ESSAY #3: Blossoming On Earth Like Flowers Instead of Leaving It

Rooted transcendence, not holographic neverlands in the sky

All I want of you, men and women

all I want of you

is that you shall achieve your beauty

as the flowers do

— D.H. Lawrence

In The Idea of a Forest Liturgy at the End of Time, I talked about slowly and steadily working to unfold an Orthodox temple in the woods—moving a boulder here, moving a boulder there, planting lupine flowers, building an altar table of logs and old cherry boards—unfolding it like a flower, trying as best I can to cooperate with what God has already created in this space—white aspen trees, blue sky, green moss—with what God is still creating in this space: He doesn't hand Earth over to us as an artifact or a monument, but embodies himself within it as a green waterfall—a living process.

We can participate in that living process in a sensible way or not. We can either go the way it's going, too, towards its culmination in God, or we can hijack it, try to wrest it into our own human counter-world and its metallic sprawl, the world in which our only gods are ourselves and our machines.

That probably sounds a bit melodramatically black-vs-white, us-vs-them—but it's too late now to be neutral on the question of what nature is, and what it's for, isn't it?

Not that neutrality was ever really possible in the first place: As “animals who have received the vocation to become God” (Saint Basil of Caesarea), everything we do is consequential—everything charged with eternal meaning—whether for good or for ill. If we feel like we're on the sidelines, watching it all happen as basically nice people—taking no great, creative moral risks, but also taking no great moral wounds, either—above the fray—this is possibly just an illusion, and we might wonder whether we're just letting ourselves be used by those taking themselves as animals becoming gods more seriously than we are.

Well, I'm no hero myself, usually just lost in the world of my poetic imagination, but what I think about as I work on my forest temple, what I dream about when we sing the Divine Liturgy in it, is the culmination of history that, God willing, it's already beginning to participate in now. As I put it in the last essay:

In Isaiah's vision of the Last Day—the end of history, the end of war and oppression, when the fiery, life-giving presence of God rushes back in its fullness to heal Earth and all her inhabitants of their wounds forever—one of the signs of its coming will be that the places we've made into dry wastelands will become gardens, and our gardens will become as vast as forests....Palaces, citadels, watchtowers, the frenetic rush of the city—all that will crumble, becoming grass and ruins, green pasture for the milk-white sheep of the future. The holy breath-wind of God will cascade down from the sky, a cool breeze, a new life. The desert will turn green and fragrant, gardens and orchards will become as vast and thick and wild as forests, full of life. Both the true wildernesses, overseen by God alone, and also the forest-like gardens cultivated by men and women, will be characterized by righteousness (right-relationship) and justice (harmony with God's way of life, as expressed by Torah). The result of this will be shalom—quietness, peace, serenity, confidence, and Sabbath rest. And then everything we say, everything we do, will be liturgical—said and done harmoniously together, as a way of praising the Father of all things.

And sometimes in reaction to such earthy, biophilic dreaming, I hear an inner voice that goes something like: “But, man, you're a Christian!—an Eastern Orthodox Christian—that crazy otherworldly kind! The ancient Hebrews like Isaiah didn't even believe in an afterlife or an immortal soul; for them, Earth was all they had, all they could imagine—so, of course, for them, Earth's deserts becoming lush, forest-like gardens—that's as good as it gets! But for Christians, especially Orthodox Christians, the kingdom of God is “not of this world”—totally transcendent, totally beyond anything having to do with this lowercase earth of ours, which is only so much dust! Trees are beautiful and everything, but just look at them, man: Stacks of carbon destined to evaporate! And this precious human body you keep talking about? A rotting meat-tube: Death in one end, death out the other!—the immortal soul is where it's at—just let that barefoot bearded hippie-body go, brother, we're gonna migrate to a kingdom beyond the stars!”

And there is some truth to that voice. But in a time when the ascendant religion of transhumanism—which dreams of us uploading our minds into the Cloud, becoming death-exempt, virtual reality gods—has become the dominant ideology of technocrats busy destroying our planet; in a time when this dream of bodiless, genderless, natureless, and therefore also loveless digital immortality—apparently paradise for some—seems to lie behind, or at least go in the same direction as, the nightmare of trans revolutionaries divorcing children from their own bodies—obviously creating hell for a lot of them; in times like these, I want to be careful about distinguishing the Machine’s vision of transcendence—which means abandoning Earth as we know it, from our own vision of transcendence, which definitely doesn't.

