Some of you may know I'm slowly building our little timber frame home in the forests of northern Minnesota, and have dreams of abundant gardens and orchards there, and of completing its forest chapel, and singing Divine Liturgies in it, and celebrating, like gentle Norse warriors, Agape feasts afterwards on grungy picnic tables among the trees, joined by anyone crazy enough to pray and eat like that with a bunch of equally crazy Christians.

Until that's done and we can move in, we have no home of our own, but live in my wife's parents' basement (thanks Mom and Dad) and dream, and work like hell (which is paradise for me; for the past two weeks, for example, a dear friend and I have been filling the walls in with clay slip-covered straw, a task which leaves me covered head to toe in mud, as a kind of Adam going in reverse, blissfully mindless and all muscle pain...)

And their house is in the suburbs. This is where I write, “famous in my basement,” as John Heers said very much tongue in cheek, in this very enjoyable conversation we had recently.

And it's easy for me, being me, to romanticize the trees and the flowers, and to gainsay the asphalt and the vinyl one also finds in the suburbs, but I do want to take a moment to acknowledge one or two spiritual feelings—familiar feelings, close to my heart, feelings that I love—which come to me from the sad, sad, forever incomplete tower of Babylon we've been trying to build for ourselves, as fallen gods, since practically forever (12,000 years, maybe, according to anthropologists—but scientifically regained memories of life are external, different from the internal memories of the heart, and so 12,000 years ago might as well be forever to us).

I keep wanting to write a poem of American suburbia praising

The totalitarian vinyl siding

Empty of mythological content

But this is not that poem. Rather, it's a poem I wrote a couple days ago, when the late afternoon sunlight and the ticking of someone's air conditioner box and the droning of a single engine aircraft in the sunbleached sky came together to bring forth an old, familiar mood in me—one that I hinted at, in Something In Our Hearts Is Waking Us Up From Self-Erasing Technologies, when I said:

I'll admit, though, that there is an allure to the melancholic emptiness of spaces in which intelligence has outstripped life. As a kid, I could spend hours in disembodied, machine-articulated worlds with absolutely no one else in them—like Riven, the sequel to the computer game Myst...

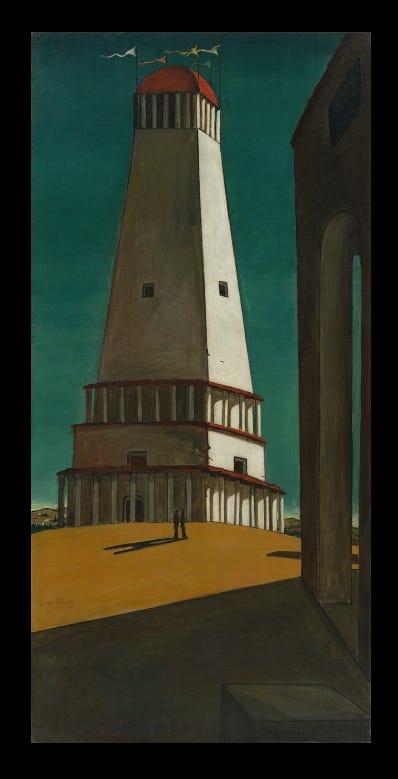

It's the same mood which comes to me from Nostalgia of the Infinite, by Giorgio di Chirico, an example of what he called, “Metaphysical Painting,” which I see now as a kind of Cartesian iconography, a two dimensional dream of the left mind lost in itself, self-existent in an existence devoid of the life brought forward by communion with other minds:

And also the same melancholic vastness of “Live Forever,” a song by Moby which I love, and which I listened to again and again as I wrote the poem, and which I'm listening to now:

I encourage you to listen to it, as you read the poem below, against the backdrop of having seen Nostalgia of the Infinite, too—a small poem, but, I hope, also a full one: