“Outside these utopias and dystopias is the real earth where plants still grow, pots simmer on stoves, soil regenerates, spring arrives, rain falls, and people speak to each other and work the land.”

— Dark Mountain, issue 23

I met a Somali woman at the playground who looked at me like I was a guru or a prophet when I told her I didn't have a smartphone—that our children weren't allowed to have screens, either.

She was amazed. And also envious and melancholic, and also wistful. “Oh my god you're so lucky,” she said in a hushed voice, sighing and looking away.

And to be clear, I had just told her about something we didn't have, not something that we did. But our not having it was a kind of luminous treasure in her eyes, a beautiful gap—she wanted one, too.

About her youngest son—who was kind of playing with my children at the playground, but not really—she said, “He doesn't scream when he's tired, or hungry, or thirsty, or lonely, nothing: He only screams when he can't have his phone.”

The woman seemed really, really tired.

And her son—maybe a five or six year old—seemed really confused about where he was.

I tried to be encouraging. “Sometimes I pray for a gigantic solar flare to erupt,” I said. “Sometimes I dream of giant waves of energy smashing down from the sun, turning all of our screens into only so much silicon and plastic rubble.”

When I said that, the woman's shoulders relaxed and she was able to smile again. “Yeah,” she said, nodding.

Then we looked past the trees, past the clouds. We daydreamed of catastrophes falling from the sky, of an entire way of life evaporating in an instant, being demolished by the invisible angels of the heliosphere.

And then it was time for her to take her son to masjid. “Nice to meet you!” she called cheerfully as she left, head still full of smiles.

Because sometimes all you need is a good apocalypse.

At the end of his book, The Technological Society, published in 1964, Jacques Ellul said

The human race is beginning confusedly to understand at last that it is living in a new and unfamiliar universe....Enclosed within his artificial creation, man finds that there is “no exit”; that he cannot pierce the shell of technology to find again the ancient milieu to which he was adapted for hundreds of thousands of years.

For me, the smartphone (which so afflicted my friend) symbolizes, and actualizes, this inescapable shell of technology with a special clarity, because it goes with us wherever we go, as a kind of second self.

Or, more cynically, because it's a tracking device that's fun to play with.

Whatever might be beautiful in the world—a flower, a child laughing—we hold the screen up, in the place where we would have originally upheld our own faces, eclipsing them with pixels, dragging them into the stream of digital memories, lest they fall away into nothing—as if we ourselves, in our bodies, are becoming nothing.

Whatever we might want to think or dream about, whoever we might want to see or talk to: Let it all happen through the screen—this screen which, even if dark for now, must remain resting on our thighs or, at its most distant, the same distance as a glass of water, in case it lights up again, awakening as a conduit for gushes of digital life streaming down from a nirvanic Elsewhere ruled by the embryonic gods of the future.

Screen addiction is chemically the same as drug addiction, causing the same damage to the brain. Screens amplify suicidal thoughts, also. But, we've somehow painted ourselves into a corner: We can't live without them, because they are, or at least seem to be, the interface between ourselves and the shell of technology in which we apparently must now live.

In some places on Earth, this is literally truer than others. In the realworld AI surveillance dystopia of Xinjiang, China, you have to have a smartphone if you're an ethnic Uighur, because if you don't have one, it means you're obviously some kind of hardcore Wahhabi radical and need to be sent to “Transformation Through Education”—the Xinjiang concentration camps—to be sterilized and beaten into submission.

But if you do have a smartphone, that's how they track you—not only where you go, and when, but also if you listen to scripture on your phone, send scripture verses to others, or listen to sermons or buy a prayer rug or make a religious donation online: Too much religion, and you're off to the camps, brother, joining at least a million others, perhaps even two.

Or, if they don't disappear you, they can still freeze you: Already, if you're tagged as a religious radical, alarms are triggered if you—carrying your phone—try to leave your neighborhood or enter a public space and you'll be arrested. And once Chinese society is entirely cashless, a process already largely complete, it'll be easy for the System to prohibit you from buying food or fuel or clothing or transportation through your smartphone, also.

So in this sense, smartphones for the Uighurs today, and perhaps for the rest of us tomorrow, are like icons of the Roman emperor in the early days of the Christian martyrs: Surrender to the system that the icon represents, by surrendering to the icon, and you gain access to that system and can reap its benefits. Refuse to surrender, though, and the system casts you into the outer darkness—you become a non-person; you fail to exist.

