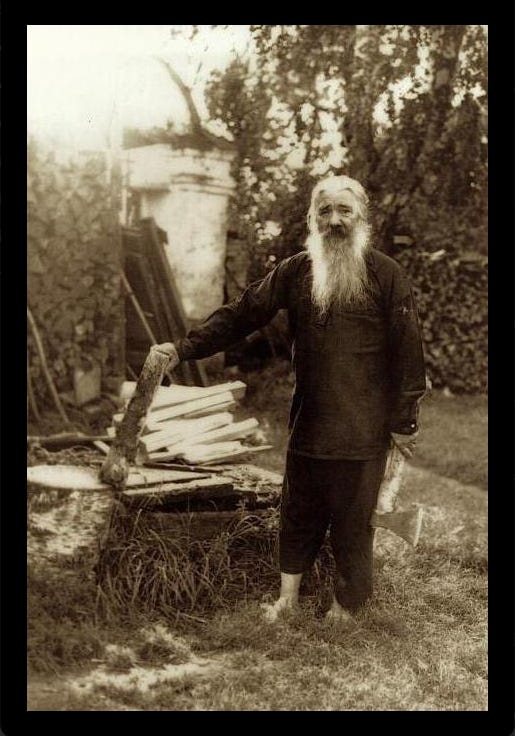

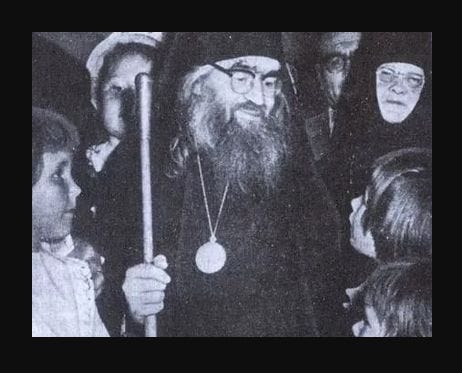

Stories of Orthodox saints who have recovered their original, pristine, fiery, childlike vision of life are endless: Saint John of San Francisco, a bishop who served the Divine Liturgy in his cathedral barefoot, wearing a bishop's miter (ceremonial headdress) made of cardboard, given by his beloved orphans; Saint Paul of Obnora, who in remote Siberia lived in the hollow of a linden tree “glorifying God together with the birds” and “living on grass and roots and enduring all changes in weather”; Elder Isidore of Gethsemane Skete, who when he received bishops as guests, had them sit in his garden upon “couches” made of branches, logs, and old boards, and sent them away with a handful of blackberries he'd been saving, or some other such gift, which for a child would have meant giving away almost the entire world.

The temple I'm building has spent the last four and a half billion years being built by God—that's why it's so beautiful, though I've hardly done a thing: trillium flowers, blue-violet lupine, butterfly milkweed, Indian paintbrush, prairie blazingstar, ox-eyed sunflower, black-eyed Susan, purple aster, goldenrod—imagine you had to assemble these yourself, atom by atom, with an eye to their manifold unfolding relationships with the rest of Creation also: iridescent hummingbirds, quaking aspen with sun-yellow leaves in the fall, black basalt rock spewed from an ancient volcano, white temple-like columns of birches in the distance—and the perfect timing of the snow and rain, the blue expanse of sky, the low clouds floating in it like frozen splashes of cream.

In the story of the garden of Eden, Adam and Eve are co-creators with God, but neither co-powerful nor co-wise: The little path of smooth stepping-stones leading through the grass to the altar—my son made that. But the stones he used, the grass, the dirt, the little boy himself—our heavenly Father made those…

As I work, I try to do things in a slow, quiet, listening way, so that what I do unfolds almost as naturally as a flower. When I made the outline of the solea—the sanctuary platform—out of fallen logs, there was no diagram or blueprint I was trying to replicate, no measurements, no dimensions. Instead, I arranged the logs into a polygon that felt right, and then I kept looking at it from all angles and adjusting the logs a little more here, a little more there, until something “clicked” geometrically and it felt right, and the whole arrangement emanated solidity, goodness, and life.