Our beloved Earth—blue skies, green grasses, gray snowcapped mountains, sparkling oceans, white clouds, and actual human people who love being humans—for us, these things are eternal, thank God. We love them forever.

And so what I'd like to do for this essay is take the one most Earth-denying passage I've come across so far in Orthodoxy—a shining gem of ethereal overkill, it seems at first glance—and show how, within our conceptual universe over here in the wilds of the Christian East, it's actually just another way of saying how much we love the Earth—the true Earth.

And once we’ve done that, we’ll be able to talk about transcendence in future essays without people thinking that we’re talking about becoming cyborgs or avatars floating off into the digital Cloud, or that we’d ever want to.

So here’s the passage, from Saint Simeon the New Theologian:

Thus also the whole creation, after it shall burn up in the Divine fire, is to be changed, that there may be fulfilled also the prophecy of David who says that the righteous shall inherit the earth (Ps 36:29)—of course, not the sensuous earth. For how is it possible that those who have become spiritual will inherit a sensuous earth? No, they will inherit a spiritual and immaterial earth, so as to have on it a dwelling worthy of their glory after they shall be vouchsafed to receive bodies that are bodiless and above every sense...

Saint Simeon the New Theologian, The First-Created Man

An Earth beyond all sense-perception? An Earth no longer made of matter? Bodies that are somehow bodiless? We can be forgiven if, in the twilight of the Machine, this sounds stupid, like the metaverse—like replacing the solidity of black soil and earthworms and rain-soaked oak leaves and sunlit chamomile flowers and green moss with some hallucinatory Minecraft in the sky.

Well, it's not quite like that in Orthodoxy, though at times in my life it has seemed so. And what I'd like to do first to explain this is to reflect a little bit on what Orthodoxy does to the human body—our connection to the Earth, and to the rest of the cosmos—this human body which, in our spiritual tradition, we recognize that God himself wanted to have, and still has: The body of our brown-haired, brown-eyed, tangle-beard beautiful Messiah.

The human body, among many other things, is a cybernetic instrument, like a thermostat—it's both a reality-gauge, and a reality-shaper: The more attuned to Creation it is, the more our body—especially our face—radiates solidity and inner freedom, inner life—which reciprocally helps all the living beings around us thrive as they ought to, which then helps us flourish as human beings, and so on and so forth—an upward spiral (see the forest icon of Saint Tikhon and the deer at the top of the essay for an image of this happening).

Conversely, the more inharmonious we are with Creation in our bodies, then the more agitated, the more reactive and dimly hunched over within ourselves in a perpetual screentime of the mind we become, the more the beauty of human life within us is replaced by a vacant stare, by inner paralysis and the endless repetition of the inane. This then magnifies the chaos in our surroundings which makes us so sick in the first place—a downward spiral.

Some people are very, very present in their bodies; they radiate peace and childlike joy, and what they say comes directly from the heart.

I have encountered a couple people like this—the abbess of a Romanian Orthodox monastery a day's drive away, for one: It's impossible to tell how old she is, because inner fire just pours from her eyes, her face, her smile—a child of eternity, to use a cliché but descriptive phrase, whose body is coming alive, the more it dies.

When I was at her monastery years ago helping with yardwork and so on, she was trying to explain to a group of us how she wanted us to work together to relocate some boulders in one of her favorite gardens—three or four of us pretty strong dudes, using crowbars. And I guess we were just standing there like knuckleheads, not really grasping her instructions, so she yelled at us, in the mock irritation of an Old World mother who adores her stupid adult sons, “Like this! Like this!” and moved one of the boulders herself, to show us. Like it was nothing—she just laughed.

And were like: Oh—like that—OK, yeah, got it.

And so we moved the rest of the boulders, working two or three of us together on each one, with crowbars and brute force.

