This is the sixth and almost last part of an essay series which takes as its inspiration something Wendell Berry said in The Unsettling of America: “Over and over again, spring after spring, the questing mind, idealist and visionary, must pass through the planting to become nurturer of the real.” Resounding in the background, too, as if across an empty canyon where our hearts used to be, is Vine Deloria's rhetorical question to the sunset of the West: “Can the white man's religion make one final effort to be real?”

I think a book should be written entitled, “The Realism of Orthodoxy and the Romanticism of the Orthodox People.”

— Father Alexander Schmemann, Journals

In this essay, I will make my peace once again with Orthodoxy, and also once again with Platonism, having gone into some dark spaces within, as I do, and come out again, the sun shining again in the grass, as it does, the birds singing outside the window-screen as I type these last words: It has taken a long time to get here, and still, we’re not there yet.

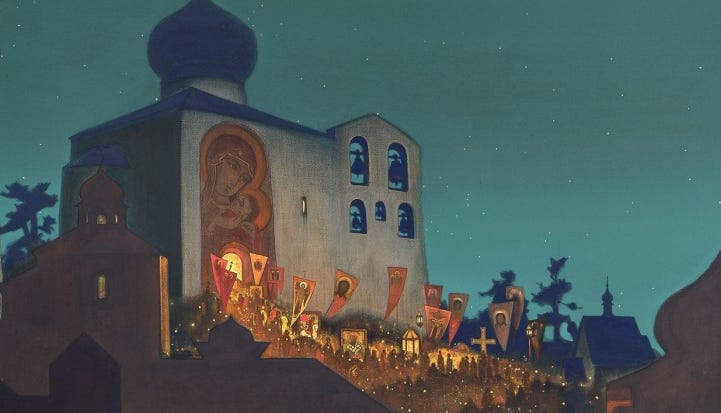

Having encountered Orthodoxy first in the visionary spaces of Dostoevsky’s “Love every leaf” and “Love the animals, love the plants, love everything. If you love everything, you will perceive the divine mystery in things” and “For everything, like the ocean, flows and enters into contact with everything else: touch one place, and you set up a movement at the other end of the world. It may be senseless to beg forgiveness of the birds, but, then, it would be easier for the birds, and for the child, and for every animal if you were yourself more pleasant than you are now. Everything is like an ocean, I tell you. Then you would pray to the birds, too, consumed by a universal love, as though in ecstasy, and ask that they, too, should forgive your sins”—having been in that world, and having been there in the poetic mind alone, flying away from my twenty year old body, the first time my dear friend, Henry, and I went out looking for an Orthodox church, only about forty minutes away from us in North Carolina, what I thought I was looking for in my mind’s eye was something like this:

And though we were pretty sure we had the directions right, and retraced the last parts of our route a couple times just to make sure we hadn’t missed a turn, we ended up not finding what we were looking for, because of course no such place existed in the real world. And so we drove on to Bojangles, which certainly does exist—to the great joy of people who know what I’m talking about when I talk about the glorious existence of Bojangles—and broke our fast with sausage gravy and biscuits.

Turns out, we had the directions exactly right; we knew exactly where we were going. Only, the church itself was meeting in a rented space buried in the bleakness of that quintessentially American way of envisioning hell way ahead of time, the strip mall, and so, although we knew exactly where we were going, we had no idea we were going there.

The beauty of American strip malls, if there is one, is that American strip malls do only one thing, which is to sit there as American strip malls, without transcendence. They are what the disenchanted world looks like when it has decided to look unapologetically disenchanted, going out for a permanent smoke in the parking lot of history: The white parking stripes painted on the flatness of black asphalt, stripped of mythological content, mean If you put your car here, it will fit. The purple neon Kinko’s signs attached to the faux-limestone cement facade mean If you photocopy pieces of paper here, you will have more copies of those exact papers. And the Palm Beach Tans, with their iconographic signage of palm trees abstracted from literally the rest of the universe (and the American strip mall is really the one and only context in which it actually makes sense to call signs ‘signage,’ nominalizing something that’s already a noun, as if the vaguely verbescent act of self-nominalization somehow makes up for a total lack of meaning)—what the Palm Beach Tan ‘signage’ is really saying, from the concrete citadel of American strip malls, is If we spray your skin with bronzers, then your skin will in fact look more bronze.

That an Orthodox church would try to be the Orthodox church in the heart of American darkness has an earthy beauty to it, and also a kind of earthy swagger: Daniel-in- the-lions’-den stuff, sitting serenely with seven fearsome kings of the jungle; the three holy children of Babylon, drinking gin and tonics in the fiery furnace.

