Over Here Where The Trees Are Taking Their Sweet Time Of Eons To Slowly Crash Through The Human Stone

With Andrew of Bog-down and Aster

Graham’s note: This is a collaboration between myself and Andrew of the Substack

As you’ll see below, I love Andrew’s poetry & his way of seeing the world. If you’re so inclined, please do subscribe to his ‘Stack; I would love to see you all over there!“Now, my friend, let us smoke together so that there may be only good between us.”

— Black Elk

Graham ▼

Andrew, you're a madman. Your poetry is so alive, it obviously came from your heart; I wish it had come from mine—it certainly resonates in my own heart. "Rabbi" for example:

You mothered, you mattered

you aurochs that once caught Aaron's eye

now siren to the instars,

now ochre on the wind

blown from the palm

of a world left behind.

I mean, that's killer—sonically, imagistically, everything. But you're also speaking the language of my heart when in the poem you reach out for this Rabbi (Yeshua, it seems) who is of the Earth, and beyond religion—Yeshua, who reaches through your poem to

those who do not need you to have risen

in order to come after you to Jerusalem

where, bathed in all the pigments of unfinished life

feather to feather, skin to skin

and all the petals a sea upon which

we will learn how to die.

I'm an Orthodox Christian; in my heart of hearts, I know the resurrection happened. But I also wish the evangelists hadn't retrojected the resurrection back into everything they wrote (as of course they would have)—not because the resurrection didn't shed light on so much that they had missed before as hamfisted proto-revolutionaries, but because then we never get to experience what it was like to have encountered the man before knowing anything about the resurrection to come—this man who, as I tried but failed to say in a nonfinished poem of my own, "walked in the sunshine of a quiet apocalypse up to his waist in white lilies." I'd like to think I would have loved him, had I been there, with or without any sky-walking powers, that my beard simply would have bowed before his beard, because it was so godbearing i.e. so human, not zombie.

Andrew ▼

Just returned from following the breadcrumbs through your forest liturgy at the end of times. Enchanting words in the best way, bare-foot down into the Under and fingers brushing the wet green to anchor the soul in the animal of it all.

Yes, the Rabbi in that poem is Yeshua though many orthodoxies short of a full deck here. No easy certainties left to the nature of his going on and where exactly the bones in question were when the finger of the uncertain plumbed the wound in the side. But still knee deep in the wake of his comings and goings.

It is a revisting that I never expected. Some time ago, after a long tangle with monotheism I simply slipped out from Jerusalem at dusk and never imagined I would look back. Some dark years retooling the compass and then I found a North that was a real homecoming in animism. What I lacked in personal history and recent ancestry in that peopled cosmos was made up for in the return to a fellowship with the nonhuman (deerpeople and dark mothers and such) that was an echo from a nearly forgotten childhood. I found myself no longer in need of many of the more well-worn hypotheses and, as I already said, even fewer certainties. Yet, in the clutch of animism and the whirl of a many-armed multiplicity, the Galilean peasant’s grip just quietly held without my notice until recently. And then some turns in woods, a similar reapproach by a trusted guide and the friendship was awake again. A fundamental friendship undeniably, a discipleship arguably but one without bannisters as Arendt would say. Not the first to be held as such of course. "Let us go to Jerusalem and die with him". Not of the order of faith (at first) as much as loyalty to what once brought breath. A once and future...something.

Not that I refuse every constellation of tradition and the puzzling out of all this before our time. Incarnation sticks. Odd for a Jew (Ukranian and Polish yids are my blood) to pick this pocket but it's where my fingers brushed hearth. This god come learning, loving, bleeding seems the only type I could ever break bread with around the fire. When tzimtzum (Luria) withdraws and makes a way for Auschwitz alongside fireflies and baobabs true love would come take the ride unflinching and in full. In a story full of all that has happened I wouldn’t trust a god who never sweated blood and cried out forsaken and alone in that unquestionable authenticity.

