Working on this psalms started out with a desire to explore the Hebrew root words in one of the psalms envisioning the world coming forth intimately from God, rather than being constructed, as if from afar, inside the space-time container of an everlasting black Void, as the idea of “Creation ex nihilo” can, with consequences, come to be imagined today. (To the amazement of a few, the amusement of some, and possibly the chagrin of many, in last week’s essay I attacked that sacred cow—though I did so hiding in the shadows of Philip Sherrard’s wings, as usual!)

In typical Hebrew parallelism, Psalm 90:2 says God gave birth to the world in two different ways:

Before the mountains were brought forth (yalad),

Before you formed the Earth and the world (hul).

(This is a conventional translation; I’ll give you mine below.)

Yalad, in its various forms, is translated elsewhere in the KJV as to be born, to give birth, to beget, to labour, etc.

Hul—which sounds pretty tame and abstract above as merely “formed”—is translated elsewhere as to twist, to whirl, to dance, to writhe, to be in anguish. So, the mental image is of a woman in the agony of giving birth, moving around simultaneously in ecstasy and pain, as a kind of dancing forth her child into existence.

You’ll see past the paywall how I handle those roots and do my best to make that imagery stand at the forefront—and the rest of the vivid roots, as well; the whole psalm is very, very vivid and alive—and I would like us all to experience it as so.

But as I began to work on the audio version (also below the paywall, after the text), I focused on the agony, pain, and sorrow which runs throughout the psalm—not just God’s agony, in giving us birth, but our agony, in living out our days, like blades of grass under a blaze of sunlight (this is the psalm’s imagery, not mine).

Twenty audio tracks come together for the final soundscape. I won’t describe them all, but just let you try to hear them. A few clues, though: The poem begins and ends with children, the cycle of the ages. The sounds of war are recorded from the conflict in Syria, still ongoing—but it is meant to represent all wars, in all times, which lays the human condition bare, as nothing else does. The children speaking Arabic are refugees of the current Syrian war; the man reciting instructions in English at the end is a teacher in a refugee camp. At a certain point in the poem, a Syrian girl cries out “Abba!” trying to find her father, after a bomb blast (these two were eventually reunited; the story didn’t end like that for many others). The windchimes are the surprising, loving presence of God; the mourning dove singing in harmony with the girl’s pain is also this.

By using these audio clips, I don’t mean to colonize the suffering of others, just to acknowledge it and mourn it. If, when we’re talking about God, we’re not talking about the real world where children suffer, then we’re not talking about anything at all, and should stop.

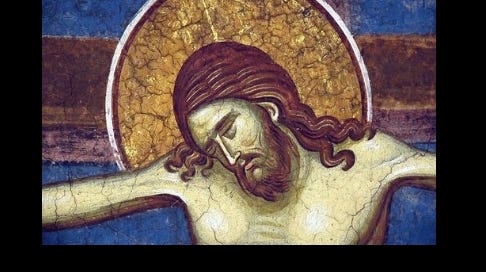

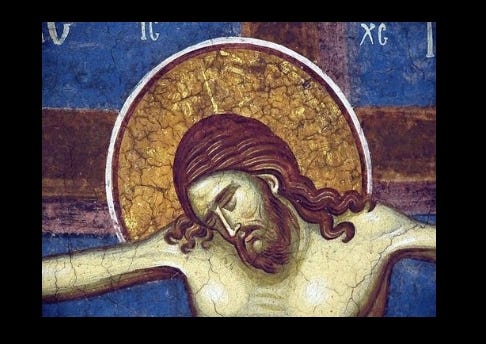

Finally, when looking for a image that would fit the text and the audio, I came across the above—not at all what I was looking for. But I think Katherine Sanders captures in this icon both the agony and the bliss, both the maternal care and the suffering warrior spirit of the One who brought us into existence, and nurtures us for Eternity, through much pain and travail.

Text and audio below, past the wall.

love,

graham