And even if that particular parish turned out to have been a total disaster—or, much more stressful for people with minds like the mind I have, a permanently ambiguous mix of disaster and transcendence—the attempt itself would have been beautiful, regardless. Because, leaving the sidewalk, you would have gone through the glass double doors, which instead of ACE HARDWARE & PAINT stenciled in white paint as you enter, would have said ALL SAINTS ORTHODOX CHURCH or something equally inexplicable and suddenly you would have been walking through clouds of incense, and vibrating golden walls of Byzantine chant, and the honey-smell and flickering light of beeswax candles, and haloed visions of the human face in communion with the sun.

And the words people would have been singing, if you could make them out—and you couldn’t, really—would have seemed to have been converging on a kind of infinite love that can’t be expressed in human words, but the people crammed into this little outpost of heaven sure as hell were going to try it anyway, as you would have found out again and again over the next hour and a half of standing and singing, the priest singing “Again and again let us complete our prayer to the Lord,” meaning, it turns out, that you were absolutely nowhere near the completion of anyone’s prayers to the Lord, not even close—you would have barely just begun.

And actually, the more you now stand there, the more it dawns on you that your life itself, the life of the whole universe, has barely even begun, whatever that means—and, simultaneously, that all of it could scarcely ever come to an end, and that this forever non-completion of singing to the Lord is, and always has been, our flowerlike unfolding home...

I have a brilliant synesthesiac friend who has theories about this deep time-expansion thing that happens in the Divine Liturgy: He says breathing the billowing clouds of incense at church is like being high up inside the warm and dry cavity of a vast tree again, from fifty million years ago, as the safest place in a world of ape-eaters, our abundant home-tree overflowing with the sweet honey-sunlight of beehives from all candles, dudes humming the low drone notes of the chants, all of us apes nesting in the sunlit memory spaces of some post-Cambrian primate psychedelia...

I have another brilliant friend who lives his life high up inside that ancient tree, which is to say deep in his own heart, face now shining in the sun, and he says, “I have no wisdom/advice/perspective on Orthodoxy or any other -doxy.” He says he just goes and looks at the icons and prays and chants “from the same state of absolute stillness I have felt in the few times I was lucky enough to stand completely still in an old-growth forest.”

And he says:

Whenever I hear some Orthodox person talking about "true church" or "apostolic succession" or "primary access" or that other self-righteous jargon, it literally registers like little soundless zooming blips in my periphery. It means literally nothing to me. It snags literally none of my attention. I have zero pause or hangups or reflection to offer any of that. It feels like I'm in an art gallery looking transfixed at a painting that has utterly sucked me in and there are these faint voices of idealists, critics, commentators way out in my periphery mumbling art school jargon and it has nothing whatsoever to do with the transcendent encounter I'm having.

He says—and you should know he’s had a difficult life, and that he’s been through a lot of pain—he says, “God feels more real than It/He/She/They/All has probably ever felt to me. So I guess I just feel quiet and grateful.” And he says:

This whole time I have been a foot off the ground, slightly angled forward and floating forward. Being lightly pulled toward light...it has nothing whatsoever, in my felt experience, to do with a building or a priest or a patriarch or vestments or anything material...beyond the purity that seems to be floating through me from the Presence I am feeling in my life in general, in the space before the icons, and the prayers and chants and incense…. And I feel this profound intuition/clarity which simply floats up inside me when dealing with people. Just deep space-like stillness, quiet and floating suspension with a light-saturated/transparency nature to the world...

I love you, brother—there’s so much beauty in that, and I can see so much healing. And there’s also (my words, not his) so much earthy swagger in a spiritual counterculture like that, that aims to cultivate reunion with the Presence, from deep inside an anti-spiritual, disembodying cultural mainstream that does everything possible to shatter it.

Speaking of collapsing worlds, the Peloponnesian War was the catastrophic self-implosion of an ancient Greek world that seemed to hold in its golden hands a golden future. But that future slipped away; Athens and Sparta, which had, to eternal glory, joined together to fight off the Persian empire, turned against each other in an on-again, off-again brutal slog that would last for over twenty years, leaving everything in ruins.

And what I think helps me understand the anxiety to transcend nature of the philosophers who were to emerge in the aftermath, was that the war was brother fighting against brother for the non-entities of wealth, power, and imperishable glory—but it was also a war of man fighting against Mother Nature, and man losing both shamefully and catastrophically: The plague of Athens wiped out a quarter of the population, refugees of the war crowding together inside its broken walls, drinking its undrinkable water, clawing at one another like the wounded animals that they were, clamoring their way back into the womb of an Athenian Golden Age, the last idiotic barbarity of which was the democratic execution of Socrates.