I hear you on the sky-powers. Jenkinson points out that belonging means to be beset by longing. The home I seek to re-member doesn't speak heaven. Garden maybe. Redemption surely, but down here among pulse and meristem, salt and tide. I think we are kin there, yes?

(I haven't really strung much prose on all this as a lot of it is still coalescing in my middle. Its bound to be messy. I am in the sea of coming to terms, renaming the things and persons. The high praise of those bits in the Rabbi poem were good to hear. Sorry I didn't mention that. Sometimes kindness like that startles me and I forget to respond.)

Graham ▼

Yes! To belong is to burn with the mild and human and also humanizing anguish of longing—and, also, to enter into belonging in the first place, one must long.

I've always admired people who convert and/or de-convert from and into something—and have never understood how it is that most others seem more or less content with the given. At heart, I'm a nomad and am drawn to nomads—which is not to wander, but to keep circling and circling around the circle of the Earth, in search of what one's ancestors have taught one to long for, what one's own body—the learning of the Earth, on the infinitely-dimensioned clay tablet of the self— teaches one to long for, through the voice of the ancestors.

I converted to Orthodoxy twelve years ago in the sense of going through the catechumenate, undergoing chrismation, et cetera, but I'm still very, very early on in the process of going up the endless rainbow bridge of inner conversion to the infinite self-similar fractal-Orthodoxies of the heart: Rose Orthodoxy, Peach Orthodoxy, Canary Orthodoxy, Grass Orthodoxy, Bird Orthodoxy, Flower Orthodoxy, Orthodoxy of the stratospheric clouds drifting across infinite fields of blue Orthodoxy awakening into the supreme and ineffable non-Orthodoxy of the stars. (I'm making all these up, of course, no one talks like this, and perhaps no one should—there are so many layers that have to be stripped away, and it'll never end.) I think of heliotropic flowers longing for the sun—but they're only able to do that because they're rooted in the Earth; they belong to Earth, so they long for sun. Put them in space, and they neither long nor belong, but just float there as carbon.

I walked away from Jerusalem myself for a long time (a time of longing)—but in my heart of hearts some fire began to tell me that this "god come learning, loving, bleeding," as you say so beautifully, if he's not "God" then he's better than "God" anyway, so forget "God"—this brown-haired Human One is all my heart ever wanted, or ever could want—an inexhaustible Garden.

Is he in "heaven" though? You say your longing for home doesn't speak heaven—mine, neither, if by heaven you mean what I call holographic neverlands in the sky—the nonplace from which shimmering Obi-Wan Kenobi speaks to Skywalker in the form of bad CGI.

If you mean the actual sky, though—the infinite sky (not just the dome of gas molecules we see in our science-distorted, universe-desecrating eye)—I long for that, like a flower longs for that, also; I feel we belong to that, because we belong to Earth, which is almost just sky-longing in the shape of a cacophonous biosphere.

As I shall perhaps say in some other essay:

Sun and rain come from the sky, making all life possible, making all things grow and flourish; the blue expanse, the white clouds, the many-colored rainbows, the silver moon and yellow sun, the stars sparkling along the Milky Way, are all inexhaustibly beautiful, infinitely mysterious, seemingly untouched by the violence and senseless craving that ruin our artificial landscapes down below; trees, flowers, and human bodies are oriented skyward, growing toward the sun—it's as if we can hear the sky calling, as if the fullness of our lives is hidden there; the sky encompasses, surrounds, embraces, and contains everything that ever was or ever will be, but itself is uncontainable, infinitely free --

– But you can breathe the sky; it's in us—and we're in it!

You said "incarnation sticks." And so it does (since Yeshua, I could never believe in any god who doesn't take animal flesh, eat bread and fish, laugh with his friends, and then completely and totally die and still refuse ever to leave the human body)—but the word doesn't necessarily have to stick; some Latinate words are pretty OK to my ear, even nice ("transcend," I like that one, in spite of everything)—this is one I'd rather leave behind, since it makes me think of chile con carne—it makes me think of Mexican food. Perhaps if I thought of carnations, I'd like it better, but I don't. I've been saying "embodiment" a lot, and that's alright—but perhaps you've got a better kenning for it. Or perhaps someone else out there in the world does.