And then weeks later, long gone from the monastery, it dawned on me that a dear little old lady moving boulders gracefully and quickly solo, of the kind that took several of us young lads working awkwardly together to move only slowly—something about that math doesn't check out. But in the moment itself, her inner freedom—her life as a true human person, not a zombie lost in the Machine—really was like an immaterial fire shining from the joy in her face; in that moment, her superhuman strength—or, rather, her strength which was, finally, very very human—felt as natural as air and water; we didn't question it.

Besides, we just wanted to hurry up and prove we weren't a bunch of weaklings ourselves!

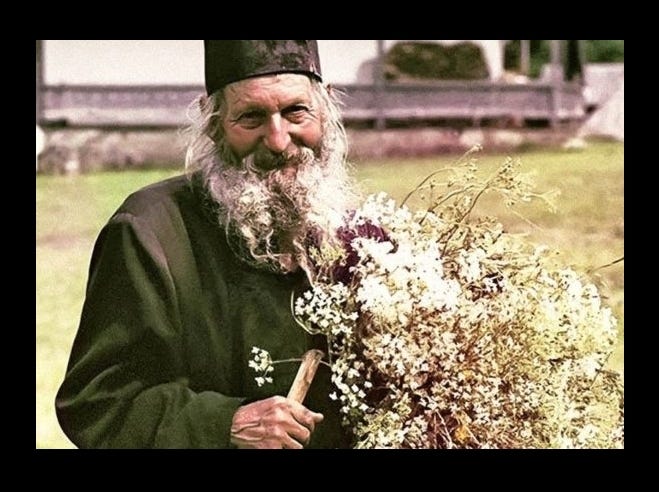

Of course, you have to be there yourself to really feel their fire-like presence—and I hope you’ve met people like this, too—but I remember the inner fire in the face of the abbess, even just by glancing at photographs of men like these:

These are definitely very earthy, very human men, not at all like the brilliant but lost utopian wonderkids weaving the future from their superintelligent machines. No, these are grown-up men whose very beards are almost their own rainforest animals—beards radiating very masculine, earthy, and human life.

And these are precisely the kind of men who totally love Orthodoxy's “otherworldly” poetry, and who trust “otherworldly” men like Saint Simeon the New Theologian with all their hearts. They're definitely not playing around with stupid idealizations—just look at them: Otherworldly, yes, but precisely in being more human, not less, more in tune with the Earth through their bodies, not running away from it—not zombies at all, but people who are really, really, really beautifully there.

And so in this essay, I make a prostration on the Earth before these men, and before my abbess friend in her garden, and I especially make a prostration on the Earth before one of their great spiritual masters, Saint Simeon the New Theologian—misunderstood and persecuted in his own time because he trusted his own direct, personal experience of the Divine, over the abstract theology of his naysayers—and continue the work of transposing his words into mine, as a way to try to listen.

I want to appreciate that there's a certain modified Platonism forming the backdrop of Saint Simeon's words, which he assumes for himself and his audience of a thousand years ago. The Orthodox cosmos is not some ever-shifting “surface” of atoms, empty of humane content, onto which we, the lost orphans of the void, are left to project our own meaning before eating dust; rather, it's the embodiment of a nested hierarchy of worlds in which good things, true things, and beautiful things, are increasingly the same things, all ultimately finding rest in God, the Wellspring from whom they flow.

As the Orthodox poet-philosopher, Philip Sherrard, puts it in his Rape of Man and Nature:

Every sensible form represents both an unfolding and a greater degree of condensation or materialization of its archetype; or, to put this the other way round, the archetype contains and embraces the sensible form in its intelligible or spiritual state....The sensible image does not simply reflect the archetype on an inferior level: it actually participates in the transcendent reality of the archetype. [There is] a real kinship or affinity between them. In some sense, the image is the archetype in another mode, and only differs from the archetype because the conditions in which it is manifested impose on it a different form. Essentially, therefore, the principle is one of transformation of inner into outer, of an interlocking scale of modalities in which the same basic theme is repeated. The Platonic universe is really a hierarchy of Images, all co-existing, each issuing from and sharing in the one above it, from the highest supra-essential realities down to those of the visible world. It is this structure of participation which constitutes the great golden chain of being, that unbroken connection between the highest and the lowest heaven and Earth. In this structure there is nothing that is not animate, nothing that is mere dead matter. All is endowed with being, all—even the least particle—belongs to a living transmuting whole. Each thing is the revelation of the indwelling creative spirit.