In the traumatic ruins of all this, Plato came forward to envision another world—a perfect world that could become embodied in this one, as his utopian Republic. And, more than in that city yet to dawn, his new world had already been concretely but elliptically revealed in the life of a man who was executed by the old one—who had, in fact, died in a beautiful blaze of death-defying philosophical swagger, because the old world couldn’t understand that a man like this was the future.

Although everything is heartbreak and shambles now—I think I can finally hear Plato saying (I’m slow)—there is still such a thing as the perfect beauty and perfect wholeness signified by our longing for that in our hearts. And everything, no matter how broken, can participate in this perfect beauty and perfect wholeness, which we know, but cannot see, and can always move closer and closer to the final convergence of seen and unseen beauty—without having to be already perfectly whole, and already perfectly beautiful, right this very moment.

Reality is a gradient, not a binary state. And the top of that integrating gradient is no less real than all the fragmentary stuff near the wretched, life-disintegrating bottom of it, which is where we live our lives for the most part, but is not the only place to which our lives belong.

Of course there are pitfalls to fall into, contemplating the world being another way, as there are also pitfalls inherent in every ambitious act of human creativity. And if historically we’ve lived inside two related but orthogonal metaphors for envisioning alternative worlds—the first “vertical” and Platonic, imagining another world beyond the sky, a “higher” world, whose beauty is like the beauty of the stars and planets—and the second “horizontal” and Hebraic, imagining another world beyond the horizon, a “future” world, whose beauty is like the sunrise of a new day, the “day of the Lord”—then, even if both approaches are rooted in what it feels like to be a human body, with both feet planted on the Earth, either looking forward or looking upward, the “vertical” approach is probably the more disembodying of the two, we can perhaps now agree in retrospect:

He who has got rid, as far as he can, of eyes and ears and, so to speak, of the whole body...who, if not he, is likely to attain to the knowledge of true being? ...What is purification but the separation of the soul from the body?...The soul gathering and collecting herself into herself from all sides out of the body, the dwelling in her own place alone, as in another life...the release of the soul from the chains of the body?...The lovers of knowledge are conscious that the soul was simply fastened and glued to the body—until philosophy received her, she could only view real existence through the bars of a prison...because each pleasure and pain is a sort of nail which nails and rivets the soul to the body...[she is] infected by the body...and has therefore no part in the communion of the divine and pure and simple. (Socrates, in Plato’s Phaedo)

The soul as only “fastened” and “glued” to the body, purification as “releasing” the soul from the “prison” of the body, to which the soul has been “nailed” or “riveted” by sensory input—that withdraws too far into left hemispheric consciousness, to the exclusion of the right, as the neuroscientist Iain McGilchrist would frame it (and here he’s talking about Descartes, though he could just as well be talking about the whole caravan of world-denying spiritual nihilists, from early Plato all the way up to the late modern castaways of the Meaning Crisis, now dreaming online of a desert island apocalypse):

Detached from the body, its tiresome emotions and its intimations of mortality, he aspired to be ‘a spectator rather than an actor in all the comedies’ the world displays. All-seeing, but no longer bodily or affectively engaged with the world, Descartes experiences the world as a representation...[this] enables him to achieve his prized goals of certainty and fixity, but it does so at the expense of content...Affective non-engagement could be said to be the hallmark of schizophrenia. The sense that the world is merely a representation (‘play-acting’) is very common, part of the inability to trust one’s senses, enhanced by the feeling of unreality that non-engagement brings in its wake—nothing is what it seems...in all its major predilections—divorce from the body, detachment from human feeling, the separation of thought from action in the world, concern with clarity and fixity, the triumph of representation over what is present to sensory experience...the philosophy of Descartes belongs to the world as construed by the left hemisphere.

(The Master and His Emissary)

(I recognize a lot of myself in that.) The strength of the vertical orientation towards “higher worlds” is also its weakness: It is basically unrelated to time—it’s imagined to be eternal, changeless, beyond the flux. Consequently, it becomes only loosely related to space, which in embodied reality is inseparable from time, and thus both one’s own body and the Earth come to seem even more unreal here and now, solving the problem of the world disintegrating by disintegrating oneself even faster.