The result was an irregular hexagon, a beautiful shape I would have been unable to sketch on paper with any exactness. And then after filling the log outline with earth, I found various boulders and heaved them into the corners, and then smaller stones, and then even smaller ones—a smooth gradient of scales lending solidity to the whole; that was my intention, anyway. With the placement of every rock, I stood back and let my heart tell me whether this had strengthened the growing sense of life in the temple, or diminished it. If diminished, I tried the rock again in another place.

My dream is that the whole Earth will be full of “forest temples” of one kind or another, that all of us precious human beings will sing liturgies with the birds and flowers, that, as all prison camps, all wars, all revolutions mercifully come to an end, we'll move together slowly and beautifully with the wind and sun and sky, and the clouds and the trees, as a kind of dance to our heavenly Father.

Who am I to dream like this? Nobody, really—just some kum-ba-yah American nothing-poet with a one-track mind.

But I think the ancient Hebrew prophets dreamed of something like this, too; and I think our Messiah also, when he poured out his life for us, and his body fell to Earth like a seed (Jn 12:24), when it blossomed forth from his tomb again, becoming the root of a new creation—I think something like this will be included.

In Isaiah's vision of the Last Day—the end of history, the end of war and oppression, when the fiery, life-giving presence of God rushes back in its fullness to heal Earth and all her inhabitants of their wounds forever—one of the signs of its coming will be that the places we've made into dry wastelands will become gardens, and our gardens will become as vast as forests:

Will it not be just a very little while

before Lebanon turns into a garden,

and a garden will seem like a forest?

In that day the deaf will hear words of a book,

and out of gloom and darkness

the eyes of the blind will see.

The meek will add to their joy in Adonai,

and the needy of humanity will rejoice in the Holy One of Israel.

For the ruthless ones will come to an end...

(Is. 29:17-20)

Those unable to hear the voice of God gushing forth from all things will hear it again; those unable to see the presence of God shining forth from all things will see it again; those driven into poverty by the ruthless ones of Earth will rejoice again, having all the abundance they'll ever need all around them, at their fingertips; everywhere you look will be a garden, because gardens will cover the Earth, like the great forests of old—in other words, the whole Earth will become a vast and total Eden:

For the palace will be abandoned;

the bustling city will be deserted;

the citadel and watchtower will become a wasteland forever,

a delight of wild donkeys,

a pasture for flocks,

until the Ru'ach [breath-wind] is poured out on us from on high,

and the desert becomes a garden,

and a garden seems like a forest.

Then justice will dwell in the wilderness,

and righteousness abide in the garden.

The result of righteousness will be shalom

and the effect of righteousness will be quietness and confidence forever.

My people will live in a peaceful place,

in secure dwellings,

quiet resting places...

(Is. 32:14-18)

Palaces, citadels, watchtowers, the frenetic rush of the city—all that will crumble, becoming grass and ruins, green pasture for the milk-white sheep of the future. The holy breath-wind of God will cascade down from the sky, a cool breeze, a new life. The desert will turn green and fragrant, gardens and orchards will become as vast and thick and wild as forests, full of life. Both the true wildernesses, overseen by God alone, and also the forest-like gardens cultivated by men and women, will be characterized by righteousness (right-relationship) and justice (harmony with God's way of life, as expressed by Torah). The result of this will be shalom—quietness, peace, serenity, confidence, and Sabbath rest.

And then everything we say, everything we do, will be liturgical—said and done harmoniously together, as a way of praising the Father of all things.

How lovely! But how do we work towards this future reality? How do we go out there and get our heads together and, you know, actually make that happen?

The question is an understandable but distorted one. We live in an age where everything's simultaneously on fire: Earth's rainforests are being swallowed by machines for profit as usual; whole ecosystems are collapsing; all bodies everywhere—trees, seabirds, dolphins, and precious human beings, et cetera—are riven with microplastics and radioactive fallout; millions of Third World children live in and among vast mountains of First World trash, scavenging for their survival; the wretched of the Earth—billions of them—must somehow do without reliable access to clean drinking water, while the ultrarich build luxury bunkers for themselves in anticipation of humanity's first and last atomic war—and so on and so forth; you've heard it all so many times before.