But even people who only imagine they can't live without smartphones, or that they wouldn't want to, feel them as a force from outside, it seems. In a recent survey, 73% of Americans said they would be “happier if they spent less time on their phones”—but they don't spend less time; they spend more.

And one result of this is a kind of collective smartphone sigh, an almost atmospheric smartphone cliché, about wanting to feel more connected through the phone, but only feeling more fragmented than ever, more isolated—everybody and everything drifting farther and farther apart, though we know in our heart of hearts, and can even say aloud sometimes, that it's our technologies of connection themselves that keep us disconnected.

It's as if we believe that rededicating ourselves to the melancholic irony of lament, since it's all we can muster now, should be able to count as some kind of resistance in the eyes of somebody, somewhere—it's as if we're muttering a kind of prayer.

But I don't know who we're praying to when we pray like that.

My little dream is that the church could become a place of Sabbath rest from such addictions. It could be the place, maybe the one place left, where it's possible, or at least becoming possible, to “pierce the shell of technology,” as Ellul says, to “find again the ancient milieu” to which our ancient, God-breathing bodies of clay have always belonged, and always will.

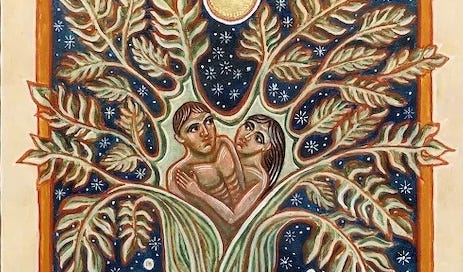

For example: What if what church looked like were an Edenic garden—a whole forest of beautiful, edible plants, like this:

This church does—it’s possible!

And what if to be within the outer walls of church already, and on your way further inward, felt like this:

Or what if church at least didn't do the opposite: What if it didn't enforce the idea that the shell of technology is as real as stones and trees and sun, or even more real, and more permanent and normal, because even more convenient for us, and nice:

But that's what synthesizing liturgical life with the digital nonlife of the screen does, in my (apparently very fringe) view. And that's also what even something as apparently harmless as electrically amplifying the human voice does, shifting its origin from the throat in one's body to faceless speaker boxes scattered elsewhere, in Sherrard's (also very fringe) view:

It is the same with other desecrations: Microphones, for instance, falsifying the living voice and changing the source of sound, are proclamations of counterfeit, self-deceit, and disintegration, of precisely the sins that the liturgy is intended to overcome.

Counterfeit of the human self, self-deception of the human self, disintegration of the human self—it's precisely from these gaping wounds of self-betrayal that the liturgy is intended heal us, says Sherrard:

Ecclesial liturgy and cosmic liturgy reciprocate one another and are interdependent. In this way the action of the liturgy represents and effectuates a transcensus of the fallen state both of human life and of all other created life as well.

The Cosmic Liturgy—the harmonious, cyclical motion of sun, moon, and stars, the beautiful unfolding of herbs, flowers, trees, and clouds in time—manifests God's depths as a communion, as Holy Trinity. It is, if we can put it this way, the Tao of Eden, “the will of the Father done in heaven” that Yeshua taught us to pray would also be done on Earth, among us longlost humans (Mt. 6:10). It's the morning stars singing together (Job 38:7); it's the trees of the forest singing for joy (Ps. 96:12) in the presence of the One.

The Divine Liturgy—and the liturgical life of the church in general—is meant to reflect this Cosmic Liturgy, and also to draw us further into it. And the more deeply integrated within the Cosmic Liturgy we are, the more truly ourselves we can become again, more integrated and whole, because we were planted in Eden to live in harmony with Creation in the first place—both reflecting, and participating in, God's self-harmonious life as a communion of love.

Thus, liturgical life “represents and effectuates,” as Sherrard says, a transcension of our fallen state, which in the vision of Genesis begins with an illicit grasping for the power of God—the knowledge of order and chaos (basically, the knowledge of how to disrupt, exploit, and redirect the harmonies of Creation) and ends in a downward spiral of self-isolation: Adam and Eve hiding from the Fountainhead of life, putting on fig leaves, pretending to be the trees of Eden, then animal skins, trying to disappear—then building cities, hiding behind stone walls, too, hiding behind the whole technological artifice of civilization as a kind of counter-Eden, in which the human self—symbolized as Cain, the brother-murderer—simply wanders around, afraid of life, and unable to see his Creator, who is present everywhere, and fills everything.