I see this as a radiant, treelike structure rippling down from the One who is both the root and the destiny of all things, archetypes embodying themselves “below” as images, and, reciprocally, images finding their meaning and coherence in their archetypes “above.”

Take the sun, for example: Within this Platonic vision, we could talk about the sun having many bodies—or, rather, that there are many worlds of experience in which the sun's one body is expressed, according to local circumstances.

For example, we experience the sun as a blinding disc in the domelike sky, and also as a mysterious power rising every morning causing birds to sing, flowers to open, and men and women to go to work. That is to say, it is beyond us—not just spatially above us, but of a mind-surpassing power, beauty, and mystery. At the same time, though, we can experience it directly as a golden warmth and light on our foreheads, suddenly, when we leave a dark room. We speak of ourselves as going out “in” the sun, of being “in” the sun—and we are; the light and warmth we feel are embodiments of the sun at our human scale—they are the sun, but at the dappled level of reality inhabited by ourselves.

The sun is also manifested in the light-catching structure of trees and other plants, which only grow as they do, because the sun shines as it does. Plants, too, are a “body” of the sun, in that their colors and their geometries, their light-seeking behaviors and so on, bring forth the sun's otherwise hidden dimensions.

And then there is the archetypal sun itself, which, inconceivably, just is what it is, and from which all these particular manifestations or embodiments of the sun radiate, without being exhausted by any of them.

Of course, this is not the only way of talking about a universe which transcends human thought, human language, and always will—but to adopt such a Platonic way of thinking and speaking has historically been our method, in Orthodoxy, to express our understanding that the universe, as Sherrard says,

is regarded not as something upon which God acts from without, but as something through which God expresses Himself from within. Nature...is perceived as the self-expression of the divine, and the divine as totally present within it...If God is not present in a grain of sand then He is not present in heaven either.

Every sparkling grain of sand, every blade of green grass, every yellow sun in the infinite, shining blue sky is an embodiment of the inexhaustible Source of all that exists—and, in Eastern Orthodoxy per se, not just philosophical Platonism, of his nature as a vast communion of love: “God is love. Now whoever abides in love abides in God, and God abides in him” (1 Jn. 4:16). Thus, when Yeshua says

Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven—he causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and unrighteous (Mt 5:44-45)

he is not only telling us who we are—children of the Father—but also what the sun and rain are: manifestations of the Father's spacious, ever-flowing love for all the fallen children of Earth, no matter how wretched.

Within this modified Platonism, “material” and “spiritual” are key words that do specific things. They are relative terms, like “high” and “low,” ways of describing something's position within the golden chain of being.

“Spiritual” does not mean basically holographic, lacking solidity—nor does “material” mean it's just atoms and void, lacking content. Rather, to call something “material” means it's lower down in the hierarchy—more image-like, more diverse, scattered, and chaotic—like fallen leaves; and to call something “spiritual” means it's higher up—more archetypal, more coherent and whole—like the sun.

And making the dust-like things of Earth become so is indeed the work of the Holy Spirit, hence “spiritual” in that sense, too: “They perish, and return to their dust / You send forth your Breath—they are created, and you renew the face of the Earth” Ps. 104:29-30.

As a biblical illustration of the word “spiritual” used along these lines—not as lacking solidity, like a hologram, but as carried by the Spirit nearer the Fountainhead of all, thus emanating more transcendent wholeness, like the sun—here's a passage from Saint Paul of Tarsus:

What you sow does not come to life unless it dies. As for what you sow—you are not sowing the body that will be, but a bare seed, maybe of wheat or something else. But God gives it a body just as he planned, and to each of the seeds a body of its own. All flesh is not the same flesh, but there is one flesh of humans, another flesh of animals, another of birds, and another of fish. There are also heavenly bodies and earthly bodies, but the glory of the heavenly is one thing while the earthly is another. There is one glory of the sun, another glory of the moon, and another glory of the stars; for one star differs from another star in glory. So also is the resurrection of the dead: Sown in corruption, raised in incorruption! Sown in dishonor, raised in glory! Sown in weakness, raised in power! Sown a natural body, raised a spiritual body! If there is a natural body, there is also a spiritual body... (1 Cor 15:36-44)