Thanks for the kind words on my "Forest Liturgy" piece, little dandelion puff that it was—what you said above, and also what you said before:

A biome tilted toward the delight of wild donkeys...That is an order I could apprentice into. Lovely longing here, Graham. Even your taste in holy fathers, threadbare and grubby yet starlit, can subvert my normal aversions.

But I wonder—from your side of the beautiful abyss over there, can you look at what I'm shouting from my side of the beautiful abyss over here, and point to anything you can challenge me on? (Or us: The legendary Orthodox monolith; it needn't be personal, but it could be—either way is fine, so long as peaceful). One thing that drew me into conversation with you was your thoughtful challenge of something else—"Let God arise, let his enemies be scattered" which, our memories being what they are, of course sounds like "Let [insert technological empire] arise, let [insert indigenous people] be scattered." I appreciate and long for civil discourse according to the old ways—where two people can disagree on words, but agree on heart—and think that agreement on the words matters, and also the heart.

Andrew ▼

Thanks for all that, Graham. Plenty to recognize. I am grateful for the turn toward challenges. We live in a time that runs to the mirror to bless its own reflection on the hour. A bit of honey and the dissolution of tension are the sacraments of its faith-fill.

But I don’t find that your open hand conducts any bullet points of my dissent. We sleep with the same rock next to our heads. Even if, maybe, we have different ideas about its ability to map us back to the quarry or the wisdom of that desire, we both wake on our way back to the mother’s homeland knowing that the G-d(s) be in in this place.

Yet, I hear you on the right to learn from each other. Only wheels that carry no weight can be held exempt from constant trueing. The honorable mutiny is a lost art among algorithm’s assurance. We used to learn by shapeshifting, now we lust after stasis. Let me see if I can kick us up something to tussle over. In what follows I may very well be telling you what you already knew or rather manufacturing dissent. Let me set aside Sancho Panza for a moment and give Quixote full rein.

There is a great deal of talk lately about rewilding Christianity. Some of that talk seems to have an easy rapport with ideas about a return to tradition, even a nostalgia for what has the scent of some relative of authority. Which may not be an entirely wrong-headed hunger if can avoid the delusion of rewinding the tape and hoping for a different song. I can’t help but wonder if there is some dream here to embrace a short term memory loss as a pass back to all we miss, as if the living cell of the church could break with the organelles of certainty, erasure, and world-hatred that have lived within its walls much too long for any seam between symbiosis and identity to be unstitched without a long deserved death and burial.

I already have seen the glee in what the Faithful read between the lines in what they see as vindicating conversions of deep thinkers like Kingsnorth and bards like Shaw. I have already seen gatherings around the splintered stump of a mast long torn from the ship, the annular rings–centuries of exclusion and inquisition–numbered with nostalgia, the literal and that static once again being sung to as if they were the meristem of God. Not that I see that in Kingsnorth’s writing itself even if I don’t read the deep past of our break with Eden or the looming future with quite the same level of contrast and definition as he does. And Martin’s work definitely has no truck with that mess but something nags from ancestral Yid of me for something missing that should precede any reconciliation with a system previously so implicated and inclined.

Here I want to confess I have a lot to reconsider. The fabric of the shirt my sister-self is knitting in silence from bog-down and aster isn’t done and I remain unreconciled myself. Still parts feather and boy, all air over water and no home yet. When I imagine what might true the circle that would carry a person into belonging I know, though it will stretched out on what was, ear-pressed to the Under and feeding my dead, it must be made the Now. The old tradition and its champions cannot answer the questions of the burning trenches of the last centuries while refusing to see a certain type of god was ashed in them alongside his children. But neither can we make it across without the sparks among those shells. A wilding mentor of mine used to hammer into me, in the accent of Yevteshenko, one cannot leap halfway across the abyss. I believe we must re-story this post-apocalyptic place unsainted and unkinged, everything that once was must pass through that Shakespearean sea-change that Hannah Arendt drew from in her speech on Men in Dark Times. The pearls we dive for, what once were our fathers eyes, will not be brought up by priests or warriors but by scavengers. We are more gatherer than hunter now, knowledge now basketed along with us from the ruins in metaphor, the poetic stripped by that which happened of any ability to ever again support a scaffold, and less useful (thank the God) for that sea-change.