All technology should be seen against this prophetic backstory, and evaluated from within it—but especially, I think, technologies of simulation. For, just as the Ru'ach—the Spirit, the Breath-Wind of God—is “everywhere present, filling all things,” making all things one in the Cosmic Liturgy, so also we (in whom faint memories of God still linger) wish in our counter-Eden to become omnipresent—to overcome the barriers of time and space—not through God's intimate Breath, but through our own technological prowess.

Perhaps microphones and speakers are a trivial example of this (Sherrard didn't think so): We can make our voices come from elsewhere than our own human bodies—we can make ourselves heard from sprawled out, technological bodies that can exist in many different places at once (wherever we decide to place the speakers). Live streaming is more serious than that—it's the same idea, greatly amplified: I can be heard, but also now seen, from a fragmented, technological body spreading literally over the entire Earth, and above the Earth, in satellites in space.

But the effect of this is you can hear and see me, without being in my human presence—in the presence of my actual self—my body, my material roots in the Cosmic Liturgy. Which might be OK (but not great) for casual conversation (we communicate subtly through body language, as well as through the magnetic fields of the heart, so much that is important is lost)—but it's the opposite of true communion.

And so, from a certain naive, childlike point of view, the liturgy is the last place one would expect simulation technologies like this to become entrenched. But one does find them entrenched exactly there—even more so, now that live streaming is apparently here to say.

But to the extent the church—like the world system at large—is a also place of “no exit” from the technological shell, then it's in danger of becoming a visionary ruins—a place of dreams and ideas, a wonderland of metaphysical correctness, as divorced from physical experience—an “all head, no body” religion, Borge's infinite library as a bunker for the pretend wars of Us against Them, as opposed to the real wars of reality against self-deception.

Which is not to say blessed are the anarcho-primitivists, dressed in flowers, for they shall inherit the church. Actually, technology of a certain kind is at the heart of our Christian life together (analog, not digital, technology; humanizing, harmony-seeking technology powered by the human body and the shining sun).

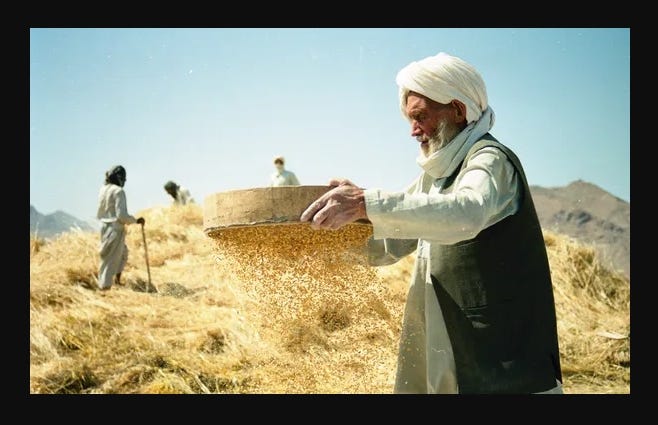

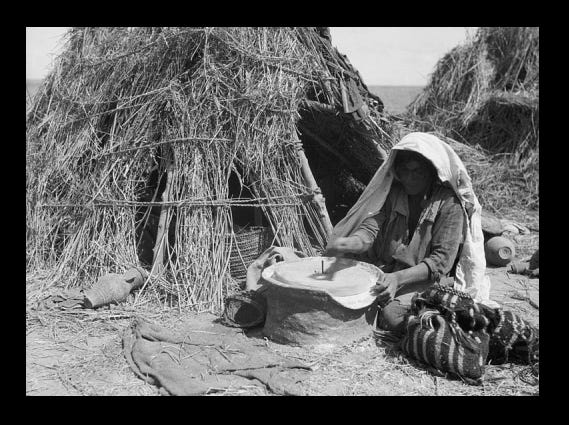

Bread is grass, wine is rainwater—but a lot of things have to happen for grass and rain to become bread and wine as we experience them in the Eucharist: The seeds of the grass have to be milled into flour, mixed with water, salt, and yeast, and placed inside a fire; the rainwater has to be drunk by the roots of grapevines, filled with carbohydrates made by the action of photosynthesis, then crushed again from the grapes and fermented by yeast: These are man's technological creations working harmoniously with the creations of God, co-creating the means of fellowship between God and man.