What many of us were trained in school to believe—that we can put our heads together and “make the world a better place”—and, in fact, that our worth as people is found precisely in the extent to which we do so—has turned out to be a delusion, and far too much for any of us lost children to bear.

To quote some forgotten internet bulletin-board genius of my college years:

The universe will not be controlled by the likes of us.

We are not going to build utopia, biblical or otherwise; we are not going to go out there and grab the eschatological vision of the prophets by the horns and wrangle it into existence.

Sisyphus is busy dropping his rock again, and we're not even Sisyphus, who himself isn't even strong enough—we're more like ants on his mountain, who, as the rock cartwheels down the precipice, can either get out of the way, or get crushed—or, more likely, get out of the way, and still get crushed.

Or, to switch from a pagan register back into a Christian one: History is a cross for us to die on, that's all—so let's pick it up and get cracking, my friends; I hear the birds are always singing on Golgotha...

Which, for a Christian, is neither a defeatist nor a despairing attitude—just a realistic one. Our king of the lilies of the field, Yeshua, didn’t fix Roman-occupied Palestine, in which parasitic commercialization was busy uprooting the poor from their land and throwing them out onto the curb, like trash, to die as beggars—whether through various fundraising initiatives or awareness campaigns, or through direct confrontation with the Powers in the usual way.

Rather, Look closely at the lilies of the field, he said, Not even the all-time richest king, Solomon, was dressed so beautifully as they, and look closely at the birds of the air—they have nothing, either, yet our Heavenly Father takes care of their daily needs, also (cf. Mt. 6:25-34). And he lived this way in communion with a very, very, small band of followers—with radical, childlike trust, in a state of perpetual Sabbath rest, in the arms of the Father—even to the point of letting himself be executed, without complaint, without bitterness or hatred, having been falsely accused of insurrection.

That is to say, instead of “making the world a better place”—arguably, it has become much, much worse in the last two thousand years—Yeshua came bearing another world in his heart—deeply rooted in Eden, the world his Father made in the beginning—which he planted in our fallen world like a seed, by living and dying for us in our world, with eyes and arms open to all its brutality and ugliness.

His “work” in our world was rest—Sabbath rest, childlike trust in the Father, to the point of death—and now this new world of his grows like flowers from the concrete of the old one (to borrow an image from Tupac Shakur's poetry) and will never stop growing, no matter how bad things get (cf. Lk 13:18-20).

And although it may seem like enormous leap, and it probably is, this is where I think of a moment of great awakening in the life of the patriarch Jacob, renamed “Israel” only a few verses later and made the root from which the whole people of God would grow:

He happened upon a certain place and spent the night there, for the sun had set. So he took one of the stones from the place and put it by his head and lay down in that place. He dreamed: All of a sudden, there was a flight of steps set up on the earth and its top reaching to the heavens—and behold, angels of God going up and down on it! Surprisingly, Adonai was standing on top of it and he said, “I am Adonai, the God of your father Abraham and the God of Isaac. The land on which you lie, I will give it to you and to your seed. Your seed will be as the dust of the land, and you will burst forth to the west and to the east and to the north and to the south... Jacob woke up from his sleep and said, “Undoubtedly, Adonai is in this place—and I was unaware.” So he was afraid and said, “How fearsome this place is! This is none other than the House of God—this must be the gate of heaven!” (Gen. 28:11-17)