We are not of the order of the Axolotl who can grow the leg severed in the violence and rewind the story to find us again fully limbed. The now of our trueing is pegged-legged, half-lit, in the betweens. I believe Arendt that Benjamin was correct in seeing that the transmissibility of truth was now replaced by citation. The past was built on stone. Today it would be the stitch. Stephen Jenkinson is convincing when he says this unculture of ours inherits, almost without work, its prejudices but no matter the effort, no wisdom at all. I heard Rune Harjo speak about how the Nordic people used to go to the Sami when in need of religion and wisdom. Not to plunder the stories and rites of the Sami but to learn from how they might return home afterwards and gather their own. How does this transfer over to the those like me, here on this plundered soil, mix breed, my only medicine bundle the practice of exile? Next year in Jerusalem. This I yid up from a blood that allows no easy identification with a nation state or some hubris about the West because all the kiddush-songs and shtetl bones from the Rhine to the Black Sea stand between. Not to the mention the present realities of the sons and daughters of Ishmael, without whom Jerusalem simply isn’t. Yet still, despite the world that we are not of, I think the one we do look for is of the same altitude. The twelve wild geese and their sister do not come human and home to the kingdom where they lost themselves but they do come home to black earth.

Coming back to orthodoxies I was thinking here about the poet Paul Celan's recoil from rhyme and form, his unbinding of syntax and the mad stitchery of compound words and his need to stitch the ruins together, almost theriomorphic in its stranging of the familiar. All because his mother tongue, German, after its handling by the Reich had to "go through its own lack of answers, through terrifying silence, through the thousand darknesses of murderous speech." And rightly so.

How much more would be demanded from any orthodoxy that would be wilded? Theology is the temptation to fabricate the unwavering claim from once whispered stories, to make a searchlight from blue ember of our dusk, to found a fortress from the nurturing dark of womb. I suspect nothing wild can survive in a biome friendly to such processes. I am interested in a liturgy that doesn’t just compliment such a movement but rather refuses it almost completely. I find this type of refusal in the midrash of the Zohar and other kabbalistic texts.

I do not believe we can rewild Christianity. It was never wild to begin with. It begs for system, for canon, for the in and therefore, the out. It is the hardening-after, the irresistible need to close the circle. Theology seems to me to be a place that story goes to have natality tooled into repetition and ambiguity pinned through the wings to the page. But I suspect maybe you have another way of seeing some of this and would be glad to hear you windmill my giant. What could be better that to actually find out there some gentle wind-driven way to again make bread. Should it prove a village where Yeshua of my ancestry and the triple goddess that came before Moriah might be a both/and rather than an either/or, that would be even more interesting.

More later on deer people and incarnations or anything else that interests. Didn't want to swamp the raft.

Graham ▼

...And then, may I note, like only twelve hours later, you dropped this flowerlike hydrogen bomb of a poem on your Substack, called Colony Collapse Disorder:

...The sun is going down, beautiful winged sister,

but this night you will not look to the hive;

this night, spread out in an isolation

conducted by fate, nectar and the wind,

you and yours will leave a testament in the wet grass..

On the wind I hear a queen

counting down the names of your kin

Only the tip toe of evening,

already in the dark between the trees, answers.

I will sit with you for a while.

Tell me of empty combs.

I will tell you of empty words...

How beautiful!

Well—can we, or can we not, rewild Christianity?

In a sense I suspect anything with “re” as a prefix, since to me, this also sounds like “rewinding the tape and hoping to hear a different song,” as you say. In particular nowadays I feel at odds with the glee for “reenchantment” as it sounds like if we only just [fill in the blank], then Tinker Bell will arc overtop the castle of the universe once more, and the universe will glisten with fairy dust once again.