Still, bread is basically just grass, and wine is basically just rain—but by being “just grass” and “just rain,” they include the whole Earth: When the priest holds the bread and the wine above the altar and sings in a loud voice—

Thine own of Thine own

We offer unto Thee

On behalf of all, and for all

—it is a man whose body is fashioned from all the elements of the Earth, offering up the whole Earth to the Creator, on behalf of all the inhabitants of Earth, receiving the self-emptying life of God in return.

Triticum grass (wheat), like all plants, exchanges gases with the atmosphere, breathing in what animals breathe out, and breathing out what they breathe in. The respiratory systems of all plants and animals on Earth are intertwined—triticum could not exist without the breath of dolphins, or of human beings, and vice versa.

And wheat is pollinated by the wind, also—so what makes the wind blow? The structure of the whole universe, basically, in the forms of gravity and sunlight: The interaction of sunlight with the surface of the Earth causes differences in air temperature; in Earth’s gravity field, these become differences in air pressure, so that toppling stacks of air, constantly seeking equilibrium and rest, are always cresting like waves into somewhere else, carrying with them seeds, pollen, and nutrient-rich dust—that which makes the wheat grow is also that which makes thunderstorms and hurricanes, and also black holes and stars.

And so when we eat bread and drink wine together, we're eating and drinking sunlight and gravity, wind and rain—even the ebb and flow of tectonic plates, the carbon cycle, the rock cycle, and the star cycle; we're eating and drinking everything—the whole cosmos—revealed in the Cross to be an expression of the self-emptying love of Messiah: “This is my body, broken for you; this is my blood, shed for your life, and the life of all things.”

And we do this in a way that affirms our own human place within the cosmos: Without agriculture, without fermentation, without fire—without the touch of human thought, human creation—there would be no bread or wine, no Eucharist, and also no self-identification of Yeshua with bread and wine as his body and blood, poured out for the life of the world.

In this sense, the Eucharist is human technology, at the scale of the human body, integrated with the body of God. But it has to be human technology, at the scale of the human body, or else it's not the Eucharist, says Sherrard:

When Christ said, “This is My Body”—that bread is His body—He was saying it in the context of a cosmic liturgy of which the whole process represented by the tilling of the earth, the sowing and then the nurturing, harvesting, threshing, milling, kneading, and baking of the wheat from which the bread is made constitutes the epitome. In this process all the elements—earth, water, air, fire—are involved, as is human participation in the most intimate physical sense....To take the bread out of the context of the cosmic liturgy of which it is the epitome and consummation is just the same as to remove the Eucharist from the ecclesial liturgy of which it is the epitome and consummation. Removed from that context it ceases to be the bread of which Christ said, “This is My Body.”

When Messiah said of the bread, “This is my body,” he said this in an age in which bread could only be made with the human body: Wheat was planted by scattering seeds with the human hand; harvesting it was done by human hand, also with a scythe; threshing and milling were tasks for the human body, also, perhaps with the help of animals and the wind; and the most intimate part of the process, kneading the dough, was of course done by two human hands—after which the dough was placed by hand in a beehive-shaped clay oven, which even a child could make with her own little hands.

Not just the loaf, as an apparently self-existent object in the world, was Messiah's body; the loaf as a network of self-emptying human relationships—relationships with one another and the Earth, through human touch—this was and is Messiah's cosmic body, and always will be.

Which is a far cry from what's becoming of all this in the age of the Machine! The wafer factory which now controls 80% of the communion wafer market boasts on its website that “throughout the entire production process the breads remain untouched by human hands” (emphasis mine)—which is really communion as a kind of anti-communion, atomic wafers placed on the lips of atomized human beings by conveyor belts instead of priests (but they're only $23.70 for a pack of 1000 on Amazon, if you want to buy some).

In the Orthodox Church, we're still using loaves of bread that still have to be lovingly made by human hands, by people in our own parishes, thank God. But for those of us simulating participation in our Divine Liturgies from afar, the shifting digital images of that homemade bread are more abstracted from reality than any manufactured wafer would have been anyway, and so I'm not so much interested in who's Orthodox, and who's not, as in whose commitment to an earthy, embodied life of table fellowship and giving thanks to the Lord of nature helps them recognize an antihuman technology when they see one, and sidestep it for the sake of deeper communion.

Wherever you are, whoever you are, brothers and sisters, I wonder if you feel as I do that a lot of distortions in relationship are corrected when you correct the corresponding distortions in scale. After all, the original context of the Eucharist was the home! At its best, an expansive and secure home—for example, the Roman villa, as a microcosm of the universe, with its open-air gardens and refreshing pools of rainwater in its center—but still, the home: The scale of architecture and slow pattern of intimate, communal life which most nourishes the sense that yes, on Earth, we humans are at home.

To be truly at home, though, is “Every man under his own vine, his own fig tree” (Micah 4:4)—to be immersed in human-scale, human-nourishing gardens, where the cycles of growth and decay in nature, the cycles of sunlight and wind and rain, can be grasped in the cycles of one's own human body—where one can literally touch the Earth with one's body and, like Adam and Eve, who sprang from the dust of Eden like flowers themselves, participate directly in God's life-sustaining activities, as “animals who have received the vocation to become God” (Saint Basil of Caesarea). For that, we don't need vast homesteads in the countryside (though these are nice)—just a determination to touch the Earth and plant things, says Ron Finley, who for the last thirteen years has been transforming the vacant lots, sidewalks, and traffic medians of South Central LA, of all places, into a lush paradise of local food resilience—something which should be as natural as breathing for all Eucharistic communities, but somehow isn’t yet:

If home in that sense—quiet, human-scale places surrounded by gardens in which humans work closely with one another, with their own hands—if that were the physical and social environment in which much of our liturgical life took place, I imagine technologies like world-connected digital eyes allowing anyone from anywhere to watch from his or her own religion booth would be more widely and more immediately recognized as an alienating, counterproductive factor—something to be expelled, not welcomed as a convenience.

This is what I was thinking about when I began this essay series with a quote from the second century pagan critic, Celsus, deriding the Christians of his time:

They cannot tolerate temples, altars, or images. In this they are like the Scythians, the nomadic tribes of Libya, the Seres who worship no god, and some other of the most barbarous and impious nations in the world.

But the ancient Christians didn't need temples, because they met in homes; also, because “the whole universe is God's temple,” as Origen said later in his response to Celsus. And they didn't need altars, either, because they gathered around a table—of the normal, domestic kind—or outside, on the grass, if they had no tables, to eat bread and drink wine together as new brothers, sisters, mothers, and fathers to one another and Messiah, becoming day by day his new body on Earth; this was their radical “irreligion,” requiring no priests, no spiritual magic of the usual Roman kind. And they didn't need images, either, because humans gathered like that as a communion of love are already living images of the Living God—so what would you want to pray to pictures for?

This is the kind of “Christian irreligion” it seems it's perhaps time for again: A kind of inner flexibility and resilience and exasperatingly slippery defiance of the spiritually mandatory, as conventionally understood, that can just as well make prostrations on green grass and sing with the birds in a temple of blue sky and dandelions and clouds, as with other people in a temple of wood and stone—especially if that kind of temple has become, or could become, a locus of antihuman control.

My little idea in lieu of digital streaming from afar is to retract to the “irreligious,” human scale of the home—and of course, this is not my idea at all, but simply what we've often returned to as Christians when the catastrophes are real enough to wake us up!

I think first of all of those Orthodox Christians who suffered recently under the Soviet revolutionaries. The ones who could foresee the antihuman madness that others refused to believe would ever come knew it was time to retract the Eucharistic life back to its ancient roots in the home. Bishop Damascene Tsedrik, for example, who wrote this letter to his flock in 1929:

It is not the church buildings that are the Church, but we, the people, are the Church! ...There was a time when Christians did not have temples at all, they recognized each other only by conventional signs. They gathered to perform the most Holy Sacrament at homes, in underground cemeteries, in catacombs, in the wilderness....Believers need to be ever closer to each other. It is necessary for us to join into the closest of alliances on the basis of our single faith, common prayer, and mutual support for each other in the sorrows that have befallen us. It is necessary to unite around the priests known to us in order to recognize through them the grace of Christ in the Holy Sacraments, which, perhaps, will be performed in secret places. Of course, ceremonial services, pretentious choral singing, and loud protodeacons will have to be abandoned, to be replaced by the quiet, concentrated prayer of small groups at home in the most simple of atmospheres, in the most modest of vestments....It’s time, Beloved Ones!