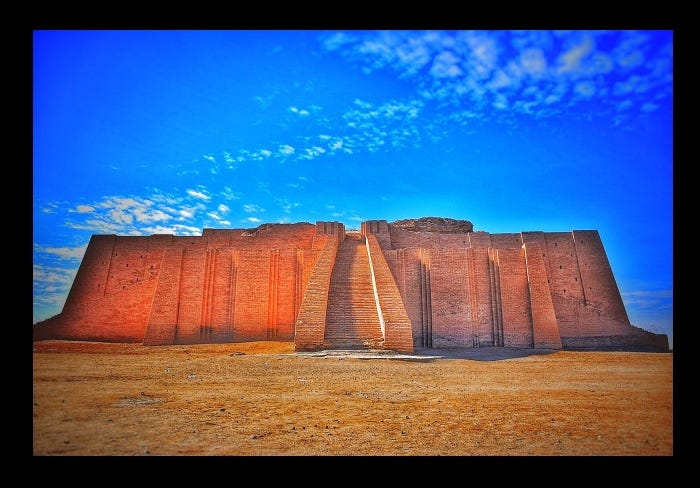

As Robert Alter comments on his own translation of this passage , the word usually translated “ladder” (sullam) is more properly “ramp”—a flight of steps, specifically of the kind that would run up the front of an ancient Mesopotamian ziggurat, like this one:

And there's another allusion to a ziggurat as well, the one in the center of Babylon—what the prophets derided as a tower of “confusion” (babel in Hebrew). The word Babylon is from the Akkadian, bab-ilim, or “gateway of the gods.” The visionary kings of Babylon saw their city as a portal to heaven, its central ziggurat as a stairway to the gods. This means that when Jacob dreamed of a ramp emanating from his heart as his body lay on the ground, sleeping, his exclamation upon waking again that “This must be the gate of heaven” was another way of saying: This is the true Babylon—what Babylon aspires to become in its spiritual blindness, but never will.

Thus, the prophets of Genesis were bringing forth an essential contrast between the hidden, Sabbath counterculture of the Hebrews, and the mainstream culture of those in power: On the one hand, the highly articulated social pyramid of Babylon, from the top of which its great kings orchestrated the labor of thousands of people, transformed into mere parts of a human machine—such that, through the blood, sweat, and tears of these expendable bodies, a vast monument of sun-dried bricks rose up in the air and conquered heaven, as a feat of engineering. On the other hand, the children of God's “ziggurat of the heart” emerging simply by picking out one stone, then lying down in the wilderness and going to sleep—an image of Sabbath rest.

On the run from his brother, alone in the wilderness, without shelter, without city walls, without protection from harsh weather or wild jackals or violent men, Jacob lay down on the ground in a spirit of radical, childlike trust, and a new world came down to him, unexpected—no need for the utopian hustle, no need for anxious striving and technological control.

In the vision of the biblical prophets, we cannot climb our way to paradise—and there is no need to do this, either: Just rest—just lay down, as it were, and rest on the Earth, without complaint, without fear, trusting in the Eternal One who made both the Earth and us, for his own imperishable reasons.

And what comes of this is the tree-like community of God, rooted in the Earth: “The land on which you lie, I will give it to you and to your seed. Your seed will be as the dust of the land, and you will burst forth to the west and to the east and to the north and to the south”—like a burgeoning tree, rooted forever.

This is the same deep pattern that Yeshua, the root of his own New Israel, fulfilled in his own life and teachings:

Unless a grain of wheat falls to the earth and dies, it remains alone, but if it dies, it produces much fruit... (Jn. 12:24).

And likewise:

What is the kingdom of God like? To what shall I compare it? It is like a mustard seed, which a man took and dropped into his own garden. It grew and became a tree, and the birds of the air nested in its branches... (Lk. 13:18-20)

And especially also:

The kingdom of God is like when a man spreads seed on the soil and falls asleep at night and gets up by day, and the seed sprouts and grows—he himself knows not how. By itself, the Earth brings forth a crop—first the blade, then the head, then the full grain in the head... (Mk. 4:26-28)

Certainly we are invited to express our human ingenuity, creativity, and power alongside God's own ingenuity, creativity, and power, as he transfigures our broken world in secret. Sabbath rest is not the same thing as the fatalism, defeatism, or the unimaginative, self-regarding laziness from which so many of us suffer in this age of everywhere-nihilism. In the third parable above, nothing happens until a man broadcasts seed on the soil—so there is a place for man's action and initiative, for his own little ideas, like agriculture, howsoever they may represent a departure from God's original ideas, like Eden (which, after all, was a forest, not a tilled field).