I also doubt that “we” can just “do” things to vast forest-like systems of thought and feeling that we ourselves are deeply intertwined with, and are—like “Christianity,” like “civilization,” like “the West,” like “humanity”—there's just nowhere where we could climb to gain the perspective, and the power, to understand what these things really are, much less to re-this and re-that them.

But is Christianity rewilding itself? Is the Earth rewilding Christianity?

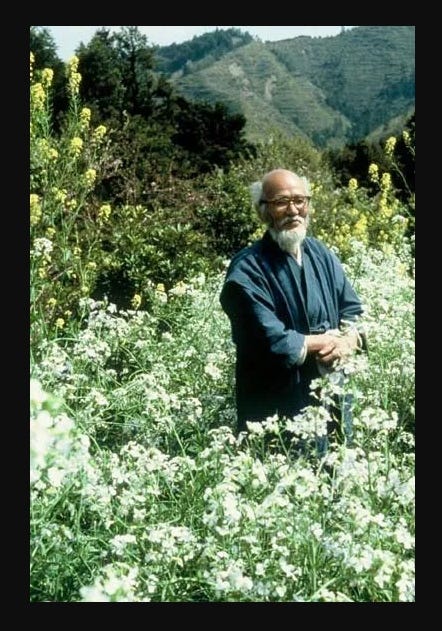

Here, I think metaphorically of a certain lithic beauty that becomes possible only after you build something meant to last forever, but it lies, apparently in ruins, as the forest enfolds it again—the Angkor Wat temples in Cambodia, for example:

Are Buddhists rewilding Buddhism here? Is Buddhism rewilding Buddhism? Is the forest doing it? Is it God?

Or is the temple actually becoming more truly itself, as it matures, and therefore it's starting to seem much more like a tree than it once did?

The Paul Kingsnorths and the Martin Shaws of the world are over on this side of the Christian monolith, where the trees are happening.

I can only speak for this side—and I can only speak a little, having experienced only a little—but when I talk about “Christianity” it's almost all tree, and almost no stone. The desert fathers and mothers of the old days—not to speak for them, either, but I think they would have recognized themselves over here where the trees are taking their sweet time of eons to slowly crash through the human stone. After all, they were the ones who ran away from priests and churches, so they could pray among the ravens and the jackals.

I don't at all relate to other sides of the infinite monolith of Christian thought that are still, or are still trying to be, pristine: everything under control, total certainty established, citations from the past always at hand, always ready to drive away the living green stone-crushing mystery of existence.

And to be honest, we in Eastern Orthodoxy—we can fall into that kind of life-denying theological ossification, too, as anybody can—but we see those issues as much more native to the West—the West which derided our hesychastic monks in the forests of Athos as only so many “navel gazers,” supposedly deluded in believing they could touch the mystery of God directly in their own hearts by making their own bodies into a circle, breathing themselves into an ecstasy of Jesus Prayer. No, no, said the anti-hesychasts—God is up there; we're down here—don't get those two things confused!

And the whole scientific enterprise of the West flows from that separation of the sky of theology from the waters of the human mess—and so does the rigid and lifeless perfection of systematic theology: God is up there, and cannot be accessed; he has, however, downloaded to us as much information as we need in the form of a book—let's just organize what's there, adding nothing new—certainly not from our own personal feeling and experience!

But in Eastern Orthodoxy, mystery is the center, not the periphery. Words are there to remove obstructions, and ultimately must fall away. There is no such thing as systematic theology in Orthodoxy, except for maybe systematically dismantling all possible notions of God that anyone wants to hold onto instead of reaching for God directly in the heart. As Dionysius the Areopagite said of the divine:

It can neither be expressed nor conceived, that it has neither number nor order...that it neither lives nor is life...that it is neither science nor truth, nor sovereignty nor wisdom, nor singularity, nor unity, nor divinity, nor goodness; neither spirit nor sonship nor fatherhood in any sense that we can understand them; that it is not accessible to our knowledge or to the knowledge of any being; it has nothing to do with non-being, but no more has it anything to do with being...that it eludes all reasoning, all nomenclature, all knowing; that it is neither darkness nor light, neither error nor truth; that absolutely nothing can be asserted of it and absolutely nothing denied...