The metaphor that Paul uses here is the same one Yeshua used in Essay #2, of our bodies dropping like seeds to the Earth, of them flowering by dying first: Unless a grain of wheat falls to the earth and dies, it remains alone, but if it dies, it produces much fruit... (Jn. 12:24)

Both the seed and the flower which comes of it—which is just the seed itself, transfigured—are solid bodies. Nobody's talking about some empty shell falling on the ground and cracking open, like some escape hatch, so the “real” seed trapped inside can escape to the Mario Brothers’ Mushroom Kingdom beyond the clouds (there are forms of Platonism—and Buddhism—and Christianity—which seem to advocate for that kind of thing, but Paul's religion is not among them, nor is Simeon's—nor is mine).

Rather, the body-as-seed and body-as-flower stand in very real, but mind-surpassing relation to one another. They share, as it were, a perfect physical continuity—the flower comes from the seed, the seed turns into the flower—but, looking at a sunflower seed, for example, never having actually seen a full-grown sunflower before, it would be impossible to imagine something as harmoniously manifold, self-coherent, and serenely beautiful as the flower the seed will become after disintegrating in the ground.

Paul's point here is that Yeshua's resurrection is the dawn of a new creation, planted within the old, in which our human bodies don't just fall apart and become the bodies of other things—trees and flowers and so on—whatever grows on top of our graves—but that they also can become more fully and coherently themselves—i.e., spiritual bodies—which indeed are very solid—much more so, actually:

Sown in corruption, raised in incorruption! Sown in dishonor, raised in glory! Sown in weakness, raised in power!

That is to say: Planted as a body subject to the instability and chaotic jostle of matter as we experience it now through the jostle of our self-addicted minds—and, after death, blossoming as stable and entire!

And also: Planted as something that falls apart over time, leaving us naked and exposed as the forces of nature crash down on us, taking away our beauty and strength, taking away our hair, our teeth, even the ability to hold the reins of our own bowels, until we become helpless self-defecating babies again, but this time dry and brittle—and, after death, blossoming once more with overwhelmingly beautiful human strength and glory!

And here I note that the Hebrew word for “glory,” chabod, refers first of all concretely to something's weight—and then, by extension, to the radiance or beauty it has by being weighty—by being very present and undeniably real; thus Saint Paul's beautiful passage, picked up by C.S. Lewis for the title of his beautiful book:

Therefore we do not lose heart. Though our outward man is decaying, yet our inward man is renewed day by day. For our trouble, light and momentary, is producing for us an eternal weight of glory far beyond all comparison...

The inward man—for Paul, not some vague and sentimental way of talking about one's feelings or attitude, but actually a spiritual body gestating within, which will, God willing, blossom from our body of clay when it perishes, like a radiant and invincible yellow flower in the sun—is, day by day, becoming more real, more alive, insofar as we embrace the suffering of our bodies of dust without losing heart.

In other words, our bodies as we know them now—in Orthodoxy's modification of Platonism—are not empty shells from which to escape, but seeds to be planted in the Earth, so they can grow:

The corollary, then, to the idea that man is a creature who lives through participation in the divine is that inherent in his nature, though it may be only in a dormant state, is the power or faculty through which this participation may be effected: a power or faculty that is as it were a seed or a germ implanted in him at birth, upon whose development depends his growth into the full stature of manhood...

(Philip Sherrard, The Rape of Man and Nature)

And this is also the metaphor that Saint Simeon uses to describe the future transformation of the whole Earth itself and the skies around it, in a passage just before the one that began the essay, and in which he specifically argues against what might have been a natural way to read scripture in his own time of upheaval—as escapist and wistful, as dismissive of the Earth as we know it:

Listen to what the Apostle Peter says: The day of the Lord will come like a thief in the night, in which the heavens shall pass away with a great noise, and the elements shall be dissolved with fervent heat, and the works that are therein shall be burned up (2 Peter 3:10). This does not mean that the heavens and the elements will disappear, but that they will be reordered and renewed...just as our own bodies, which are now dissolved into the elements but still are not turned into nothingness, again are to be renewed through the resurrection—so also the heaven and the Earth with all that is in them, that is, the whole creation, is to be renewed and to be delivered from the bondage of corruption, and these elements together with us will become partakers of the brightness proceeding from the Divine fire....