But once the man drops his seeds, he just goes along with the cycles of nature, without worry: When the sun rises, he rises, too; when the sun sets, he goes to sleep as usual; meanwhile, the seeds sprout and grow, he knows not how— “By itself, the Earth brings forth a crop”—the hidden and humble, quiet and ultimately mysterious actions of the Creator take over, building something in secret which the man cannot—which we ourselves still cannot, in spite of our pretensions: a living organism, whole and entire at every stage of its beautiful unfolding: “First the blade, then the head, then the full grain in the head...”

Of course, this is a parable, not a farming lecture on the obvious. But the kingdom of God Yeshua describes in the parable is indeed a living organism, not a machine or a monument; after all, it's biological imagery that's most pervasive in Yeshua's parables, not mechanical or monumental ones, and this must be telling us something—I think so, anyway.

God's radical kingdom cannot be constructed following a blueprint; it cannot be assembled by semi-autonomous swarms of nanobots, no matter how intelligent. It cannot be mapped out as a political program; it cannot be encapsulated by lists of priorities and values; it cannot be consciously organized in any way. All that is human, all-too-human history in the usual sense—little more than building ziggurats, only to watch them vanish under the sands of time. No: As a living organism, it is and always will be beyond the human mind and its dreams of technological control.

As I say, in the story of the garden of Eden, Adam and Eve are co-creators with God, but neither co-powerful nor co-wise: We can, and actually we really need to, participate in God's creativity activity: To express our godlike creativity, to expend our boundless energy reshaping the Earth as its gardeners and caretakers is exactly how we flourish as human beings made in his image: “Then Adonai Elohim took the man and gave him rest in the Garden of Eden in order to cultivate and watch over it” (Gen. 2:15).

But we must do this with supreme humility and sobriety, ever mindful of the difference between ourselves and God—of the rightful inequality that exists, and must always exist, between the Fountainhead of Life himself, and us, his hardscrabble creatures feeling our way through the darkness.

Our creativity is rooted in God's own, and cannot imagine itself as autonomous without dire consequences, as the last twelve thousand years have shown, particularly the last couple hundred. Moreover, our creative action in the world must be sensitive to, and in harmony with, God's own creative actions, which will always outweigh ours by a factor of infinity: It's for us to drop seeds and go to sleep; it's for God to create new life where all seems dead and barren.

Or, if all that sounds too religious, here's how Lewis Mumford puts it in the first volume of his Myth of the Machine:

Man's own nature has been constantly fed and formed by the complex activities and interchanges and self-transformations that go on within all organisms; and neither his nature nor his culture can be abstracted from the great diversity of habitats he has explored, with their different geological formations, their different mantles of vegetation, their diverse groupings of animals, birds, fish, insects, bacteria, amid constantly changing climatic conditions. Man's life would be profoundly different if mammals and plants had not evolved together, if trees and grasses had not taken possession of the surface of the Earth, if flowering plants and plumed birds, tumbling clouds and vivid sunsets, towering mountains, boundless oceans, starry skies had not captivated his imagination and awakened his mind...Long before any richness of culture had been achieved, nature had provided man with its own master model of inexhaustible creativity, whereby randomness gave way to organization, and organization gradually embodied purpose and significance. This creativity is its own reason for existence and its own reward… ...Unfortunately these ideas are foreign to our present machine-dominated culture. A contemporary geographer, already living in his imagination on an artificial asteroid, has observed: “There is no inherit merit in a tree, a blade of grass, a flowing stream, or a good soil profile; if in a million years our descendants inhabit a planet of rock, air, ocean, and space ships, it would still be a world of nature.” In the light of natural history no statement could be more preposterous. The merit of all the original natural components that this geographer so cavalierly dismisses is precisely that, in their immensely varied totality, they have helped to create man...Man's humanity is itself a special kind of efflorescence brought about by the favorable conditions under which countless other organisms have taken form and reproduced...The student who asked Dr. Loren Eiseley why man, with his present capacity to create automatic machines and synthetic foods, should not do away with nature entirely, did not realize that, like the geographer I have quoted, he was fatuously cutting the ground from his own feet...