The Hebraic imagination stays more rooted in the Earth, more rooted in the human body: There is a new world dawning on the horizon—the “day of the Lord,” the “Messianic age”—and it is dawning on Earth, this Earth, as we can touch it here and now with our hands and feet, even if “no eye has seen, no ear has heard, no heart has imagined” how deep and wide the watercourses of divine transformation from on high will flow:

The wilderness and dry land will be glad.

The desert will rejoice and blossom like a lily.

It will blossom profusely,

will rejoice with joy and singing,

will be given the glory of Lebanon,

the splendor of Carmel and Sharon…

(Is. 35:1-2)

Nevertheless, there are cultural states of such catastrophic unreality, that you feel you can’t look toward the horizon anymore, toward Earth and time, that all there is left is to look up:

Down in the street little eddies of wind were whirling dust and torn paper into spirals, and though the sun was shining and the sky a harsh blue, there seemed to be no colour in anything, except the posters that were plastered everywhere...He felt as though he were wandering in the forests of the sea bottom, lost in a monstrous world where he himself was the monster. He was alone. The past was dead, the future was unimaginable…

—a paragraph from George Orwell’s 1984, of course, which, apart from being the most deadly accurate of all science fiction dystopias, is perhaps also the most apt description of what it feels like to stand in the utopian strip malls of the American desert of the real. And perhaps also something of what it felt like to stand in the ruins of the Peloponnesian war.

And so there is, and must be, an ever-moving harmony of vertical and horizontal orientations, which will always be somewhat beautifully, somewhat disastrously unattained and unattainable in any one time and place, because of the lag between what has already happened in the world we share with everyone else, and our grasp of the implications of what’s happened for our possible but imperfectly imagined worlds.

In this writing series and in my writing in general, beginning with Sunlilies: Eastern Orthodoxy as a Radical Counterculture*—which is exactly what

said it was, “Wild, hopeful Christian dreaming for dark times”—I have been imperfectly reaching toward something which doesn’t already have to exist perfectly here and now, though I’ve wanted it to, and told myself that I needed it to. But by the same (Platonic) token, so many things here and now already participate in the future world I’m reaching for: The wind blowing waves through lilac-scented lilac-blossoms, the double-helical pathways of sparrows flowing through the air, the fragrance of lemon-yellow honeysuckle blooming from a chainlink fence, the smell of black tar weeping from a railroad tie in the yellow sun—but even more than these, the band of Orthodox fellow-strugglers in the home parish I’ve wandered away from for awhile, lost inside my inner world.And so, for my sake, as well as for yours, I wish to slide my visions to a more distant but also more familiar future, so there’s still somewhere for this rush of creative world-building energy to go—but in a way that leaves a lot more space to just take or leave whatever’s either treasure or trash, not getting too hung up on either one.

Call it Sabbath Empire: Notes towards an Orthodoxy of the birds and the flowers a thousand years from now. But if you’re not Orthodox (as I think most of you are not) and you have no desire to be, that’s OK, too—you’re still already included in that vision anyway (as of course you are), because Orthodoxy itself is not absolute, but only slowly and painfully making its way up the reality gradient, like everything else is, converging like rays of sunlight on the perfect beauty and perfect wholeness that all of us desire in our own hearts, and which we know in our heart of hearts must be our true home.

Postscript

This past Sunday I went back to church for the first time in months, intending in Dostoyevskian fashion, simply to “love everything” if I could—every leaf, every flower, every icon, every billowing cloud of incense, every sunlike candle, every beelike song, and especially every human person—finally understanding that “everything would be easier” if I just floated along in the “ocean of everything” that the Divine Liturgy is, if “I myself were more pleasant than I am,” asking everything for forgiveness, at least in the silence of my heart.

And yes, I did go out a couple times to watch the sun shining in the maple leaves, the green leaves flickering in the wind, to take breaks, and also I shed tears staying inside, facing the cresting waves of the liturgy, though not at the part I thought I might—the sublimely wounding tenderness of the Georgian Cherubic Hymn—but right after, the simple but joyful continuation of the litany of the faithful: “Lord, have mercy, Lord, have mercy, Lord, have mercy.”

Because it was so good to know that I, and all of these also lovely, also broken people around me, were still absolutely nowhere near completing our prayer to the Lord.

Love always in Messiah,

-graham

* Another American printing of Sunlilies should be available in a couple of weeks or so. I’ll let you know when and how.

Oh, and I forgot!--this is the chanting in the background of the audio: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fRK4jYdmRUk

It's great to read this. I was sad to think that you were leaving us. And I have never seem that Dostoyevsky quote before. That's the meat. This is the heart of the matter.