But about this rewilding: Look, I'm just a leaf on the tree myself, Andrew; I can't look down and tell you what the whole tree means, when I myself am just trying to live and grow and thrive in the sunshine and wind afforded by my place within its holy vastness.

But it seems like the pattern of rewilding has always been there: Look at Moses, for example—the new Sargon of the dirtbag kingdom of God growing like weeds right in the middle of the kingdom of Egypt—Moses, who talked to I AM as a tree of iridescent flames, having re-grown his beard and tended sheep for forty years, a fugitive of Egyptian justice after bashing a dude in the dead; Moses, who had been a clean-shaven, power-wielding highly civilized Egyptian prince—you could say he himself was made wild again during those forty quiet years of pastoral life, to the point that he could hear the voice of God in a tree, and that he went back and led anyone who was up for it—not most Israelites, but a few, anyway—away from the limestone gleam of the Egyptian complex, and back out into the wilds of the desert.

And look at Abraham, the great ancestor to whom Moses was trying to return his band of Sea of Reeds-crossing, roving Burning Man festival of forty years: Abraham, called away from Ur, the shining metropolis of its day.

And look at Jacob, renamed Israel only after he slept on a stone for a pillow and wrestled with the divine-human twilight.

And then also dreadlocked John the honey-tongued locust-eater, leading, pied piper-style, a New Israel away from the city, from the pathological rigidity of religion, out into the desert.

Yeshua, of course, joined him—he went into the symbolic drowning and rebirth in the Jordan that John held out as a gateway into the New Israel, a renewed desert Judaism. And Yeshua's was a wilderness Judaism to the hilt—always on the fringe, on the outskirts, multiplying bread and fish in the sunset realms of grass and stones and the dirt-poor outcasts of the system. So how very fitting that when the gospel writer John wants to characterize Yeshua's way of life and mission, he shows Yeshua coasting into the temple, then kicking over a bunch of tables and doing a reverse Noah's ark with the sheep and doves and oxen, et cetera, who had been imprisoned there by human, all too human religious ideas!

And then you have his earliest followers, whom I've already praised in the words of the critic of Christianity, who said (as if this was supposed to be an insult!)

They cannot tolerate temples, altars, or images. In this they are like the Scythians, the nomadic tribes of Libya, the Seres who worship no god, and some other of the most barbarous and impious nations in the world.

But that's high praise for us!

So, to my mind, this cycle of a return to the wild has always been there.

And thus, as the stone temple of Christianity crumbles beneath the trees growing on top of it, it is actually becoming more truly itself.

I look at the picture above and say: That's not a tree reconquering the space that the temple had taken long ago—that's a tree-temple, partially built of stone, partially not, that's finally flourishing as it was meant to.

Or, that's how I'm working on seeing things, anyway.

Andrew ▼

Dear Graham,

Let me simply bless this pattern you raise as a signal fire from your peak, Angkor Wat. Salut the order of symbiosis, the glory of flotsamed sanctuaries incarnated by the holdfast of desire and the preeminence of the tree.

I think you are right to suggest we don’t really have to have that much to say for a Christianity of the scaffold beyond raising a glass together to the many nail-pierced feet that would dance under the moon or around the sunpole on its grave. Benjamin spoke in his Thesis on History of the weak messianic power we as the present inhabit and the resulting claim upon us from the unredeemed past. The only happiness that can deserve envy he said is bound up with the air we could have breathed or the bed we could have shared. There, where the ancestral resistance embers and the wonder still waiting unfulfilled watches our next move, is where any blueprint for tomorrow must get its ink. This substitution of our feet for the weight of those missing upon the grave of Christendom and all the other scaffold grounds is a debt we owe our dead, human and non, but maybe the Siddur of the Ruins doesn’t need to praise the Devil with our attention the barbarisms on every page.