Man, who is, in Mumford's view, a special kind of flower that emerges from the Earth when conditions are right, bears within himself the creativity which made those conditions right in the first place—so, he cannot uproot himself from Earth and pretend to create another, better world in the sky, without thereby destroying his own creativity in the process.

But we can know that this is true, and accept that this is true, and feel deep anguish in our hearts, knowing that this is true, and it still not matter—and we can find others who know that this is true, and accept that this is true, and feel our own deep anguish with us—and our efforts can still come to nothing in the end.

Something more than a common political cause binding us together is needed—something that transforms the depths of the human heart, aligning it with the Creator's great cosmic dance, in ways that the mind can never fully understand—while also ushering the cosmos itself closer and closer to our own hearts, in the reciprocal movement of love. This is what I call the forest liturgy—which already exists, we don’t have to create it—the forest liturgy on which we're slowly and mysteriously converging at the end of time:

For the palace will be abandoned;

the bustling city will be deserted;

the citadel and watchtower will become a wasteland forever,

a delight of wild donkeys,

a pasture for flocks,

until the breath-wind of God is poured out on us from on high,

and the desert becomes a garden,

and a garden seems like a forest.

Then justice will dwell in the wilderness,

and righteousness abide in the garden.

The result of righteousness will be shalom

and the effect of righteousness will be quietness and confidence forever.

My people will live in a peaceful place,

in secure dwellings,

quiet resting places...

(Is. 32:14-18)

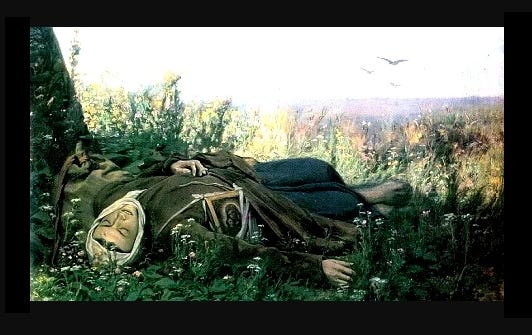

—and this is what Father Pavel Gruzdev and so many others tasted, in beautiful glimpses, when they served the Divine Liturgy in the forest as prisoners of the Soviets before dying. And this is what I think about as I move a boulder here, move a boulder there, throwing lupine and milkweed seeds all around as I work on our little Orthodox temple in the forest, until I, too, shall pass away. And this is what the Orthodox pilgrim below is dreaming about in her beautiful meadow of wildflowers—that's how I like to think of her, anyway.

love,

graham

This is beautiful, Graham, and I’m looking forward to reading where the “way of the forest” takes you.

I’m on a not so dissimilar path, on some acres in rural Montana, groping along, making the turn, something like a secular hesychasm or asceticism the intention if not yet the reality. I’m not one that thinks the horrifying persecutions that the believers in Soviet Russia and Eastern Europe suffered before disappearing into the catacombs and forests is coming to America. Not in a materially corresponding way. That said, I do recognize that capitalism such as it is practiced here, is as much a cult as bolshevism was, a fraud religion, a hoax salvation, and it is bearing down with wicked resolve now. The spiritual intention of each system however seems to me indistinguishable, the destruction of our reaching towards eternity with every portion and in every moment of our lives here in this world, making of it a part time pursuit (at best) rather than the breath of life. Thus, it is best to vanish as much as possible and set up camp somewhere away from capitalism’s centers, in the forests, the caves, the wildernesses (or what’s left of them, they are largely symbolic after the mad rush of the machine over the last hundred or so years). And there fashion our faith and our reaching towards eternity as intimately and profoundly as we can and as the grace of God allows.

It has been much too long since I laid on the ground to sleep. Oh Lord restore my trust in Your Goodness, Amen!