Just as when our bodies are planted in the Earth, their atoms don’t disappear but only become disorderly beyond recognition—some taken up by the roots of plants, some evaporating into the sky, and so on—so has the whole Earth itself become disorderly, its divine beauty all but hidden in the chaos of its elements—or, rather, in the darkness of our self-obsessed misperception thereof: We should see the brightness of God when we walk around, as easily as we see shafts of pollen-colored sunlight disappear into a riot of azaleas, but we don’t; the wind should be the breath of God to us, touching our inmost breath, but it rarely feels like this, if ever.

And just as the order of our elemental, fragmentary bodies will be restored—and more than just restored, but resurrected—that is to say, they’ll spring forth into a new, radiantly beautiful order transcending entropy—so the Earth will not be annihilated and replaced, but filled with divine life and made to blossom forever.

And then all of its bodies together—tall trees and wild grasses, leaping dolphins and singing whales, stars and planets and sandhill cranes, and, by God's mercy, all of us precious human beings—will shine like flowers in the sunrays of God, as Simeon says:

The heaven will become incomparably more brilliant and bright than it appears now; it will become completely new. The Earth will receive a new, unutterable beauty, being clothed in many-formed, unfading flowers, bright and spiritual...

...which, yes, at times in my life sounded like little more than “visionary lotus-blossoms in the sky,” as Jack Kerouac used to say—just the pipe-dream of a crazy monk, nothing else—but it doesn't at all now, having been in the presence of a monastic myself who's already begun to radiate this new, unutterable beauty from her face—while laughing and rolling boulders—and having begun to feel glimmers of this new life even within my wretched self.

And here's one more, maybe kind of crazy, thing to think about, next to what Saint Simeon is saying about Earth's divine efflorescence in the future.

Sometimes I stay up late listening to recordings of people talk about their near-death experiences (NDEs), for whatever reason. And sometimes I read books in which people recount their NDEs—Raymond Moody's Life Beyond Life, and so on—all the usual suspects—people who have suffered gunshot wounds, for example, and gone into cardiac arrest and suddenly found themselves floating above their own bodies, feeling liberated and euphoric and overwhelmed by cosmic lovingkindness, and, catapulted in their spiritual bodies through tunnels of light, they walk through flowery meadows and talked with Yeshua—I think everyone is familiar with this phenomenon by now, right?

I don't know how many of these firsthand accounts I have listened to or read—a hundred, I'd guess; I love these stories.

And it's striking how many similarities there are between these many accounts, told by very different people, in very different styles, across a wide range of literary skill.

One of the things that comes up again and again is that people talk about their senses as becoming unified and hyperacute, and, reciprocally, experiencing the heavenly Earth as overwhelmingly coherent and hyperreal—the colors, the smells, the tastes, the textures more solid, not less—more vivid, more lucid, more immediately present than anything they had ever experienced before their near-death, or afterward, since their resuscitation—for example, this, from a woman named Sharon, struck by lightning in 2005:

As I stood there in the garden, I noticed once again, how beautiful and brilliant the colors of the flowers, the trees and the grass were. The reds were redder, the pinks more pink, and yellows more yellow. The colors were so much more vibrant than any colors I had ever seen. The air was sweetly fragrant. It was so clean and clear. The grass felt cool to the touch, like on a beautiful spring day. There were birds singing in the trees, and I saw a stream where the water glistened like diamonds in the sun as it flowed over the rocks. I heard music, which was more beautiful than anything I had ever heard before. It was then that I noticed everything had its own pitch or sound. The trees had a sound, the leaves on the trees had their own sound, the grass had a sound, the rocks had their own sound, the water had yet another sound, and so on...It just poured out of every leaf, rock, blade of grass, and every bird. It was the most beautiful sound I have ever heard. I can still hear it, even now, after all these years. It is like a song in the wind. Every now and then, I still hear the heavenly music, as the breeze blows through the leaves on the trees. It carries me back there and I feel that deep, all encompassing love again. It heals my soul and my spirit soars...1