One last time let me say I don’t trust Christianity with a big C anymore than I once did the Revolution with a big R. Like Camus I would defend my neighbor before either of them but I can drink to this Angkor Wat-ing of our homeland. Thanks for that.

I think you ask me about tradition, authority, and dreams. Let me start in the middle. Who do I set aside my own opinions for? Who are my masters? I am sure I have masters. I am sure the most problematic are the ones I don’t see or maybe the ones I serve despite the opposition they express to the dreams I pretend toward. Setting aside the Yeshua question for a moment, because he really is something else, I would say that I see the boundaries of my imagination are like a circle salted on the earth and set about with amulets hung by ribbons from the branches around the border. These amulets are an oddly specific collection of bits that I hold as trueing to my wheel, shorthand markings for larger discussions in each of their musical keys. There is a Jewish story of the Lamed Vav, The Thirty Six Just Ones that secretly uphold the world with their being. I would like to imagine them as my authority. More calls to a way of being than ordained rulers of the mind per se. The hips of the whale might be another amulet. Mutability and the call to the Sea but always the vestige of lost garden and the hoof in the wet earth. I have a friend who has done a great deal of work in the spirit of his mentor Gimbutas on decoding the language of the paleolithic, the many geometric signs that we find on the cave walls and handheld art from the dawn of the human mind. He believes these symbols tend toward processes or ways of being in the world. There is a hint there of the original participation that Barfield speaks of. That lost immersion in the cosmos is another authority whose terms I try to remember.

Mandelstam said a razinochinets has no need of a biography, just a list of what he has read his story is done. The syllabus of this recent crossing back over has been short. Martin Shaw’s work Scatterlings to Parzival to Moriarty has been the map in my pocket. I say reading but plenty was just hearing. His telling aloud of Bardskull is simply upending and, I think, almost alone in its ability to fetch you into someone else’s under and still ring in the key of your own home. And strangely I listen to his podcast with the writer Keenan almost once a month, especially when I feel a bit shadowed. It is another of those strange amulets for me. It is tempting to let this be the start of a list of sorts but I think I will leave the library out for now except to say I don’t pretend to be an original thinker. We all stand on the shoulders of giants but I more than some find my own ideas are a collage of the things I collect among the stacks and I have plenty of delusions but not the one where I imagine I am anything more than a parrot with good taste. More and more these days the ones for whom I exchange my views for theirs are the old stories. Fox Woman Dreaming, The Twelve Wild Geese, and a tale Rabbi Nachman told called the Lost Princess come to mind off the cuff. To my relief after proof reading my own phallic star chart above , I find all three tales all center the feminine. This seems honest. The dark between my trees has a necklace of roses and skulls hung round its jugular.

How do you approach the scarcity of the feminine on the surface of the Sea we both seem to sail, Graham?

I will leave this here Graham. Rough and unedited just to not delay a response any longer. I am about to be outside of internet access and wanna try to get a post up on Bog-down. Hopefully it gives you something as a canvas for you to lead us on.

(….)

(and then later)

I returned tonight to your essay Blossoming on Earth Like Flowers. It seems to be exactly the sort of translation work we need to be able to see what the grief of our individuation has hidden, to begin to pretend toward some sense of the final participation that Barfield is on about. The un-animism that is behind so much of the damage we do is based in our insensitivity and I think you muster our coming to our senses here. Senses that, in those tells from the once dead (NDE), seem as animal as ever. This is not the age or the order we find to be home but yet this earth is where we belong. The where we are beset by longing for. I reread Lewis’s Weight of Glory sermon working on an animist critique of some parts of it. I will send it along at some point. I think he betrays his own longings when he identifies this “world” that is not our home with the wind/water/earth we are so clearly one with. The kingdom of heaven is in your midst. The lack of all the peoples, humus to hawthorn, in some of our so-called sacred languaging is more an artifact of our poverty of sense, a stuntedness to our dream rather than any trustworthy audit of the biome of the Not Yet.