And that's the way of life that many, though of course not all, took up. One collection I love, of lovely—and also painful—reminisces of life together in this Orthodox underground, is called Father Arseny: A Cloud of Witnesses. It's full of beautiful stories—of hardened criminals who encountered Father Arseny somewhere in the gulag archipelago, and later became catacomb priests, and of simple people who just loved one another and kept their heads down as best they could.

One of Father Arseny's spiritual children summed up the whole era like this:

Our community had to lay low, but it lived on in secrecy. We all would pray and read the same chapter from the Gospel. Priests who no longer had a church in which to serve but who had not yet been arrested or exiled used to celebrate joyous liturgies at home.

For the present situation in the West, post-2020, something like this could become part of our path home from the isolation and fragmentation of life within our self-made technological shells: home to the body, home to the Earth, home to one another as brothers and sisters in Messiah.

And instead of waiting for the next crisis (which will come soon enough) we could return home to one another now, and live beautifully and with deep roots—come what may. Our lives as Christians together—while it's still possible—could still be centered around celebrating the Eucharist in the flesh on the day of the sun, in the temple of our local parish. But also, on one evening during the week, we could make a habit of meeting together in separate, smaller groups in the homes of whoever would offer them.

And on these weekday evenings, two very embodied, human-scale, community-nurturing things could happen: One, we could chant and sing the Typika together (an alternative to the Divine Liturgy, for when a priest cannot be present), and two, we could share the table fellowship of a common meal (with all screens banished, as a way to cherish face to face communion).

The set of relations between parishioners, hierarchy, home, and temple would then be something like that of the early days of the Christian movement, before the first persecutions:

Day by day they continued with one mind, spending time at the Temple and breaking bread from house to house. They were sharing meals with gladness and sincerity of heart. (Acts 2:21)

The earliest followers of Messiah still participated in the liturgical life of their fellow Jews, centered on the Temple, while the Temple was still standing—but they also sang hymns and practiced table fellowship in their own homes. This, among other things, built up resilience for when they were eventually expelled from Jerusalem, and their Temple was destroyed: They could continue their Messianic way of life together, more or less uninterrupted by what an outsider would have seen as a series of world-ending cataclysms.

In the same way, if we've already built up a practice of meeting together in our human bodies, at the scale of the human home, and taking care of one another's needs and singing together in the body, then if further lockdowns are imposed, or if church buildings are closed or become otherwise inaccessible, then we can continue our human life together in the body, without resorting to digital technologies of simulated togetherness (likely also the same technologies by which lockdown compliance and access to church would be controlled, if indeed the Xinjiang panopticon is a glimpse of the future, as it looks like it might be).

In times when church life is flowing along normally, our weekly celebration of the Typika together, followed by face to face, openhearted table fellowship without screens, would strengthen our spiritual muscles for singing and prayer, and would help us come to embrace the fact that the liturgy—leitourgia—as its name denotes is indeed the “work of the people,” not a spectacle to be enjoyed from afar—and it would also strengthen our human bonds with one another, which is always sorely needed, no matter how peaceful the world on any given day is or isn't.

And then our priests could slowly make the rounds from home to home, from week to week, participating in our smaller, slower scale of liturgical life with us, guiding and helping us as always. Alternatively, in times of crisis, the priests could make the same slow rounds to the same houses of prayer, to lead us into the fullness of the Divine Liturgy every few weeks or so, as in the days of the Soviet oppression (the transition between normalcy and crisis could be almost seamless, if we wanted it to be).

The homes in which we'd sing the Typika together—and perhaps the Divine Liturgy, if it came to that—would of course have to become temples, too, as all Orthodox homes are meant to be—adorned in icons, beeswax candles, lamps, clay vessels for burning incense, and so on; they'd have to become havens of stability, rest, and beauty, places in harmony with the human heart. But just as the Hebrew Temple was engraved all around with palm branches and open flowers (1 Kings 6:29), pointing to Eden as the true referent of sacred space, so also our temple-homes could be surrounded by beautiful (and also life-sustaining, not just ornamental) gardens, as a way of pointing back to Eden—and also forward:

The bustling city will be deserted;

the citadel and watchtower will become a wasteland forever,

a delight of wild donkeys,

a pasture for flocks,

until the Breath-Wind is poured out on us from on high,

and the desert becomes a garden,

and a garden seems like a forest.