Or this one, from a woman named Nancy, who was hit by a truck while riding her bike in 2014:

A landscape of gently rolling hills surrounded me. Flower-filled grassy meadows spread out on the hills around me. There were huge, deciduous trees in full leaf. The trees were larger and grander than any here on Earth and surrounded the meadows. There was the barest sense of a light mist, as if it were a humid summer morning clung to the tops of the trees. The sky showed a very light blue, similar to what you might see at the ocean's shore, with wispy clouds and a very bright but somewhat diffuse golden light...I felt a deep sense of that love flowing through all things around me: the air, the ground below my feet, the trees, the clouds, and me. I felt the love flowing around me, flowing through me, and eventually capturing me by the heart. I felt supported by a loving Presence so powerful, yet so gentle, that I cried again. I had never experienced such unconditional love and acceptance in all of my years on the planet...2

Well, say what you want about NDEs, I guess—the reptile brain exploding into kaleidoscopic mythopoeia as it loses oxygen, or whatever—but I take them, when I can, as foretastes of Saint Simeon's blossoming Earth to come, with its “new, unutterable beauty, being clothed in many-formed, unfading flowers”—as in, actual flowers waving in actual breezes that you can feel with your face—flowers that we'll smell, as if for the first time, from our actual, very human but exalted mammal noses.

And so here, finally, is how I would say what Simeon said in his passage about the renewal of Earth to come, so we can hear it afresh in our own time of upheaval, when it's tempting to dream of abandoning Earth altogether, or to despair at its implosion:

Thus also the whole cosmos, after it's engulfed in the fire of Divine Love, will be transformed, that there may be fulfilled also the prophecy of David who says that the steadfast shall receive Earth as a gift, after its merciless occupiers have passed away (Ps 36:29)—of course, not the “Earth” as we imagine it now through the dim haze of unreality we walk through like zombies, our sense-perception fragmented, disorderly, all tangled up in addictive, reactive, and manipulated thoughts. For how is it possible that those who have become unified, coherent, clear-eyed, and full of God, will inherit such a fragmentary non-place, which, after all, is mostly just a projection of our own inner rebellion? No, they will receive the Earth again as unimaginably coherent and whole, as unimaginably renewed, and truly alive with the life of God—full of the vivid sights and sounds and smells of Edenic trees and flowers—which they will experience with all of their now truly awakened senses, so as to have firm ground to stand on in their new radiant solidity as human beings—since their old bodies of chaos, planted like seeds, will have blossomed into new bodies blooming far above the anxious jostle that kept everything in their old bodies from ever really feeling real...

And then I would place this passage beside one from Dostoevsky's Brothers Karamazov, which expresses the heart of Orthodoxy, not from the top of some pristine theological tower, but from within the tangled, suffering mess of the world as-it-is:

Love all God’s creation, both the whole and every grain of sand. Love every leaf, every ray of light. Love the animals, love the plants, love each separate thing. If thou love each thing thou wilt perceive the mystery of God in all; and when once thou perceive this, thou wilt thenceforward grow every day to a fuller understanding of it: until thou come at last to love the whole world with a love that will then be all-embracing and universal.

Well, who am I to say—nobody, really—but I think this love for animals, love for plants, love for every grain of sand, for each separate thing on Earth, including our human bodies, as a way of loving the God who loves his whole Earth and everything on it with an all-embracing love, since he made them, will be more pervasive, not less so, in the age to come.

love,

graham

https://www.nderf.org/Experiences/1sharon_m_nde_7925.html

https://www.nderf.org/Experiences/1nancy_r_ndes.html

Truly astounding words. Thank you Graham . It fills me with immense hope. Unhacked Heaven( Paradise ) vs hacked Heaven ( Utopian technocracy ) lies like a fork in the road ahead of us. Is this division of sheep and goats taking place in real time, right now faster than ever? Sounding the alarm with you. Beauty will save the world.

Graham-

Beautiful. You write of things that some of us often sense at times, sometimes very strongly, but fail to enunciate. I know I can get caught up in endlessly dissecting the looming darkness of our times. As if that will save me. Yours is a much needed antidote. Thank you.

-Jack