I wonder if you might say more about your idea of our place among the non-human peoples. Do you see us as a custodial species? What is/are the gift(s) we should be bringing that are specifically human? Some would say the best we can do for the Wild is to stay the hell out of it. Others sense a brokenness that may precede our touch, and with it, a need for a once and future tending we have yet to reapproach the skill set for. I suspect any path to such skills will demand a long, silent apprenticeship knitting and listening to the non-human voices we have long ignored. What do you think?

Graham ▼

Andrew, you've read a lot, brother. I've read just a little, but I have, like you, felt a lot.

The scarcity of the feminine, our place among the non-human peoples, our specifically human gifts—to my ear, Yah's holy breath is the music that sings of all three together, and in the same place, the garden: “Then Adonai Elohim took the man and gave him rest in the Garden of Eden in order to cultivate and watch over it” (Gen. 2:15)

In this prophetic vision we are not, on the one hand, feral apes, lost among the oceanic green—nor are we, on the other, forest-slashing cybernetic gods, replacing the green with well-behaved chrome. We are, or are meant to be, fundamentally gardeners: Those who are quiet, who watch and listen carefully, who observe the cycles of energy and nutrient flow in the world that Yah made, and step in slowly, wisely, to make our mark, to co-create a world in which humans, plants, and animals, sky, wind, and Yah, are all at home together.

The non-human peoples do a bit of gardening in their way—leafcutter ants, for example, transporting leaves underground, establishing a perfect climate for their preferred fungi to grow, and not the others—a kind of collective brilliance on their part, but not the result of an expansive vision of what has been, what might be, for all creatures.

We are—or should have been, anyway, and might still be—the gentle kings and queens of nature, who rule without ruling from a fountain of Sabbath rest in the heart, like this:

John's gospel has a beautiful way of telling the resurrection story, which is that Miriam of Magdala stands crying outside the stone tomb—which sits within a garden—because his body is gone (and of course, she doesn't think he's come back to life; she's not stupid—she thinks his body's been stolen, and she had wished to anoint it, as was only proper).

And when Miriam bends down to look into the tomb again, Yeshua says to her, “Woman, why are you weeping? Who are you looking for?”—as a dear old friend, older brother, compassionate rabbi, fiery prophet, Messiah, son of Yah, he's kind of making fun of her—“Is there someone in there, Miriam? Are you sad or something? Are we missing somebody? Should we be crying now?”

And the text says, when she turned around, she didn't recognize him—she just thought he was the gardener (Jn 20:15).

But that's John making fun of us, because of course Yeshua is the gardener!—the True Adam, having died to self, poured out his life for the life of all, become truly alive as a human, a fountain—the Fountain—of life-sustaining harmony in the world.

Eastern Orthodoxy—among all the Christianities of the sunset of the West, it seems—understands that “making the world a better place” is a delusion, until you follow Yeshua down the narrow road in the darkness of the heart, one's own black abyss, inner death, out of which flows one's own many contributions to planetary chaos and death: You have to go down into the tomb, if you're ever going to come out in the garden, as a true gardener, and not just another a garden-destroyer.

But I suspect there are many in Eastern Orthodoxy who imagine all this garden talk is “just” metaphor—as if Creation itself, and the meaning of Creation, are two separate things! And so you should not imagine me—ever—as speaking for Eastern Orthodoxy, but only as speaking to the trees, finding companionship in them, and in tree-people, kindred spirits, such as you, in the wild edges of the garden, where the stones have cracked open enough to allow such tiny little poems as these to exist.

Andrew ▼

I am glad we part from this roughshod singsong for now to the tune of Miriam and the garden. The chant of compañera and cultivation transposed into a minor key that fully owns the hunger in our middle as we rummage the ruins, heart dreaming into the missing feminine and the deep green we were driven from by our own madnesses. What would I need to add to that?

I’m thinking you might like “A Canticle to Holy, Blessed Solipsism” at https://cjshayward.com/solipsism/.

Thank you so much for sharing that conversation! I'd love to settle beside a fire and listen to you guys chat. Of course, I'd want to ask questions and speak so I could be corrected. I believe we could all be brothers.