Then justice will dwell in the wilderness,

and righteousness abide in the garden.

The result of righteousness will be shalom

and the effect of righteousness will be quietness and confidence forever.

My people will live in a peaceful place,

in secure dwellings,

quiet resting places... (Is. 32:14-18)

Or, as I'd maybe put it: Every home a temple, every temple a garden, every garden a forest, every forest a home. That's how I read the prophets, anyway: A return together to an archipelago of blossoming temple-homes—unified by a common life together in the main temple—sprawled across the Machine's worldwide oceans of asphalt and concrete—a retraction, when necessary, to quiet resting places enveloped in Edenic gardens from which we'd feed ourselves, and also our suffering neighbors, perhaps even grow our own wheat and grapes by our own human hands, transforming them into bread and wine for the Eucharist with our human hands, also, living as a deeply embodied, Earth-connected communion of love: This could already be a way of living in the age to come—as both a prophetic witness to its arrival, and perhaps also one of the means by which it does so.

I ran into my Somali friend at the playground again today. After salam alaykum, wa ʿalaykumu s-salam, we didn't talk—which was my fault, mostly. It didn't really seem like we could talk about solar flares again; other than that, all I could think of was the things I always and only think of: the birds, the sky, the clouds—how beautiful it all is—but there was no need to say so.

I was relieved when my littlest girl asked me to push her on the swing.

My friend was relieved, too, I think; her head dropped back to her phone, with which she'd been chanting her Qur'an.

The invisible walls between people are real, I guess. It wasn't just her phone and her earbuds—it was our histories and our cultures, too, it was all the ideas in my head: Probably, it actually would take a solar flare—or something at least as catastrophic—to shatter all these shells in which we hide from one another, even though we're all ultimately sons and daughters of God.

I don't actually pray for one, though: I know we're not ready, that people would suffer a lot, probably without much result. We're all so enmeshed within the artificial world of screens, of computation and electron flow—and, of course, I am also.

We are the Machine; the Machine is not other than us. We're Adam and Eve, wearing digital skins, trying to hide—and we really are naked, and we really would be swept away in the onrush of Creation, if that skin were ripped away suddenly, exposing our spiritual wounds, our separation from God.

But also: We're still human beings, still absolutely free as sons and daughters of God to go the way of the Machine, or not. If we're serious about the Eucharistic life, couldn't we also spread across Earth, solar flare or not, as our own quiet little apocalypse, shedding accretions of antihuman technology wherever possible, and sprouting island-like, Eden-like gardens and totally embodied, anti-virtual communities in their place?

Or must we also keep drifting along in the ocean of anesthetizing convenience afforded by the Machine?

And I don't know if, by asking such questions, I'm one of Orthodoxy's faithful sons, or if I'm just one of its treehugging rebel cousins—I really don't know. And I don't know if that's even a relevant question—probably not.

But what I do know is that, wherever we are in our own human bodies, we can gather with other humans there, plant gardens, and pray—and that this is the way of the future.

love,

graham

Love this reflection and thank you for your thoughtfulness! Me and my kids and best friend and some of our friends from church have started doing this...we all have the same intuition you describe. During COVID times we gathered and read the typika because the streaming services felt...cold. At a time when we were so desperate for warmth! We are terrible singers so we learned to laugh at ourselves! Ha! God bless you Graham we are all in this together. Thank you for the encouragement while we are in touch over the wired! Someday probably not too far down the road... people like us will probably withdraw from this corrupt medium of contact. When the time comes, I hope you will keep sending out your writing on paper via the snail mail! The postman will return to his old heroic form! My dearest friend is a rural postman, he'll be a hero in the days ahead! Ha! If there is an option now to receive your writings by mail I would love that option so much! Either way thank you and may God bless you a million blessings!

What is essential is what we have when earthly treasures have been taken from us and all we have is the treasure we found hidden in the field - the kingdom of God which is “righteousness, peace and joy in the Holy Spirit, Romans 14:17, the Spirit of God, the Spirit in the temple of our body and the Spirit found between two or three gathered in His name. But we, so often in our cravenness, find that not enough, and seek solace in the transient. May we exult in the gift of “It is the Spirit that gives life; the flesh is no help at all” John 6:63 and have rivers of living water flowing from our hearts. For “let the one who desires take the water of life without price”